The other day I had what seems like a fairly obvious idea in hindsight: an inversion of the famous Maslow Hierarchy of Needs. A quick internet search reveals that this idea has occurred to others although I didn’t find a version that fits the way I was thinking about it.

My idea was that the Maslow hierarchy needed a Jungian shadow or inverted segment. I was pondering this in relation to Kierkegaard’s idea that “the door to happiness opens outward”. That is, you cannot “push” your way to happiness. You cannot read Maslow’s hierarchy and try to follow the steps. (Disclaimer: I haven’t actually read Maslow, so I may be doing his ideas an injustice here).

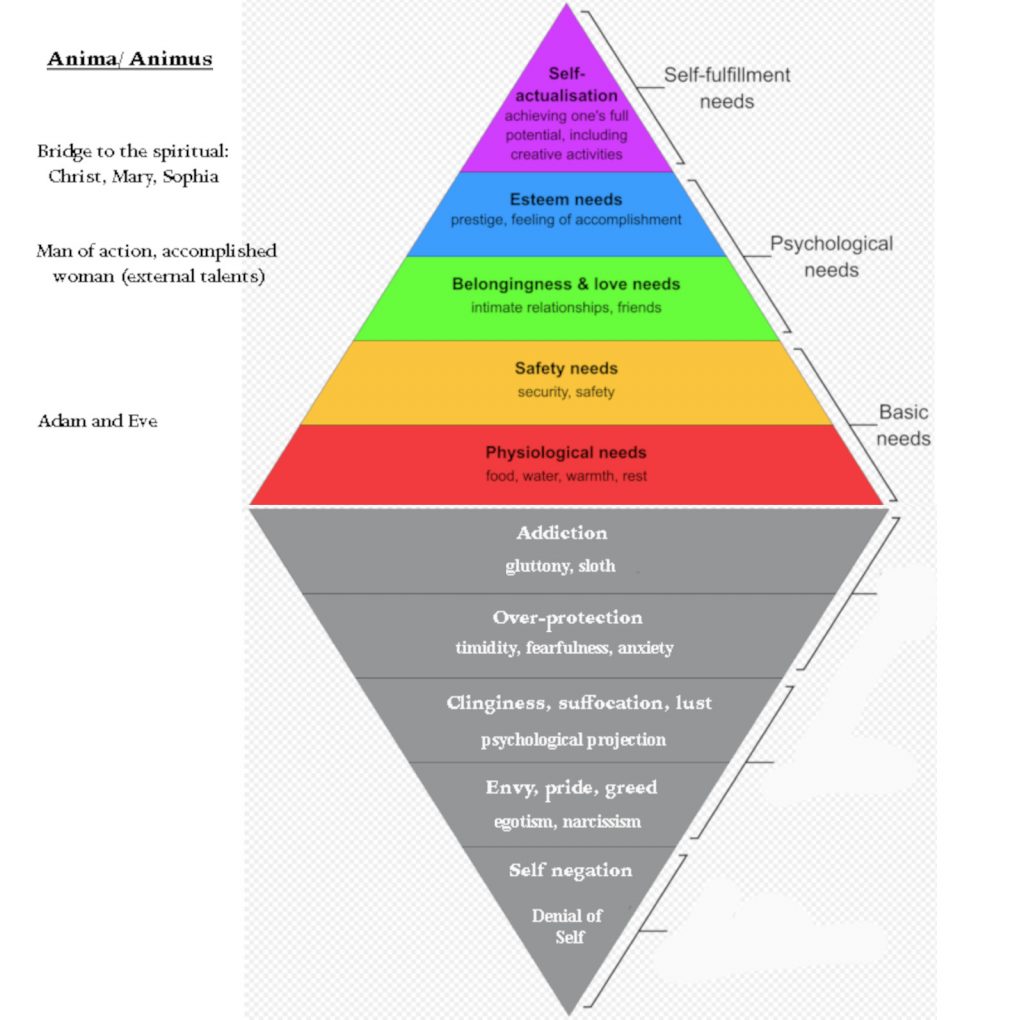

Anyway, here is my version of the Maslow hierarchy with a Jungian shadow below mirroring the pyramid that everybody will be familiar with. It seemed fitting to draw it in doomy grey.

