Everything that I’ve written in the last few posts is broadly compatible with the analysis of Spengler in Decline of the West, and so it’s probably worth spending a post on the comparisons between my analysis and his, since this will also allow me to present what I think is my final answer to a puzzle that I’ve been trying to sort through for more than a year. The puzzle relates to Spengler’s concept of pseudomorphosis.

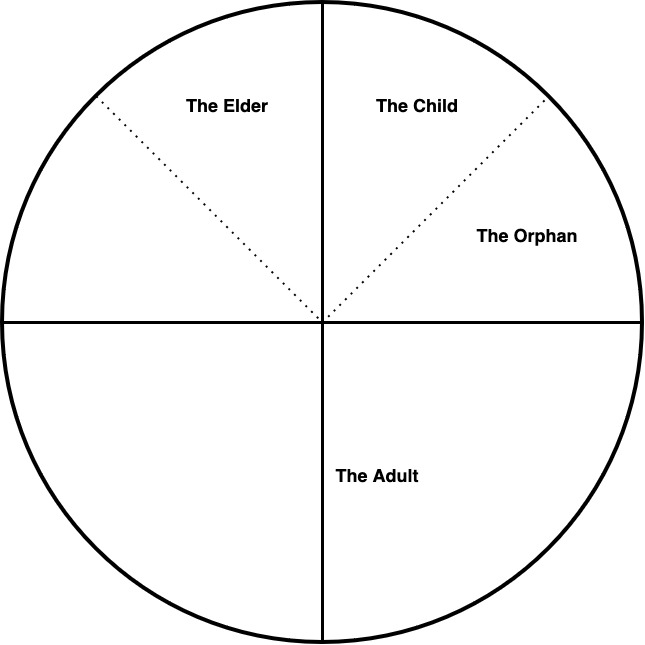

To describe pseudomorphosis, I like to use my levels of being concept. Mostly, I’ve been using a three-part distinction between Physical, Exoteric and Esoteric, but since we’re talking about Spengler, it’s useful to further divide the Esoteric into upper and lower. While we’re dividing, I’ll also divide the Physical into alive and inanimate. Here’s how that looks:-

| Level of Being | Scientific domain |

| Physical – inanimate | Physics, chemistry |

| Physical – alive | Biology |

| Exoteric | Sociology, politics, anthropology |

| Esoteric – lower | Psychology |

| Esoteric – upper | Theology, philosophy |

The Exoteric level of being includes all the outward forms of a society, including the political, economic, and religious institutions as well as cultural practices embodied in symbolic form in rites of passage. A wedding ceremony, for example, has an Exoteric form in the ceremonial actions carried out by the various actors, the special clothing, the sacred location (e.g. Church building) etc. A wedding ceremony also resonates at the Esoteric level. It gets its meaning at the highest level of the Esoteric, while also having a psychological resonance in all of the emotions, excitements, and dramas that accompany the event. In real life, of course, we experience the levels of being simultaneously and don’t differentiate between them.

It is because Spengler speaks in the high falutin’ language of German romanticism that reading him can make us lose sight of the fact that these concepts belong to everyday life in society. Nevertheless, it is true that Spengler is mostly concerned with what we have defined as the upper Esoteric, which are the core concepts that unify a culture and which, almost by definition, require an extensive education to come to grips with. Therefore, they are usually understood in the fullest terms only by a small minority. An educated priest should be able to explain how the layout of the church maps to the concepts of Christian theology, but two people getting married in a church don’t need to know any of that Esoteric stuff. They simply need to perform their prescribed Exoteric roles.

The assumption is that it is the Esoteric level of being that determines the Exoteric, and this is the main reason why I prefer these abstract names. Esoteric simply means “hidden”, while Exoteric means “visible”. By calling it the Esoteric, we abstract away from theological and philosophical debates and avoid getting bogged down in metaphysics. As a result, the term Esoteric works equally well whether we think the highest meanings of our lives come from God or whether, like Spengler, we assume they come from some kind of cultural instinct derived from geography.

