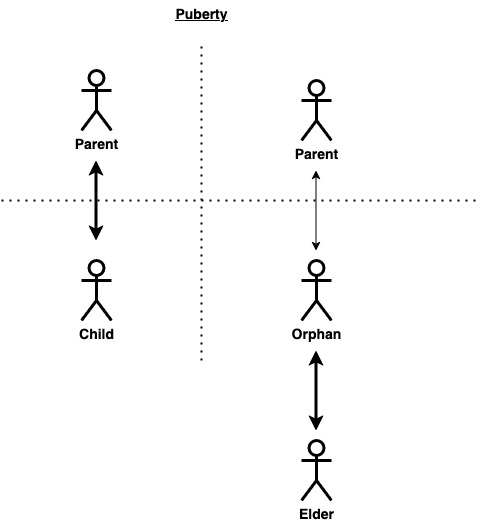

I wasn’t going to write any more in this series, but a commentator (hat tip to Anonymoose) on last week’s post got me thinking more about the question of how stories change over time and what those changes can tell us about broader cultural shifts. Adolescence, as the title makes clear, belongs to the coming-of-age story genre, which is a universal of human culture. When we analyse that story, we find identical tropes that fit with the realities we must face when we go through adolescence. These include stepping out from the dominance of our parents and tackling the challenges of integrating into society.

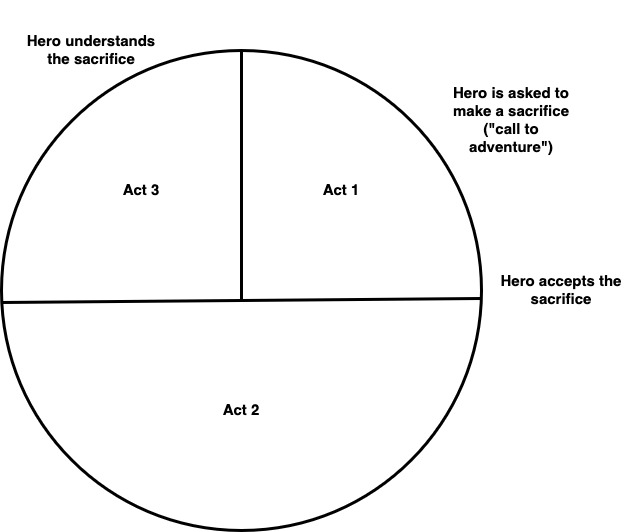

It follows that one of the main themes of any coming-of-age story is the dangers posed by society which can lead the Orphan hero astray. There are always bad elements in any society, and the young, naïve adolescent can easily get in with the wrong crowd. This is often represented by a more general theme in the coming-of-age story, which is the idea that society itself is problematic. We see this idea expressed in one of its purest forms in the movie, The Matrix, where Neo has come of age in a society which is designed to keep him and the rest of humanity from the truth.

The Orphan, who is still little more than a Child, would have no chance of seeing through this illusion or fighting off the dangers of society by themselves. They need help. That help comes from the friends they make in the journey and especially from the Elder who becomes their guide. Thus, Neo has Morpheus to guide him in the right direction and the other members of the Nebuchadnezzar to provide support.

As we have already seen, Adolescence inverts this formula. Jamie has no Elders to guide him to the right path. The closest thing are the teachers at his school, who are shown as being scarcely able to manage their classes, let alone provide any kind of personalised guidance and counselling. This leaves Jamie open to malign influences from the internet. Moreover, Jamie’s friends are also going to lead him astray, as symbolised by the one who provides him with the murder weapon.

The absence of the Elder figure in Adolescence is no surprise. I’ve written at length on the absence of the Elder archetype in modern Western culture in blog posts over recent years and also my two most recent books. The absence of the Elder in story form mirrors its absence in the wider society. This makes sense since, as Northrop Frye correctly pointed out, stories reflect broader changes in the culture. If Elders have disappeared from the culture, one of our main sources to notice that change would be coming-of-age stories such as Adolescence. We might then ask when Elders started to disappear from our coming-of-age stories and why. Now, I haven’t had the time to fully investigate this, but my first guess is that, like so many developments that we take for granted nowadays, it began in the 19th century.

