There was one aspect of the movie that was the subject of last week’s post, Kurosawa’s Sanjuro, that I think it is useful to spend more time going over and that is the relationship between Intellect and Will. Kurosawa places this distinction at the heart of the plot of Sanjuro since the group of naïve young aristocrats who are on the verge of getting themselves killed at the start of the movie are exercising their Intellect but not their Will. Meanwhile, the wily Samurai who will save them is operating from Will. What Kurosawa makes clear time and again throughout the movie is that Will trumps Intellect in “the real world”.

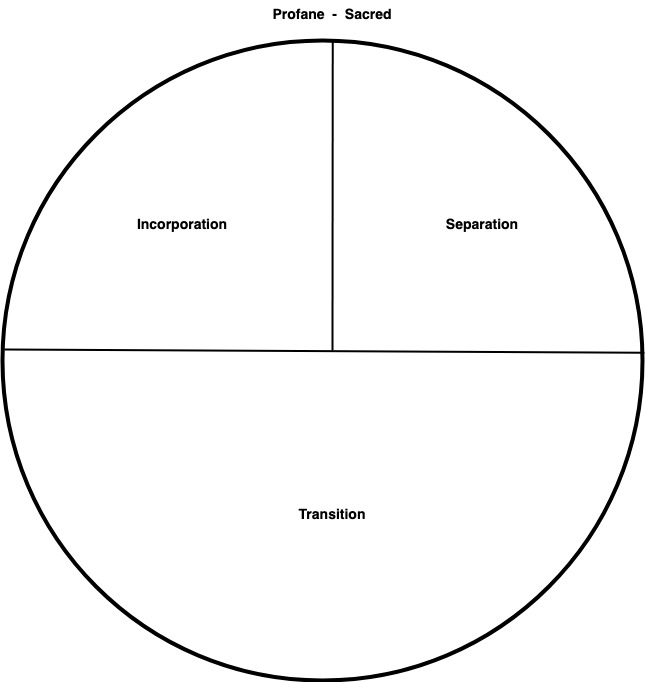

In my archetypal table, I assign Intellect to the Orphan phase of life and Will to the Adult phase as follows:-

| Physical | Exoteric | Esoteric | |

| Child | Pre-puberty | N/A | Imagination |

| Orphan | Puberty | Student, apprentice | Intellect |

| Adult | Maturity | Economic, political, sexual maturity | Will |

| Elder | Old Age (menopause) | Mentor, Elder, (Retired) | Soul |

The young aristocrats are Orphans because they have no official responsibilities in the clan. That is why they must petition the clan leader to get something done. They have correctly used their Intellect to figure out that there is corruption going on. What they don’t realise is that knowing something to be true is a very different thing from proving it and a different thing again from ensuring justice gets served.

Even in the modern world with our egalitarian ethic and the nominally equal access that everybody has to the courts, there is incredible naivete around how the justice system works. The justice system does not guarantee justice. It only guarantees the chance at justice. The pursuit of justice belongs more to the realm Will than to the Intellect. Going through a court case takes time, energy and especially money. Knowing something is true intellectually is a different thing to standing in court and asserting that truth, especially since others will stand and assert that you are wrong. In short, the pursuit of justice rests far more on Will than Intellect. The young aristocrats begin the movie with the mindset that many naïve people still have in our time that just because they are right means that justice will be served.

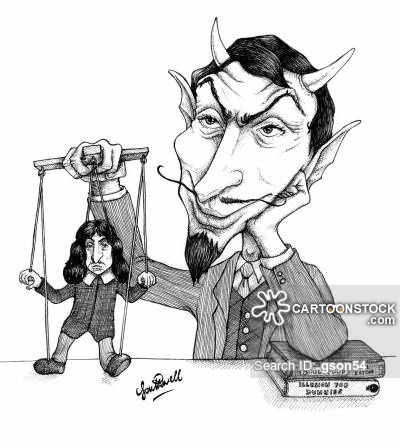

But the naivete of the aristocrats goes deeper than that. The Intellect, when used in the absence of other faculties, operates much like a modern computer and, just like modern computers, the principle of Garbage In, Garbage Out holds. People operating purely by Intellect are easily deceived. All you have to do is control the input they are operating from and then you control the output, the conclusions that they will draw.