Now that we know the difference between the Esoteric and Exoteric in broad terms, we are ready to understand the concept of pseudomorphosis, which is one way in which the two levels of being get out of alignment. Since Spengler was concerned with entire societies, that’s where his focus lies but, again, we should note that this is a very common occurrence in our own lives. Ever had a job that you used to like but then got bored with? That means your Esoteric level of being (emotions, goals, desires) no longer matched your Exoteric level of being (the job). The same can happen in marriage or romantic relationships, in church, in your political affiliation or even in banal things like what you normally eat for breakfast. Life is the process of trying to find an equilibrium between the Esoteric and Exoteric levels of being so that the outward expressions of our lives match the inner.

Sometimes, the equilibrium between Esoteric and Exoteric is thrown out of balance by factors external to us. That can also happen at the societal level. It is the latter which Spengler was concerned with when he talks about pseudomorphosis. Specifically, he was referring to a general pattern that occurs where the Exoteric institutions of a dominant society are imposed on a subordinate one. Implied in his definition is that we are talking about a situation where one culture is defeated militarily and is now under the domination of another. A classic example from our time would be the nations conquered by the United States, which then had parliamentary democracies installed in them. Parliamentary democracy is an Exoteric institution born in western Europe and is, therefore, not “native” to those nations.

What happens in pseudomorphosis is that the Esoteric spirit of the subordinate culture finds itself mismatched with the Exoteric forms that have been imposed on it. Spengler assumes that this will give rise to the emotion of hatred on the part of the subjugated people, who will come to despise the culture that dominates it. For Spengler, this hatred is not just born out of the obvious resentment that comes from military defeat but is inherent in the mismatch between the Esoteric and Exoteric.

The issue I have been puzzling over in relation to the concept of pseudomorphosis is that it seemed certain to me that Faustian (modern European) civilisation was itself born out of a pseudomorphosis of the Classical civilisation (ancient Greece and Rome) in that it was created from the Exoteric institution of the Catholic Church, which was itself the product of the Classical civilisation. The problem was that there was no emotion of hatred involved and also no implied real-time political and military domination since the Classical civilisation had ceased to exist by that time. Since Spengler had defined pseudomorphosis to require both of these properties, it didn’t strictly fit his definition, but, if we allow the definition to be expanded, we can account for two phenomena that Spengler and many other thinkers have puzzled over for centuries and which are crucial to understanding Faustian civilisation.

The first is what happened in the late Roman Empire. In one sense, this was a classic pseudomorphosis in exactly the way that Spengler defined it with the Classical civilisation being the dominant one and the Magian (located mostly in what we would now call the Middle East) being the subordinate. We all know this story intimately since it’s the civilisational background of the New Testament. Moreover, we even see exactly the forms of hatred and resentment that Spengler talked about, for example, in the various Jewish revolts against the Romans. We can represent that pseudomorphosis in table form as follows:-

