I have been dabbling with gardening for about ten years or so, but it wasn’t until corona that I got more serious about the food-producing side, and that was mostly because I didn’t have much else to do during the two wonderful years of lockdowns that we got to enjoy here in Melbourne.

Coincidentally, 2020 was about the year that the fruit trees that I planted earlier in my yard were starting to come to maturity and generate decent yields. I then started to expand my vegetable beds. By 2022, I was getting decent enough yields that I decided to start measuring them to see what they were worth.

Now, I wouldn’t say I am active in any gardening forums, but I am a member of a gardening society here in Australia (Diggers club) and I’ve been to a number of permaculture workshops and know people in that space. In addition, I am always looking up gardening-related stuff online. What I realised recently was that I have never seen a single article, blog post, or YouTube video that addresses the question of the monetary value of homegrown food. Because of that, when I calculated my results, I got quite a surprise, which I thought might be worth sharing.

The results I’m about to present were measured in the 2022-23 year. It’s worth mentioning that, although my skills and knowledge had improved by then, I was and still am an intermediate gardener. If what I read online is correct, skilled gardeners are getting about twice the yield I got in 2022-23, especially for things like tomatoes. So, the numbers I am giving are on the low side, especially for the vegetables.

Another thing to bear in mind is that I only measured what made it to the kitchen, and that was less than what actually grew. So, again, the numbers are lower than what they could have been.

These caveats do not affect the overall result; in fact, when corrected for, they make the result even more stark. Let’s look at the numbers. I’ve rounded to the nearest dollar for clarity.

Vegetables:-

| Crop | Yield in $ per m2 |

| Cucumber | $45 |

| Chilli – jalapeno | $32 |

| Tomato – black Russian | $30 |

| Tomato – cherry | $25 |

| Potato | $10 |

| Corn | $7 |

| Carrot | $5 |

| Garlic | $3 |

Fruit and nuts:-

| Crop | Yield $ per m2 |

| Lemon | $10 |

| Pear | $6 |

| Apple | $4 |

| Olive | $3 |

| Almond | $3 |

There are two other results that I had last summer that are worth mentioning here. Both berries and capsicums come in at about $35 per square metre, placing them in the top tier.

These numbers paint a very clear picture: the most valuable things to grow in the garden are summer vegetables, with the humble cucumber sitting as king on the throne! However, I suspect that tomato is probably the real king. This year I expect to get at least a 50% greater yield than I got in the summer of 2023, which would put tomatoes on top.

The real eye-opener from my point of view was the fruit. My olive trees still have some improving to do, but the apples, pears, and lemons are all producing at what should be close to their maximum yield. Despite that, we can see that the value per square metre is low. Trees, of course, take up a lot of space, so this makes sense.

The general rule here seems to be that vegetables are about an order of magnitude more valuable to grow than fruit. This is especially true in my climate, where I have a year-round growing season, and so any square metre of vegetable bed produces both a summer and a winter crop (and potentially even a third crop if I really pushed it).

The lesson from this is very clear: if you are looking to maximise your return on investment, you should grow vegetables first and only bother with fruit if you have space, time, and energy left over. Vegetables have other advantages too. As I mentioned, in my climate, I can grow vegetables all year round, and I can stagger the planting to get essentially a continuous supply as opposed to most types of fruit, which have to be harvested in one big bang.

This raises a fascinating question: why did I have to learn this myself? Why is this message not prevalent, at least in the gardening communities that I have interacted with? I have some ideas why this is the case, but I think the interesting thing is that this lesson was actually present in the original organic gardening movement. That movement distinguished between intensive and extensive crops.

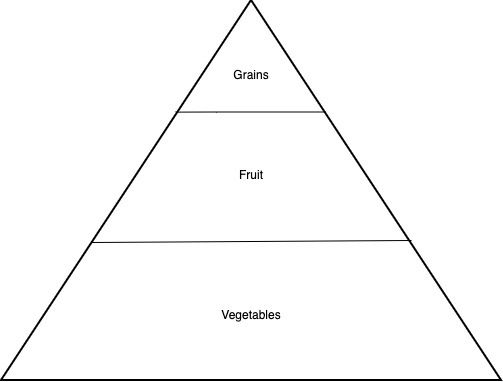

It turns out that my calculations on the value of food exactly map to that intensive-extensive distinction. Vegetables are intensive, and they are distinguished from grain crops, which are extensive. Fruit trees are somewhere in the middle. This gives us a classic pyramid pattern:

For a fixed area of soil, the value of the yield is greatest for vegetables and least for grains, with fruit somewhere in the middle. Thought about another way, to get the same aggregate value from fruit trees requires far more land than for vegetables, while grains require even greater amounts of land. Given that the amount of area under cultivation corresponds to the amount of work required to manage it, less area equals less effort equals more value. Whichever way you cut it, vegetables come out on top.

Intensive vegetable growing allows you to concentrate your efforts. You concentrate your watering, your digging (if you do any), and, most importantly, the organic matter you have available. That’s why composting and mulching are a natural fit for vegetable gardening but become less viable for fruit and grain farming at scale.

There is some interesting work being done these days on using teas to scale the benefits of compost to extensive crops. It would be nice if that turned out to be true. But even if it is true, you’re still doing extensive agriculture, and that means less dollar value per time and money invested.