As it happens, we have a prime example of this in the story of Parsifal as it was adopted by Richard Wagner for his final opera. The reason why Parsifal makes such an ideal case study is because the original story was from the medieval period of Europe. The genre of the young knight going off on a great quest was perhaps the most popular coming-of-age story of that era. Therefore, we can compare the coming-of-age story from medieval times against the way in which Wagner adapted it for the 19th century. If we’re correct in saying that changes in stories reflect changes in cultures, then Wagner’s version of Parsifal should be able to tell us something important.

Let’s begin with the original Parsifal. Its author was the medieval knight and poet, Wolfram von Eschenbach, and it was written in the 13th century. The story begins with Parsifal’s father, Gahmuret, whose own father has just died. Gahmuret’s father was the king, and, in line with the inheritance rules of medieval Europe, he leaves his entire kingdom to his eldest son, Galoes. Galoes has magnanimously offered to give Gahmuret a segment of the kingdom to rule over, but the young man rejects the offer and leaves on the classic knight’s quest to find fortune and fame.

Here we see the close correspondences between fiction and reality that Northrop Frye was interested in. In the real world of medieval Europe, it really was the younger sons of the nobility who became knights. Because the eldest son received the entire inheritance, the younger brothers had very few prospects in life. Quite a lot of them turned to gambling, whoring, and crime. A less illegal option was to become a knight, not least because this increased the marriage chances of the young man. That’s why the classic knight story usually has the hero winning the heart of a virtuous maiden. In general, we might characterise the medieval knight story as a coming-of-age story for the men of the lesser nobility.

In von Eschenbach’s story, Gahmuret rejects the offer to settle down and travels first to Africa, where he beats the bad guys, marries a beautiful queen, and becomes king. But he gets bored with that and returns to Europe to marry Queen Herzeloyde. It doesn’t take long for his second marriage to also bore him, so he ups and leaves, travelling this time to Baghdad to fight on behalf of the ruler there. On this occasion, however, his luck runs out, and he is killed in battle.

The good queen Herzeloyde, meanwhile, is pregnant with Gahmuret’s child. Upon hearing of her husband’s death, she retires to the forest to raise her young son, Parsifal, away from the stories and temptations of chivalry that brought her husband undone. That tactic works well until Parsifal becomes a teenager (archetypal Orphan). Some knights come through his neck of the forest and tell him about the court of King Arthur. Entranced by the idea of knightly adventure, Parsifal runs off to join the king’s court. His mother is so heartbroken that her son is following in the footsteps of his father that she dies.

Note that this beginning to the story follows the template we identified in last week’s post. Parsifal is entering the Orphan phase of life and the death of his mother means that he is now a literal orphan too. The queen has attempted to shield her son from what she perceives as the bad influence of society. Her anguish at having to let go of Parsifal is the same as that felt by Eddie in Adolescence. In this respect, we can see a parallel in two stories that are separated by almost a millennia. It is the anguish of the Parent who must give their Child over to society, knowing all the dangers that lurk therein.

However, in the original story of Parsifal, the young man is not going to come to ruin, and one of the main reasons for that is that he immediately meets with the Elder who is going to induct him into the ways of knighthood. Almost the first thing that happens after Parsifal leaves his mother is that he comes under the tutelage of Gurnemanz, who will train him as a knight. In addition, he will make new friends who will help him on his journey, the most important of whom is Gawan. There follow a whole lot of other side quests in the usual medieval knight-story fashion, but the overall arc of the story is Parsifal’s coming-of-age as “Grail King”. The story finishes with Parsifal and his wife living happily ever after.

With this very brief outline, we can see that the original Parsifal matches Adolescence in showing us the grief felt by the Parent who must let go of their Child. One of the main differences in the stories lies in the absence of the Elder archetype in Adolescence and also the fact that Jamie’s friends are not a good influence on him but a malign one. As a result, Jamie is led astray by society, while Parsifal successfully navigates the Orphan phase of life and graduates to adulthood at the end of the story.

Now, if we fast forward to Wagner’s rewrite of Parsifal, which premiered in 1882, we can see that composer made some major changes to the story. Crucially, however, Wagner’s Parsifal is still a coming-of-age story. Therefore, we can compare it to the medieval one and hypothesise that the changes that Wagner made mirrored changes in the wider culture.

It’s worthwhile remembering here that Wagner was incredibly popular in his day, and so the cultural influence of his stories is comparable to those of the medieval myths he adapted. There was even a Wagner society here in Australia that performed some of Wagner’s works during his lifetime, and Wagner considered moving to the USA later in life since he was very popular there too.