| Level of Being | Classical | Magian |

| Exoteric | Classical | Classical |

| Esoteric – lower | Classical | Magian |

| Esoteric – upper | Classical | Magian |

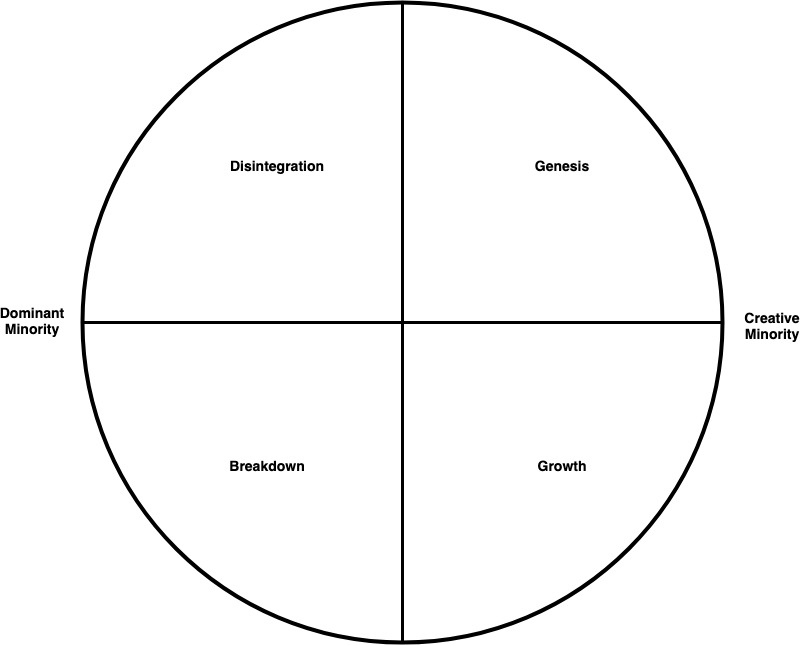

The Magian civilisation is under a pseudomorphosis to the Classical at the Exoteric level of being but retains its Esoteric identity. This is a perfect example of the concept exactly as Spengler defined it. But then something happened that has puzzled scholars all the way up until our time: Christianity became the state religion of Rome. Since Christianity belongs to the Magian civilisation, this implies that the Magian had somehow taken over the Classical even though it was under a pseudomorphosis of the Classical. That’s weird, but it actually fits within both Spengler and Toynbee’s model of history.

Rome represented what Toynbee called the Universal State of the Classical civilisation. The Universal State is the dominant political structure that ushers in a long period of peace and material prosperity. Its arrivals marks the final phase of the cycle of civilisation and the reason is because the Esoteric level of being becomes moribund. We find that life loses its meaning (upper Esoteric) and stagnates in general (lower Esoteric). That’s why the Romans needed circuses to go with their bread. They were bored and needed to be distracted. We can capture this dynamic in our table as follows:-

| Level of Being | Classical | Magian |

| Exoteric | Classical | Classical |

| Esoteric – lower | N/A | Magian |

| Esoteric – upper | N/A | Magian |

The dominance of the Universal State over foreign nations continues and, in general, the Exoteric structures of society remain. They can remain in this petrified state for a very, very long time. Ancient Egypt is the prime example of that. Rome itself lasted many centuries in unchanged form. But life in the Universal State has lost its spark and the civilisation has lost its ability to come up with something new. Therefore, we say that the Esoteric level of being has become moribund, especially the upper Esoteric.

What happened in the case of the Roman Empire, however, was very unusual and perhaps unprecedented. There was, using Spengler’s terminology, a reverse pseudomorphosis, or, we might call it, an Esoteric pseudomorphosis. Spengler describes the situation in almost exactly those terms although, because he had given a specific definition to the concept of pseudomorphosis, he didn’t apply that concept to what had occured. When Christianity became the state church of Rome, we can say that the Classical civilisation was now under an Esoteric pseudomorphosis to the Magian. Note that this is exactly the same analysis that Nietzsche and Gibbon made, although they obviously didn’t use this terminology.

This gives us the following table:-

| Level of Being | Classical | Magian |

| Exoteric | Classical | Classical |

| Esoteric – lower | Magian | Magian |

| Esoteric – upper | Magian | Magian |

The Classical Exoteric forms remain, but now under an Esoteric pseudomorphosis to the Magian.

There are specific developments that made this possible, the most important of which is that St Paul won the argument within the nascent Christian movement to allow gentiles to join the faith. That’s the only reason Romans could become Christians in the first place. A different but symbolically and archetypally important fact is the one I noted a couple of posts ago where the Christian faith explicitly built the Father archetype into its theology, and this seems to match exactly what was going on in the Classical civilisation with a desire for the Father emerging in the cult of Caesar and other developments.

