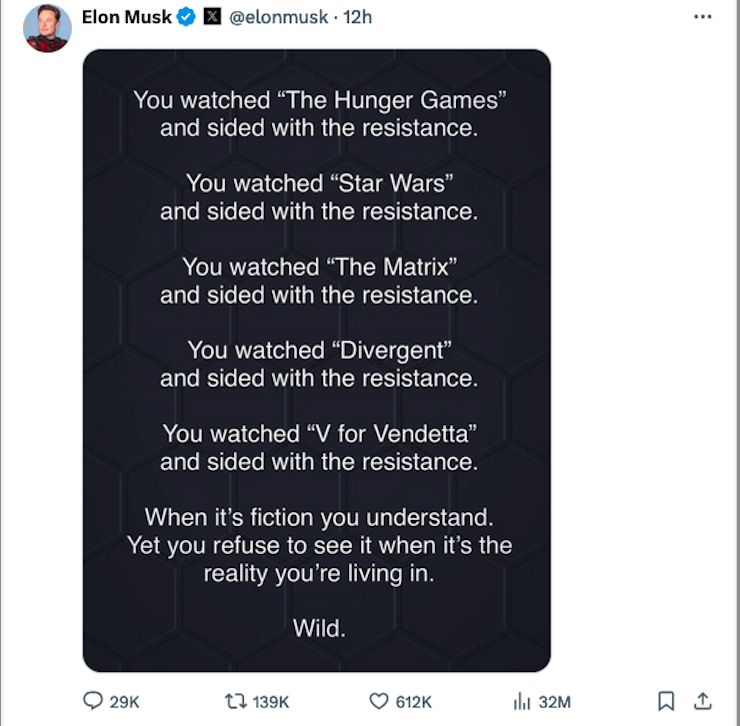

During the week, I happened to stumble across this post by Elon Musk:

Since a very great deal of my writing over the past few years has been about stories (of the literature and film variety), it’s fair to say that Musk’s post struck a chord. But there’s much more to it than that.

Two of the films that Musk mentioned, The Matrix and Star Wars, were at the core of my analysis in my most recent book, The Universal State of America. In turn, those two films belong to the larger pattern I have called the Orphan Story, which is the archetypal narrative about the Orphan phase of life, the time when we must leave childhood behind and establish our adult identity.

In fact, all five of the movies that Musk mentioned are archetypal Orphan Stories featuring a hero who must come of age. But they are also a very special type of Orphan Story because they all take place against a backdrop of authoritarian politics. What sets these Orphan Stories apart is that the hero is coming of age in a dystopian society. In each case, the Orphan hero joins the “resistance” and rejects the dystopia offered to them.

It is usually the Tyrannical Father archetype who is at the head of a dystopia. Star Wars has perhaps the most famous example of this dynamic in recent memory since Darth Vader is both the socio-political Tyrannical Father and also the personal Tyrannical Father to the Orphan hero of the story, Luke Skywalker. As I explained in The Universal State of America, The Matrix provides us with the unusual pattern of a dystopia led by the Devouring Mother archetype (a tyranny without a tyrant).

Now, I don’t suppose that Elon Musk has read any of my books or any of the posts on this blog, so what are the chances that he would select five stories that are Orphan Stories? After all, he could have cited any number of dystopian books or films that are not Orphan Stories. 1984 is a popular one these days. There’s Brave New World, or Blade Runner, or The Machine Stops, or any number of others. Instead, Musk chose all Orphan Stories.

What’s even weirder about that is that Musk has recently aligned himself with the Trump presidential campaign. His post was clearly meant to associate Trump with the “resistance”. Since he used Orphan Stories to make that point, he was also associating Trump supporters with archetypal Orphans.

That exactly matches the analysis I originally made in my book The Devouring Mother, where I noted that the Trump and Brexit votes were indicative of what I called the rebellious Orphans. Those elections were clearly a rejection of the current status quo in the modern West, which was ushered in by the neoliberal agenda back in the 1990s. As such, they were a rebellion against a system that has, in fact, become far more authoritarian in recent years.