Throughout Kurosawa’s movie, various traps and deceptions are laid by the bad guys, the superintendent and his accomplices. Their goal is to lure their opponents into situations where they can either frame them for made up crimes or just kill them outright. The naïve aristocrats fall for the bait every single time and it is only because they have samurai to help them that they escape.

What does the samurai have that they do not? We could sum it up in a word whose modern meaning has taken on a negative connotation, cunning. In Old English, the word cunning used to mean simply “to know”. It was one of a pair of words that most other European languages have but which has disappeared in modern English. In modern German, there is still the difference between kennen and wissen. Cunning comes from the same root word as German kennen.

Although the semantic difference is not clean, the difference between wissen and kennen is that between abstract knowledge and practical knowledge. What I am calling Intellect is about abstract knowledge and therefore maps to German wissen. Kennen, and English cunning, are about practical knowledge. Because practical knowledge comes from lived experience, and because lived experience is based more on Will than on Intellect, cunning is the kind of knowledge that comes from Will-fully acting in the world.

Part of Will-fully acting in the world is coming to understand that the world does not run on Intellect and its abstractions. Many a philosopher throughout history has come to the conclusion that the world should run on Intellect and the way to do that is precisely to remove the element of Will from the equation. It’s a nice idea, but, as the movie Sanjuro shows, it can get you killed, especially in the domain of politics. To operate in the real world, you need cunning. That is what the naïve aristocrats completely lack.

But, the distinction between Will and Intellect, cunning and knowing, holds even outside of political gamesmanship.

The consequences of any enterprise of reasonable complexity cannot be calculated in advance. To refuse to act until you have attempted to calculate all possible effects leads to analysis paralysis. This is before we even get into the various paradoxes of Intellect which call into question the possibility that Intellect can generate valid outputs in the first place.

The question of determinism has been around for millennia, but the late 19th century saw a particularly strong form of determinism take shape fuelled by the enthusiasm surrounding the progress of science. It was genuinely believed by certain thinkers and scientists that the Intellect would soon solve all problems and we could know pretty much everything there was to know. We could then predict the outcome of any action with complete certainly. Put into our terminology, it was the belief in the infinite power of the Intellect. Of course, it fell apart in multiple ways including from within the scientific paradigm itself.

We can frame the problem in the terms of system theory by simply saying that action in the real world requires dealing with irreducible complexity and therefore the results cannot be calculated in advance. To act knowing that the consequences cannot be known in advance requires the use of Will. It follows that action according to Will requires an understanding of the limits of Intellect.

But it’s also true that orientation to the world based on Will is different from orientation based on Intellect. The Greek philosophers like Aristotle were at least consistent since they explicitly eschewed worldly action. Sitting on a mountain and using their Intellect was what they considered to be the highest attainment for a human being. It was how we could get closest to God. Their god was a god of Intellect and not of Will.

Part of the reason why Kurosawa’s Sanjuro is such a great movie is because it makes clear what is the difference between acting in the world according to Intellect and according to Will. The samurai and the bad guys are acting according to Will. The naïve young aristocrats are acting according to Intellect. What does this mean in practice?

Well, one of the main differences is that both the samurai and his opponents are inherently distrustful of information. More precisely, they judge information only once they know its source. There’s a great scene towards the end of the movie where Sanjuro is attempting to lure the troops of the superintendent to a specific location. When the fake news is reported to the superintendent, his first question is “who is this samurai?” He doesn’t take the information on face value. He wants to know who is providing it. He wants to know the intention, the Will, behind the information.

By contrast, time and again, the naïve aristocrats take whatever they hear at face value as if it’s the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. They have no concept of Will and therefore no concept of deception. The idea of deception might sound obvious to those of us who live in the real world where lies are commonplace, but for cloistered aristocrats who live in ivory towers, it can be a real shock.

It was also a central problem in the philosophy of Descartes. Descartes introduces it via the concept of the evil demon which is essentially a question of how the Intellect can know it’s not being deceived. Descartes wanted to create a system where the Intellect could be sovereign and not have to rely on the other faculties.