If the dual pseudomorphosis that took place in the late Roman Empire was already unusual, what happened next was even weirder because it was that dual pseudomorphosis that gave birth to Faustian civilisation through the auspices of the Catholic Church that was carried over from late Rome. The symbolism around the Father was now extended to the highest levels of the Exoteric in the person of the Pope, whose title comes from papa, meaning “father” and who is still referred to as the “holy father”. But that symbolism is a direct match with the upper Esoteric in the form of the holy trinity: Father – Son – Holy Spirit. Thus, we have a template that presents a unified structure at the Exoteric and Esoteric levels of being:-

| Level of Being | Faustian |

| Exoteric | Classical-Magian Father |

| Esoteric – lower | Classical-Magian Father |

| Esoteric – upper | Classical-Magian Father |

The Faustian was then born out of a dual pseudomorphosis at both the Exoteric and Esoteric levels of being. This gave rise to a truly uncanny relationship between the Faustian and Classical-Magian which was something that Spengler touched on time and again. In one place, he describes it this way:

“The freedom and power of Classical research are always hindered…by a certain almost religious awe. In all history there is no analogous case of one Culture making a passionate cult of the memory of another.”

But this is the whole point. It was not “almost” a religious awe; it was an actual religious awe that comes from the fact that the Faustian was created by the Classical-Magian synthesis. The parental metaphor here is perfectly apt. The Faustian civilisation was born as a “child” to the “father” of the Classical-Magian dual pseudomorphosis. That would have already been weird enough but what are the odds that the Father-Son relationship would be baked into the very theology itself and which was also represented in the Exoteric forms of the culture through the office of Pope (papa, father)?

We have to remember that theologians used to debate the issue of the trinity furiously, and the trinity is still denied by certain Christian sects, such as the Unitarians. The formulation of these theological concepts into archetypal terms of Father and Son is already a big move psychologically because most conceptions of God talk in abstract terms of a “supreme being” or a deity, or any other term which does not have archetypal resonance in the way that “Father” inevitably does. Can it be a coincidence that this civilisation that was obsessed with the Father would later give rise to the Oedipus Complex?

Freud noted that the son may come to hate the father. Why? Because the father is the dominant power in the household and he prevents the son’s attainment of what he wants (the Esoteric level of being). But that is the exact same relationship that Spengler identified in the hatred of the subordinate culture to the dominant one in pseudomorphosis. It is clear that there is a more general principle which holds both at the individual and collective levels, which makes perfect sense since the collective is made up of individuals. We come to resent and maybe even hate those who stifle our growth and throw our Esoteric and our Exoteric out of balance. That is true of individual people and it is true of entire societies.

But there is another psychology at play, one that Freud also built into the Oedipus Complex. The son may worship and idolise the father. But this is exactly the attitude of the Faustian towards the Classical. Thus, as late as Nietzsche, we find Faustian thinkers who are convinced the Classical civilisation was the greatest thing ever and the thing to do was to try and go back to the glory of Rome.

In truth, both of these Oedipal responses are present throughout the history of the Faustian civilisation. We see equal parts idolisation and rebellion. It’s this exact psychology that Dostoevsky captured so beautifully in many of his novels. We can love and hate somebody at almost the same time. What’s more, the “dominance” they have over us need not be physical in nature. Somebody who is virtuous can be admired for that fact and then hated by the exact same person because their virtue makes that person look bad. The Faustian has always measured itself against the Classical. It idolised it as an ideal to live up to and then rebelled against it when it failed to do so.

Curiously, we see a similar psychology in modern America’s relationship to Europe. Americans will alternately ridicule Europe as an unproductive backwater while also proudly announcing their European heritage. “I’m half Spanish, half Dutch.” “Oh yeah, well I’m half Swedish, half German.” I saw a classic example of this a couple of months ago in a video of a speech by Tucker Carlson, who referred to the Swedish as “my people”. Apparently, he sees no contradiction between such a statement and the fact that he is “America first”. It is these logical paradoxes that are a hallmark of psychology.

And that’s why we must include the psychological point of view when understanding Faustian civilisation. It’s not a coincidence that psychoanalysis would be born of the Faustian. It was the civilisation which needed it – the civilisation of daddy issues which, these days, are turning into mommy issues.