Anyway, Wagner’s version of the story begins with Gurnemanz at the seat of the grail. We know that Gurnemanz is still playing his role as the Elder because we see him giving instruction to a group of squires. Thus, when Parsifal stumbles into the scene, we expect Gurnemanz to take him under his wing and turn him into a grail knight. That begins to happen, but then Wagner quite explicitly overthrows the standard plot arc of the coming-of-age story.

In the original version of the story, Parsifal’s mother did not want him to become a knight. To try and trick the older knights into rejecting her son and not giving him initiation, she had dressed him like a fool. That doesn’t work in the story because Parsifal wins a duel, thereby showing the knights what he is capable of. As a result, Gurnemanz becomes his Elder.

Wagner takes the fool trope from the original story and makes it central to his version. Parsifal is not just dressed like a fool. He is a fool. Nietzsche would later refer to him as a “country bumpkin”, and that is quite accurate. In Wagner’s story, the fact that Parsifal is a fool is what interests Gurnemanz because the knights of the grail are in dire straits, and it is prophesied that a “pure fool” will redeem them. Gurnemanz originally thinks Parsifal could be that fool. But when he puts Parsifal to the test, he is proven wrong. Parsifal is not a pure fool; he’s just a garden-variety village idiot and Gurnemanz angrily sends him away.

Within the first act of Parsifal, Wagner upends almost all the main tropes of the coming-of-age story. The Elder is supposed to recognise the potential of the young Orphan. That is what Gurnemanz does in the original Parsifal. It is what Morpheus does with Neo in The Matrix. It is what Obi-Wan does with Luke Skywalker in Star Wars. Wagner’s Gurnemanz, however, does not recognise Parsifal as being the pure fool and sends him away. Therefore, Parsifal receives no initiation at all.

At this point, we might expect Parsifal to get into big trouble in the same way that Jamie does in Adolescence. Without a wise Elder to guide the way, the foolish Orphan can easily be led astray. Wagner raises that exact possibility by having Parsifal wander straight into the lair of the bad guy, Klingsor. Imagine Luke Skywalker having to confront Darth Vader at the start of Star Wars or Neo having to confront Agent Smith at the start of The Matrix. Would we expect the untrained young man to defeat his more experienced opponent, or would we expect him to get gobbled up by the bad guy? Obviously, the latter is going to happen.

Yet, Wagner also inverts this trope too. Parsifal will see through the illusions of Klingsor and defeat him. Klingsor represents the dangerous element in society that can destroy the young Orphan. Much like the Matrix is an illusion set up to deceive Neo, Klingsor is the master of deception. In that respect, he’s directly analogous to Agent Smith. Yet, somehow, Parsifal, the village idiot, is able to see through it all.

There are more elements to the story, but those are the main themes that we need to understand how Wagner inverted the coming-of-age story with his version of Parsifal. In Wagner’s world, the Elder is no longer required because the Orphan’s foolishness is exactly what he needs to see through the illusions of society. In fact, Wagner is stating that the Elders of the grail are themselves trapped in illusion and need to be redeemed by the young man (this is actually what happens at the end of the opera).

We might be tempted to put all this down to the strange genius of Wagner. Many commentators have thrown up their hands and suggested that Wagner’s rewrite of Parsifal is not even a real story but must be understood allegorically. That is definitely not the case. Wagner quite systematically inverts the coming-of-age story.

If this was an isolated event, we might not say that it had any relevance to wider cultural trends. However, incredibly, at almost the exact same time that Wagner was working on the libretto for Parsifal, another great writer was constructing a work that presents us with an almost identical inversion of the coming-of-age story.

Wagner had been toying with the Parsifal story for decades but only set out to write the final version in 1876. At exactly the same time, the ideas for what would eventually become The Brothers Karamazov were taking shape in Dostoevsky’s mind. He began working on the novel itself late in 1877. Another really strange coincidence here is that Dostoevsky would die just months after Karamazov was released, while Wagner also passed away just six months after the premiere of Parsifal. Both stories would be the last and perhaps greatest works of two artistic giants of the 19th century.

