Several months ago, when there was a mini-panic in the middle of winter with threats of electricity blackouts in eastern Australia, I wrote a couple of posts on the Australian electricity market (this and this). The blackout threats are something I have been expecting for some time as Australia has continued to add intermittent power sources (solar and wind) to the electricity grid. Not surprisingly, they came in winter when the days are short and the sun has a nasty habit of hiding itself behind clouds instead of shining on solar panels.

In the end, there were no widescale blackouts, but the Australian energy bureaucracy’s own guidance is that blackouts will become a problem perhaps as early as 2025. That will be a problem for the future. Right now, the political problem is price as the retail price of electricity continues to rise in Australia as in most other countries. This political pressure has triggered what might just be a paradigm shift in Australian politics, so I thought I would take a post to sketch out what that might look like.

The question about whether renewable energy is cheaper than other forms of energy generation is one of those topics that arouses heated debate. I don’t claim to know for sure what the answer is and the reason is because electricity generation is, in the language of the old school systems thinking that I like to use to analyse such problems, a medium number system. Medium number systems display organised complexity and can be distinguished from the organised simplicity of systems like Newtonian planetary physics and unorganised complexity eg. behaviour of gas in a container.

When trying to understand medium number systems, our culture loves to create models. Whenever you see a headline “experts say…” or “studies have shown….” that means somebody constructed a model. The problem with modelling medium number systems is that you can’t reduce the variables enough to get calculable, reliable results. Therefore, any model you create, even if it seems to correlate to empirical data over some time period, can be wrong (in fact, will be wrong, but might be useful).

Some argue that it’s still better to create the model. Maybe. But a model can give you a false sense of security and certainty. The approach I prefer is the heuristic-based approach where you apply many different heuristics to the problem knowing that they are fallible but trusting that the combination of perspectives can give insight into what is going on. This approach requires a level of humility that doesn’t gel well with our culture. We prefer to be certainly and heroically wrong than just a little bit more right than wrong.

When trying to understand the medium number system that is the Australian electricity market, one of the heuristics to use is the history heuristic. That’s the approach I took in the first of my posts some months ago.

The ultra-short version of that history is this: Australia built a large grid in the post war years that ran almost entirely on coal. Because Australia has huge, economically extractable coal reserves, we enjoyed almost the cheapest electricity in the western world up until the early 90s. Then we jumped on board the neoliberal agenda which required the privatisation of the electricity grid. We were told this would reduce prices through the wonders of the free market. Starting in the mid-2000s, we began adding solar and wind generation at scale. We were told this would reduce prices as renewables were now the cheapest form of electricity generation.

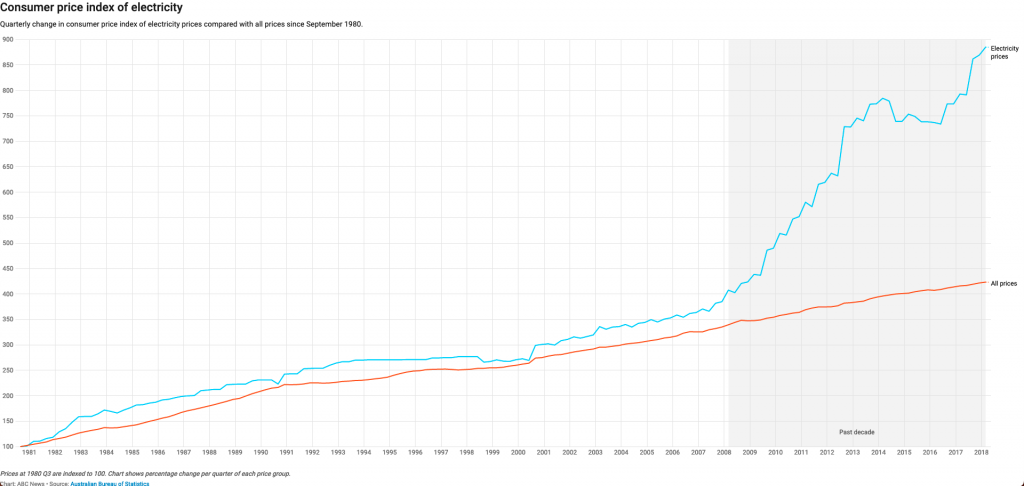

Either way, the price should have gone down. That’s what we were told. Here’s what actually happened.

What has gone wrong? There are two main suspects under investigation.

First hypothesis: Crooked capitalists are screwing over the public like they always do. The privatisation in the early 90s is the cause of the price rise.

Second hypothesis: Renewables are not really as cheap as we’re told. The increase in solar and wind generating sources has driven the price increases.

It’s possible to create models to justify either of these hypotheses. There has definitely been gold plating of the transmission system and weird behaviour from electricity retailers which lends support to hypothesis 1. On the other hand, the enormous spending on extra transmission lines in recent years was necessary in order to hook remote solar and wind generation into the grid. This would be evidence for evidence for hypothesis 2.