Although I still broadly agree with this framing of what is going on, it also has to be said that the Orphan Story-Dystopia paradigm is used by both sides of politics in the United States.

The Democrats have their own version of the Orphan Story-Dystopia framing. In that version, Trump is Hitler, and those who support him are “far right” neo-fascists. In archetypal terms, Trump is placed into the role of Tyrannical Father who’s going to take away your “freedom”. The “resistance” then becomes the people who oppose Trump, since they are opposing tyranny.

In short, both sides of politics are using the exact same story about struggling against an authoritarian political system. This gives us the weird spectacle of people voting in a democratic (non-authoritarian) system who are fully convinced that authoritarianism will take over if the other team wins.

From a propaganda point of view, it’s not surprising to find both sides of politics using the same underlying story, since narrative structures provide ready-made slots into which you can insert the good guys and bad guys of your choice. But what I realised after thinking about it a little more is that there is one sense in which the Orphan Story – Dystopia pattern is actually symbolically representative of democracy in general and the US presidential election more specifically. To understand why this works, we need to go over the underlying pattern that is at play.

That pattern is the cycle. It was Joseph Campbell who found that the structure that underlies every story, including seemingly all cross-cultural myths that we know of, is a cycle. He called it the Hero’s Journey.

Not surprisingly, every Hero’s Journey features a hero. What is less obvious but equally true is that every Hero’s Journey also takes place against a socio-political backdrop. This is true even in mythology, where the interactions of the gods imply a socio-political structure that is recognisable in the culture to which the story belongs.

We can, therefore, group all Hero’s Journeys according to the larger cycle of the human lifespan but also according to the cycle of the societal background against which the story takes place. This latter point was a core insight of Northrop Frye, who followed the work of Giamattista Vico in realising that certain types of narrative genre predominate at different parts of the cycle of civilisation.

We can carry out the exact same analysis with the “seasons” of the human lifecycle. Thus, childhood and adolescence (the Child and Orphan archetypes) map to spring, early adulthood to summer, late adulthood to autumn, and old age to winter.

With this framework in mind, we can see that the Orphan Story-Dystopia pattern involves a hero in the springtime of their own life living through a socio-political epoch that represents the winter phase of the civilisational cycle. Dystopia has its mythological grounding in the winter phase of Frye’s cycle.

In mythology, however, winter was just the prelude to spring. Just like the seasons of the year, the cycle does not stop but keeps turning. Thus, the “winter” phase usually denoted a death-rebirth motif. The god or goddess dies in winter and is reborn in spring, signalling the beginning of a new cycle.

We can see, therefore, that Hero’s Journeys are mini-cycles which take place against the implied larger cycles of the human lifespan and the rise and fall of civilisations.

Ok, but what does all this have to do with democracy? Well, democracy is also a cycle. In the USA, the presidential cycle runs for four years. At the end of that cycle, a president “dies” and is “reborn” after an election, just like the mythological gods of old. It follows that the period leading up to an election is the winter phase of the cycle. The old president is dying and needs to be replaced by new life (with the advanced age of modern presidents, this is quite literally true!).

Thus, the Orphan Story-Dystopia pattern is actually a perfect symbolic representation of the end of a presidency. The Dystopia refers to the dying world of the incumbent presidency. It is the socio-political backdrop to the Hero’s Journey. The Hero’s Journey is an Orphan Story featuring the candidates who are vying to become the newly risen president who will usher in a new era. One of those candidates will “come of age” as the new president.

In this way, the apocalyptic tone that seems to arise in the lead up to every American presidential election is at least partly driven by the imposition of this ancient mythological frame onto proceedings. For every election, a great many people are convinced that if their hero (presidential candidate) doesn’t win, the entire world will come to an end. That belief is irrational, but it resonates because of the mythological framework that is invoked.

Note that this mytho-apocalyptic lens only seems to appear for presidential elections and not for midterm election. The obvious reason for this is because presidential elections have a hero figure and this triggers the Hero’s Journey archetype. Every Hero’s Journey needs a hero. The president gets cast as the mythological hero of old.