Some philosophers and theologians have gotten around the problem of the potential corruption of the Intellect by stating that the world we live in is inherently corrupt and we should not expect to find truth here at all. Maybe they’re right. But there is another strand of thought in modern Western culture which has explored the idea that maybe Will is more fundamental than Intellect (Schopenhauer, Nietzsche and others).

In his own way, Kurosawa also explores this idea in the attitude that the aristocrats have towards the samurai. There’s a scene where one of them calls the samurai a “monster”. Another says that he can’t be trusted. This happens quite late in the movie after the samurai has saved their lives several times. How could the aristocrats fail to trust a man who has saved their lives repeatedly?

The reason is because they do not understand him and, for the aristocrats, Intellect is everything. They can only trust what they understand. Compare this to ancient Greece and Rome. Before any major decision, the Greeks and Romans would consult various oracles. The oracles were not there to predict the outcome of a course of action. Rather, they were there to ascertain the Will of the gods. The Greeks and Romans would consult whichever god was seen to have authority over whatever it is they were doing, be it planting a crop or going to war.

Whatever else you want to say about this, one of the effects of such a practice is to take decision making out of the hands of Intellect and place it in the domain of Will. Reading oracles is an inherently irrational process. It meant that the decision could not be judged by Intellect.

Why would you want a decision not to be judged by Intellect? Because of our aforementioned point: the consequences of any enterprise of complexity cannot be known in advance. But that doesn’t stop the Intellect from judging those consequences after the fact. One of the ways this manifests is in the phenomenon of preachers thundering away in pulpits about how everything that goes wrong in the world is evidence that God is punishing us. We see the exact same thing in the modern world where various ideologues will judge actions after the fact with the implication that if we only followed their ideology none of it would have happened.

All this is born out of the same error of not understanding the limits to Intellect. Does the preacher or ideologue have a broadband connection directly to the central server of heaven? Do they know (Intellectually) what God knows? If so, why didn’t they enlighten us all before the action rather than wait for the consequences to manifest? The reason is because they couldn’t have known in advance. All they can do is judge after the fact. But this is an invalid use of Intellect and the result is fake knowledge. Of course, this problem is not limited to preachers and ideologues. We all have a tendency to fall into this trap through the misuse of Intellect.

One could argue that the ancients took the idea of Will too far and ended up in the realm of fatalism where life was just a long process of being thrown this way and that by the Will of the gods and all you could do was accept it. This explains the extreme stagnation that set in during the Roman Empire where scarcely any attempt was made to change things for the better. Why bother when it was just the Will of the gods? The same was true for Egypt and, seemingly, for most civilisations of that era.

Kurosawa’s movie shows us a more mundane version of the same dynamic. It is about how those who operate according to Intellect alone (the aristocrats) misjudge those who operate according to Will (the samurai).

But the reverse is also true. The samurai must learn how to deal with the aristocrats. He is used to operating by Will alone and not having to worry about making his Will comprehensible by others. That’s part of the reason the aristocrats don’t trust him. He doesn’t explain his strategy to them in terms they can understand. Eventually, at the end of the film, he figures it out. How does he solve the problem? By giving them explicit, binary instructions. When this, do that. Otherwise, do nothing. Finally, they are able to follow along and his plan comes to fruition.

The moral of the story is that those who would lead must translate their Will into terms their followers, using Intellect, can understand. Here we have the origins of bureaucracy. A bureaucracy is an organisational structure that runs on rules like a machine. Since the Intellect is good at comprehending rules, a bureaucracy is the natural place for people like the aristocrats in Sanjuro.

It is noteworthy in this respect that bureaucracy was created in Asia while the ancient Greeks and Romans had almost no bureaucracy until very late in the Roman Empire, and even then only a minimal one. The ancients had solved the same problem in a different way. Consulting the oracle was a way to take the matter completely out of the hands of Intellect and therefore get alignment based on a shared agreement to the “Will of the gods”.

In our times, we see both of these “solutions” present. On the one hand, we have an enormous bureaucracy. But it’s one of the ironies of our time that “science” has largely come to take the place of the oracles used by the ancients. Since the average person assumes in advance that they cannot understand science, Intellect is removed from the equation. The pronouncements of modern science have thus become equivalent to the pronouncements of the ancient oracles and, as the corona debacle showed, they are often just as irrational.