The idea is that the inverted segments below the mid-line are the “shadow” side of the positive segments that we all know. Thus, the shadow of Physiological Needs is Addiction. The shadow of Safety Needs is Fear. The shadow of the need for Belonging and Love is Clinginess and the projection of your own insecurities onto the other person. The shadow form of Esteem is Egotism and Narcissism. Finally, the shadow form of Self-actualisation is the denial of Self. Ultimately, all the shadow forms are an attachment to the ego which prevents the transcendence to the Jungian Self.

I also mapped Jung’s anima/animus progression on the left as this matches to Maslow’s concept in the sense that Jung believed one progresses through the different levels. The basic physiological needs Jung considered to be the base level anima/animus as represented archetypally by Adam and Eve. Belongingness, love and esteem maps to the second tier anima/animus as the man of action or accomplished woman. This is the person who has found a place in society where they feel they belong.

Jung had two extra tiers of anima/animus that map to the Self-Actualisation phase of Maslow and this is where things get interesting because Jung’s individuation concept seems to imply that you have to first manifest the shadow forms in order to get to individuation. In other words, Maslow was missing half the story because he implies that you can “ascend” the hierarchy in a purely “positive” fashion whereas Jung believed you have to first descend down to “hell”. You have to manifest the shadow before you can integrate it.

Kierkegaard had a similar idea. He would have called the “self negation” tab at the bottom of the hierarchy “despair” and he implied that one could not self-actualise without first going through despair. This fits with Jung’s concept of enantiodromia. There is a sudden reversal from despair to self-actualisation/individuation but it is not something you can plan for. The door to self-actualisation/individuation must open for you, you cannot push it open.

Just as despair has many forms, so too does the positive side of the equation and thus the last two anima/animus steps to go from Maslow’s esteem needs to self-actualisation. Thus, in relation to the anima, Mary is the 3rd tier and Sophia the top. Both of these would be sub-levels within Maslow’s self-actualisation phase. The poet, Robert Graves, had a similar idea although he a triad of anima figures with Mary, the White Goddess and the Black Goddess as Sophia. This is probably where the correspondence with Maslow breaks down since it doesn’t feel right to call these “potential”.

That’s why so many famous religious figures were actually successful people in earlier life but renounced their success to pursue something higher. It may very well be that you need to renounce all the other needs in order to pursue Self-Actualisation at all; hence poverty, celibacy and living away from society. Whether that renunciation is the equivalent of manifesting the shadow forms in a Jungian sense is an interesting question. I think Kierkegaard would have said one needs to be a sinner first. Avoiding sin altogether is also avoiding despair.

Both Jung and Kierkegaard believed that most people will avoid despair. Within this model, that would prevent them from attaining self-actualisation. Because we live in a time where physiological needs are taken care of, this would mean that we would expect most people to get stuck at egotism and narcissism, unwilling (or perhaps uninvited is a better word) to take the final leap into despair necessary to transcend the ego and integrate the Self. Sounds like a pretty good description of modern society to me.

Hi Simon,

Flipping Maslow’s hierarchy on its head is a great idea. It always seemed to be a bit far-fetched that the original pyramid claimed we as a species were moving in a particular direction. And it seemed like an even bigger claim to suggest that as an end-goal. It may not be reached, and who knows, there may be other destinations equally as valid? I have this odd hunch that Maslow may have been heavily influenced by the ideals of his middle to later years and sought to guide civilisation in a particular direction.

I must add that the inclusion of the Jungian shadow perspective fits the messiness of reality far better. And I agree with your analysis in the concluding paragraph.

Cheers

Chris

Chris – I believe Maslow didn’t come up with the pyramid picture so it may be that the way his ideas have been represented in popular culture is not what he said. Wouldn’t be the first time.

Funnily enough, adding the Jungian shadow idea is pretty much just a repetition of the 7 Deadly Sins. I think religion was onto a similar idea: first avoid sin (do no evil) then worry about doing something “good”.

This one doesn’t seem to have gotten the commentary response that your Corona posts usedta. I think the pandemic caused more of an emotional response — fear is a strong motivator! — which energised people to enunciate in the comment section.