It’s worth remembering that the US is rather unique among modern western democracies in allowing the public to vote for the head of state and therefore to elect a new hero every four years. In other nations, even nominal figureheads do not fulfill the hero archetype.

Here in Australia, for example, it’s common for Prime Ministers to get knifed by internal factional maneuverings. They are usually replaced by lunchtime the next day. It’s an efficient, rational system, but certainly not heroic, and therefore not worthy of the grand mythologies that surround the US presidential race.

Hi Simon,

A very cheeky observation, but yes, it is literally true the winter senescence for that particular person is very advanced. Don’t you think it is interesting that the person was left in the role, when even before the debate it was clear that there was a lot going wrong there? To my mind it raises the obvious question, who then is at the helm and what do they gain from the situation.

That was an eerie post from Mr Musk. He may benefit by receiving a copy of your book.

In many ways, the US is really going through a death re-birth cycle right now. It’s a difficult time to lose one’s Empire.

Incidentally, this analysis is a very good starting point for your ‘Universal State’ book.

Cheers

Chris

Chris – that’s the irony of the situation. Presidential elections have this heroic mythology surrounding them when the fact is that the majority of the US government is run by the bureaucracy/congress. The entire role of president is a kind of strange mythological anachronism and arguably has been ever since George Washington’s time.

Hi Simon,

It is ironic isn’t it.

Hey, one of my readers brought this to my attention. Have you ever noticed that the US and the UK have the archetypes: Columbia and Britannia?

Cheers

Chris

Chris – hmmm, never thought about that. Still, it’s quite common to represent nations in human form. Although it would be considered a bit antiquated these days, people also used to refer to their home country as the “motherland” (or “fatherland”).

Simon,

I read a book by David Greaber called “On Kings” that sheds an interesting light on the anthropology of kingship in general. This is one of his more academic work, and to my understanding represents some of his research in anthropology, his field.

Since anthropologists are often interested in the stories societies tell about their customs, I find this part of anthropology an interesting intersection between social studies and mythology.

In his book, Greaber talks about the character of the king. According to Greaber, the king is often looked upon as sacred, while his people are “profane”. By being sacred while everyone else is profane, the king is removed from all personal societal relationships, so if two of his people were to have a dispute, and would come in front of him, he would be able to be completely impartial. The story of the trail Israelite king Salomon from the hebrew bible conducted between two women who argued over custody of a baby comes in mind.

In order to transform a person into a king, who is a sacred figure, societies often develop elaborate ceremonies. Greaber gives detailed examples, one that I seem to remember well comes from a society in Africa where if memory serves me, the would be king performs a pilgrimage of sort to the capital city accompanied by his supporters, where a mock battle would be staged. This sounds a lot like a hero’s journey, and this could be what the US presidential elections are meant to mimick.

In Greaber’s theory of kings there is however a second phase that comes after the hero’s journey ends, where the would be king is removed from the profane to the sacred. This is sometimes done by a breaking of a taboo. Greaber brings an example of a society where on coronation night, the king is “caught” in bed with his sister, implying he committed incest. In this society, this is staged – they were normally laying in bed next to each other with their clothes on, but in other societies like Ptolemaic Egypt they took it a step farther and actually married their sisters. Other times, the king would perform random acts of murder, to demonstrate his is above the law and societal norms. Greaber brings an account of an king in Africa who was given a rifle by a European power, and proceeded to test it on a random passerby.

I guess a modern western would understand this not as making the king sacred, but rather as a hero who became a villain. It is very common for Americans to become disillusioned of a president they elected, and this stage in the king’s “lifecycle” coupled with modern western understanding of the hero’s journey may serve to explain this. What’s interesting is that unlike other past societies who understood this as a necessary and even beneficial step for a society, in the US this is often thought of a something that should end a presidency, but in practice rarely does (Bill Clinton’s affair comes to mind – he eventually finished his remaining term).