There is one more strange and tragic parallel. Dostoevsky’s young son died in early 1878. His name was Alyosha, and that became the name of the hero in Karamazov. At almost the exact same time, Nietzsche sent Wagner a copy of his latest work, Human, All Too Human. That work made official the break between the two men. The break was incredibly painful for Wagner, who genuinely thought of Nietzsche as a member of his family (Wagner had actually considered making Nietzsche his son’s legal guardian in the event of Wagner’s death). It seems almost certain that Wagner had intuited this break in 1876 when he was writing Parsifal.

(In fact, I believe Wagner wrote Parsifal with Nietzsche in mind, but that’s an argument that will need an entire book to make, a book that I am currently in the process of writing, working title The Initiation of Nietzsche).

What this means is that both Dostoevsky and Wagner were in the process of grieving over the loss of a son in one case and an adopted son in the other, just as the archetypal Parent must grieve when their Child becomes an Orphan. It’s impossible to believe that these events didn’t have an influence on Parsifal and Karamazov.

More broadly, both Wagner and Dostoevsky were horrified by the rise of modern rationalism, which they each correctly saw as little more than a cloak for psychopathic politics. Nietzsche’s eventual solution was to embrace that development. If you’re going to be a psychopath, you might as well do it properly. Wagner’s solution was Parsifal, the pure fool. But Dostoevsky had hit on almost the exact same idea at the exact same time.

In Karamazov, the pure fool is the lead character, Alyosha. Just like Parsifal is sent away from the corrupt knights of the grail by Gurnemanz, so too Alyosha is sent away from the corrupt priests of the church by his Elder, Zosima. In both cases, the Orphan character explicitly does not receive initiation. The broader point is that their purity and innocence of character are what will allow them to confront the evils of the world. Any training that an Elder can give is only ever going to be a distraction from that.

Now, it’s not entirely true to say that Zosima and Gurnemanz provide no guidance at all. What they both do for their young charges is to show them suffering in the world. Gurnemanz does that by inviting Parsifal to witness a ceremony involving the perpetually wounded Amfortas and his dying father. Zosima does it by having Alyosha accompany him on his missions to assist the common folk who are facing distress. What Parsifal and Alyosha must do is face that suffering without losing the qualities of the pure fool. In fact, their foolishness leaves them open to understanding that suffering directly because they do not know how to construct the psychic and emotional barriers that normally protect us from the suffering of others.

One of the main themes that runs through the work of both Wagner and Dostoevsky is that the rationalism of modern society is a form of corruption. Initiation into that overly rational, left-brained world can therefore only corrupt the Orphan too. The solution is a direct confrontation with reality in all its potential ugliness.

Quite by accident, the writers of Adolescence show something very similar, since Jamie’s “initiation” is at the hands of the modern justice system, which is very rational and well-organised with its professionals who are all efficient at their jobs. Jamie’s cry at the end of episode 3, “Do you actually care about me?” is all the more chilling for the fact that Adolescence portrays the rational ones as the good guys in the story. What is completely lacking on the part of those professionals is empathy for the young man.

Of course, it is no easy task to empathise with a murderer. Dostoevsky explored that theme in detail in Crime and Punishment, where the only person who knows how to empathise with Raskolnikov is Sonya, who is very similar to the character of Kundry in Wagner’s Parsifal; a redeemed sinner.

By contrast, in Adolescence, there is nobody around to care about Jamie because there is nobody who knows how to empathise with him. As Wagner and Dostoevsky knew, we live in a society where this kind of empathy is almost completely lacking. That’s what an over-reliance on rationality gets you. As G. K. Chesterton so beautifully put it, “Objectivity is just a fancy word for indifference.” Jamie is cast into a world where nobody cares. They’re just doing their job.

Apparently, with the success of the show, the writers of Adolescence are thinking of making a second series. I don’t expect for a second that it will happen, but there is a potential plot arc to the story that would allow it to explore the themes that Wagner and Dostoevsky covered more than a century ago. It would be a redemption arc for Jamie involving him coming to terms with the murder he has committed.

For that redemption to occur, Jamie would need would be the empathy of a fellow sinner. Following in the footsteps of Wagner’s Kundry and Dostoevsky’s Sonya, it could be a young woman who has come to terms with her own sin. Since both Sonya and Kundry are redeemed enchantresses, the obvious character in the modern world would be a beautiful young OnlyFans model who has seen the error of her ways. Perhaps she would see Jamie’s story in the news and start visiting him in jail.

A redemption arc for an online porn star and an Andrew Tate follower. That would be a coming-of-age story worthy of a Wagner or a Dostoevsky.