From a systems theory point of view, both the privatisation of the grid and the renewable energy push of the 2000s have one thing in common: they have made the system far more complex. When we’re talking about whole systems, complexity comes at a cost. Without knowing any of the underlying details, we can surmise that a system that is more complex is less efficient. To get the same output, you’ll need to increase the input (of energy and $$).

The privatisation of the system in the mid 90s added complexity to the organisational structure of the system. Up until 1990, the electricity system here in Victoria was a single entity known as the SEC. This entity handled everything about the system including generation and retail. The privatisation reforms got rid of the SEC and split the system into four separate sectors: generation, transmission (high voltage), distribution (low voltage), retail.

Complexity always comes at a cost. In relation to organisational complexity, one of those costs is regulation. Private enterprises that run for profit are going to maximise their profit and will be tempted to do so at the expense of the common good. All of history teaches us that. If you introduce more profit seeking players into a system, there is going to be more chance for corruption. To combat that, you’ll need to spend more money on regulation (bureaucratic departments, lawyer fees, court resources). That’s one extra cost.

Another extra cost is the communication overhead. More nodes in the system means more points where communication can break down. This can be mitigated by introducing information technologies. But software comes with its own complexities. More importantly, software is expensive. It is an extra cost that you now need to pay to run a more complex system.

The addition of renewables since the mid-2000s has also added significant complexity to the system. Rather than a few enormous coal fired power stations, you now have a solar farm here, a wind farm there, a hydro over there, an Elon Musk battery over there. You’ve got numerous small-scale sources providing highly variable amounts of energy. That variability needs to be balanced out to keep the grid up. What happens when that doesn’t happen? You get blackouts. And then you get court cases and fines. In other words, more cost. (On a positive note, it does keep a few hungry lawyers off the streets).

This has only worked so far because of the massive redundancy built into the original grid. But at some point it will no longer work and that’s why the energy bureaucracy is already predicting increased blackout risk. Think of it like a diesel car. You can add a certain amount of gasoline to the fuel mix and the car will still run. If you keep increasing the gasoline in the mix, however, eventually the car will breakdown. The car was not designed to run on gasoline and our electricity grid was not designed to run on renewables.

So, I would expect that both privatisation and renewables have caused the price of electricity to go up. The difference is that all the cost from privatisation should already be baked into the system while the cost of extra renewables (the complexity cost) is increasing as more renewables get added to the system.

Well, it looks like we may actually get a clearer picture which of the two hypotheses is correct because the price increases have now created enough political pressure that there has been a big development in energy policy in Australia in recent months. In both NSW and Victoria, Australia’s two most populous states, the left-wing Labor parties have begun using rhetoric that explicitly blames privatisation for the cost spikes in electricity. Here in Victoria, the government announced a plan to directly fund generation and even get a government-owned SEC back into the retail game.

This is pretty big news. The privatisation agenda was a core plank of neoliberalism. If this rhetoric turns into reality, this starts to look like the official end of neoliberalism in Australia.

Of course, for now the measures are small and the choice of rhetoric looks opportunistic. Greedy capitalists always make a useful scapegoat and politicians desperately need a scapegoat given that they have been caught with their pants down now that the electricity price refuses to do what they promise. It’s also true that the whole renewables push is a core component of the Save the Planet™ ideology which won Labor the last election. The choice between blaming capitalists or blaming renewables and undermining that ideology is a politically obvious one.

What is interesting from an Australian political point of view is that this new rhetoric gives the Labor Party a way to ideologically service its core demographic of inner city intelligentsia/bleeding hearts while also capturing the demographic which is currently up-for-grabs: the outer suburban working class. Labor can promise it has a plan to cut prices, which will appeal to the working class, while also Saving the Planet™ which is the main concern of the inner city types.

By contrast, the Liberal-National coalition looks set to try and jump on board the nuclear bandwagon. I don’t expect that will be a winning strategy. Thus, Labor might accidentally find a way to become a populist party in the years ahead and they’ll do so by returning to their roots of bashing capitalists.

This fits my broader prediction that Australia will revert to our social democracy roots as things get tough in the next decades. Neoliberalism was always a bad fit here. It was only really adopted to appease the bankers who run the US empire. As the US empire continues to decline in the years ahead, Australia should get more leeway to choose its own path and I expect we’ll revert back to what once worked.

Ultimately, none of this will solve the electricity price problem, however. The only thing that will bring prices down is to reduce complexity in the system. A full return to government control would do that. One way it might play out is that a crisis of some kind, almost certainly large scale blackouts, could see governments, who would already own a substantial part of the system by then, buy out the remaining private players and the whole thing will revert to government control.

If hypothesis 2 is right (as I suspect it is), the price will still not come down because of the fundamentally complex nature of renewables and the associated complexity tax they impose on the system. At some point, possibly a few decades from now but maybe as early as the end of this decade depending on how things play out, a decision will have to be made whether Australia wants to have a permanent 24/7 electricity supply or whether we want to continue the renewable dream.

If we choose the former, there are still enormous coal reserves at our disposal conveniently located right next to existing transmission lines. Will government fund the construction of new coal plants? It would not surprise me in the slightest. And Save the Planet™ will go up in a puff of coal-powered smoke.