Another thing that seems to happen to kings after their hero’s journey is that they become children. Societies often treat the king like a child: His every need is being meet, he is often confined to a palace that serves to both isolate and protect him from the outside world, and he is often surrounded by a group of trusted supporters (sometimes the supporters who accompanied him in his hero’s journey), who often take the actual responsibility of running the state in practice. In the US this is done by the bureaucracy – the president’s “administration”. In the US even those trusted supporters are usually just figureheads – the president often just appoints his secretaries, who each head a huge bureaucracy, but you still see this pattern.

So, we see the king is often turned into a sacred child of sorts. He often has a group of people, in modern states often bureaucrats, but sometimes military officers, priests or other elite professions, who act as his mother – who keeps him as an eternal baby – taking care of his needs, but also preventing him from ever having actual responsibility.

Greaber talks about societies where the mother is a devouring mother – in some societies, the king ends his reign by his supporters ceremonially killing him. In some societies this is so formalized a king knows this is how things will end. In the US system, we may have seen a similar thing – Biden was probably forced to withdraw from elections by the very democratic party bureaucracy bureaucrats that helped him get elected, and replaced him with his vice president. It remains to be seem how well does she fight the mock battle of elections.

This model is interesting, because by turning the king into a child, the process of the hero’s journey is essentially reversed. I understand the US presidency as a drop in replacement of the king of England. After overthrowing their English mother, the founding fathers still felt the need for a king figure, but they wanted him to not be above the law (by placing constitutional and judicial checks and balances), and probably never intended for the second phase to start – the constitution has no mention of secretaries or parties, and the president was originally expected to quit after two terms of his own will (showing maturity and discipline – unlike a child). Even the existence of the white house, a modern palace, was never mentioned in the US constitution.

This changed over the years, and now we may be seeing how Americans deal with their new sacred child presidents. It would also explain why Trump does so well, as a reality star he has no problem with scandals that would help him become sacred. In a way, the US may have become a constitutional monarchy of sorts.

Bakbook – I still haven’t read Graeber, though he’s been on my to-read list forever, but that all sounds correct from my reading of the anthropological literature. The only thing I would disagree about is the idea that the president is a child. That might be close to the actual truth and I think the bureaucracy as Devouring Mother would want the president as child for strictly political reasons. But a large section of the public wants the president to be a hero.

Incidentally, the idea of two-year terms began with the original hero-president, George Washington. He refused to serve more than two terms and it became the tradition that every president would follow him. That lasted all the way until Roosevelt who did four terms due to the war. Following him, a law was passed that the president may only serve two terms.

One other slight quibble, the American colonists were overthrowing the English Tyrannical Father (George III) not a Mother-figure. You’re right, though, that the presidency was born out of a desire to still have a patriarchal figurehead.

The pattern of getting rid of a father-figure only to replace him with another seems quite common. It happened also in France where the Tyrannical Father, Louis, was gotten rid of only to give rise to the heroic figure of Napoleon. Arguably, the same dynamic happened with Hitler, Stalin, Mussolini etc. Contrary to the Enlightenment dream, there does seem to be a deep-seated human needed for an authority figure.

Hi Simon,

“there does seem to be a deep-seated human needed for an authority figure.”

There is an element in that story of society rejecting the current status quo, then probably quietly (or loudly, choose your poison) hoping that a new leader ushers in a less dysfunctional set of arrangements. History suggests this rarely ends well in the short term, but over the slightly longer term maybe things got a little bit better. Look at how the Puritans in England were rejected – like what could be wrong with pies and gingerbread men? – and Charles II was then invited back, albeit with some modifications.

Dunno, but there is an element to the story which suggests that the ‘modifications’ became inevitable once the conditions on the ground become untenable. There’s an old saying about ‘what is unsustainable is rarely sustained’. It’s the rare leader who’ll get to that position by promising less for themselves and their peers. Look how hated President Carter was and is perceived, but I reckon the dude was onto something there.

What’s your views on that?

Cheers

Chris

Chris – I don’t know much about Carter. I think I’ve only seen the fireside chat video. What I thought was interesting in that was that he talked about the need for meaning rather than consumerism. I suspect he was ahead of his time on that issue too. Still, it’s not really something that presidents can solve and all the evidence suggests that “it’s the economy stupid” when it comes to winning elections.