Interesting concept, the anti-pyramid. I wish I had seen this when I still had a job. There are several psychologists at various community mental health offices I could have shown it to for discussions. Our community teams had open-plan seating with nurses, social workers, psychologists, some of the lower-level psychiatrists and others all within earshot. Psychologists (not all of ‘em, but many) tend to be more open to chatting about concepts, whereas nurses don’t have as much curiosity, being more task-oriented. “Did they swallow that tablet? Is it the correct dose of the ordered medication in the syringe I’m about to jab them with? Can’t talk — I’ve gotta write a progress note in the computer system about what I just did.” And psychiatrists are operating at a different level, mostly focused on pharmaceuticals and neurotransmitters. They already know everything (so they think) and they’re too busy to natter about the philosophy of being a happy human.

Maslow has always been in the back of my mind since I was exposed to the self-actualisation model during Psychology 101 in my first go-round at uni, and decades later got it drilled into me when I was in nursing school. When I’d be thinking “what does this patient need in order to stay alive?” Maslow provided a good frame. For the medical patients when I was a hospital floor nurse, it was “can they breathe? Are they dehydrated? Are they able to eat?” That might seem simplistic, but when someone has emphysema from a lifetime of ciggies, or they’ve had a stroke that wiped out the part of their brain that controls one side of their body so they can’t swallow properly and choke when liquid trickles into their lungs instead of their stomach, they have a hard time covering Maslow’s base.

When I got into the psych side of things full-time, I could contemplate how a person’s presentation fit in with some of the higher levels of Maslow. They’re depressed and have made two suicide attempts by overdosing on their meds. Socially isolated, estranged from their family, struggling economically — not getting to Level 3 and 4 on the pyramid. Not that Maslow considerations are an official part of the psychiatric team’s analysis. He’s not mentioned outside of uni, and there is apparently an anti-Maslow school of thought, according to a couple of brief comments I got from psychologists when I named-checked Maslow over the years. I never bothered to delve into that because Maslow is almost as irrelevant to the day-to-day psychiatric milieu as Freud.

BTW, I’m reading a book titled “Desperate Remedies” that touches on your man Jung.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2022/06/03/psychiatrys-brutal-history-unanswered-questions/

It’s a warts-n-all history (mostly about the warts) of psychiatry since the 1800s. My daughter posted it down as a birthday present this year. Wow! has there ever been some atrocity done to poor suffering bastards because it was “the science” of the day. Your uber-scepticism would mesh with the book’s look at things. The psych scene is more humane now than the U.S. in the 1920s, when they routinely yanked out the teeth of psych patients because “the science” said infected chompers produced bacterial toxins which poisoned the brain and caused mental illness. (Fun fact — the only two Nobel Prizes in Medicine that were awarded for psychiatric discoveries came for techniques that would today result criminal charges — lobotomies and injecting patients with malaria-tainted blood in order to cure schizophrenia. Things I never knew before reading that book from my kid.) But I bet that in the future, assuming there IS one, our total reliance on “give ‘em a dopamine blocker! Up the dosage of the mood stabiliser!” is going to be looked at as being primitive like the old insistence on massive enemas to flush the colon in order to cure schizophrenia. The doctors then “knew” that constipation caused hallucinations…

Anyway, ol’ Carl makes an appearance when he travelled to America with Dr. Siggy in the early 1920s. They were frenemies at the time, in search of the Big Yankee Dollars, coz there wasn’t much money in what was left of the Austro-Hungarian Empire post-WW I. German wisdom had the same cachet as German cars have now, before ‘dolf and the Nahtsees trashed the brand name. Jung doesn’t get much coverage in this book, which spent a lot more words on Freud’s “talking cure” approach, since that took over the American mindset for generations. Someday I’ll haveta chat to you about how I got labeled as having an Oedipus Complex by a Freudian shrink when I got tossed into a mental hospital after running away from home at age 15. Oh yeah, I’ve been on the wrong side of Sigmund…

Bukko – I hear ya. Anybody familiar with the history of medicine ought to be a lot more skeptical of “trusting the science” especially when the science is some new whizzbang thing that’s never been tried before. Oh, yeah, and not bothering to test whether the whizzbang thing actually does what you claim it does, all part of the job description. I think I’ve mentioned before that there’s a history of schizophrenia in my family. Let’s just say I’m quite lucky to be here given the kinds of treatments that used to get dished out.