Now, I mentioned that I had my theories about why the economic angle is excluded from consideration in gardening circles. Let me just give the most grandiose of those.

Most people would know that the Reformation created our modern separation of church and state. Another way to frame that is that it separated economic concerns from spiritual ones. That is actually unusual. If we look back in history, we find that economics, politics, and religion were all mingled together. In fact, temples and churches were often a place of economic exchange.

We have gotten so used to this state of affairs that we tend to think that any pursuit that is not overtly “economic” must exclude economics altogether. Could that be why modern gardening movements like permaculture never talk about money but frame their approach as getting in touch with nature or something similarly spiritual sounding?

The trouble with that, I think, is that I suspect we humans have an inbuilt economic compass. This is also a feeling, very similar to the feeling of being in tune with nature. I think we “feel good” when we do things that have economic value, and we feel bad when we don’t. This was the implication of David Graeber’s concept of bullshit jobs. People who have jobs that they know produce no value suffer anxiety. The opposite is also true; there is an inherent satisfaction to doing something of value.

In fact, I’d say that’s the number one reason to grow food. We live in a society where it is really, really hard to create value since everybody already has too much of everything. Doing something simple and straightforward that creates real value connects back to our economic instincts.

As a 68 year old psychiatrist, Jungian and now a prepper I totally agree. I grew my vegetables at latitude 57 and have also one cow, one sow and hens. I produce food for me and my wife, children and grandchildren. The routines and manual work helps me to reduce anxiety. It is also easier to understand the basic circumstances for life in balance with nature, but also when modern way if life is counterproductive.

Olle – I’m guessing you don’t get a winter crop at that latitude 😛

What’s interesting about that is that the financial value per square metre doesn’t correspond to the nutritional value per square metre. Those summer veggies at the top are technically botanical fruits too, hence their high yield on your chart because they keep going through the season. Good luck living off them though.

I’ve seen this myself on the farm, the market often rewards you for growing things that are head scratching from purely soviet style food management perspective. Who said markets were rational?

Simon: “We live in a society where it is really, really hard to create value since everybody already has too much of everything.”

Too much of everything except land, Simon, except land. 😉 Which has gotten absurdly expensive in many places, as you’ve written yourself. Maybe the reason that no-one mentions the monetary angle of vegetable growing is that a m^2 of land costs so much that it would take decades of cucumber yields to pay off that m^2? So, it makes no sense monetarily. Though you could certainly make the argument that you have that m^2 anyway and aren’t about to sell it, and so you might as well grow vegetables rather than, I don’t know, grass.

Skip – when cucumbers are the most valuable thing you can grow, something is definitely wrong 🙂

That’s a good point about the nutritional perspective. Ranking by nutritional value, I think chicken’s eggs would come out on top followed by potatoes. Correcting for nutritional value, potatoes are probably the most valuable thing you can grow. Everything else then becomes a flavour additive with a vitamin boost.

Irena – yes, that’s the very obvious reason nobody talks about the money side. I could take the 50m2 I grow vegetables/berries on, build a one bedroom dwelling on it and rent it out for several orders of magnitude more money that I will ever get from growing food. Which is of course Australia’s main business model these days.

Yeah I remember reading it’s potatoes and it’s not particularly close. I’m guessing some combination of vertically grown potatoes (boxes stacked up and up) and then a big enough fish pond or chicken coup with a few leafy greens would almost provide enough to live off in an emergency. The three sisters would be pretty high too.

Something worth trying is growing wheat in your backyard, and devoting the same of amount of fertility and water to it that you would to other vegetables. Wheats protein content and yield is enormous under perfect conditions, and when you eat the bread grown in this manner you can understand how a ploughman’s lunch could keep someone going all day doing hard physical labour. The grain stores basically indefinitely too.

It makes you appreciate why the Gods our ancestors worshiped were grain Gods.

It might be apocryphal, but I once read that Napoleon’s nightly meal when marching on Russia was fried potatoes and onion. Potatoes are also dead easy to grow and don’t need to be protected from birds and bugs.

Interesting point about the wheat. I might experiment with that. Fun story about bread. For centuries, European peasants lived on whole grain bread. The French aristocracy had started to eat white bread, which had essentially no nutritional value in those days. After the French Revolution, all the peasants decided they wanted to eat white bread and everybody started to get sick cos their diet had no nutrients in it all of a sudden.

Hi Simon,

🙂 Oh my, another sacred cow, skewered. For your information, I don’t track the economic side of the equation, because it simply makes no economic sense. Forget about the land cost, The fertilisers and soil additions for the potato crops cost about $150, whilst the economic value of the produce will be about $300 – locally they’re about $2/kg. That assumes no fencing, no water infrastructure charges, free ongoing maintenance. It’s bonkers.

However, the quality of the soils right across the planet are declining, so the hard question is: what exactly are you eating? Economics misses the protein and mineral qualities of the produce.

Also, being paid on weight of the produce can lead to unusual outcomes such as lower proteins and higher carbohydrates in foods.

Basically my best guess is that like many things, food is mis-priced.

Cheers

Chris

Chris – I saw an article the other day which is what got me thinking about this topic again. It was an MSM piece that said something like “organic food no better than industrial agriculture”. The article made the claim that organic has no nutritional advantage over food grown with mineral additives. Ironically, that still makes organic superior since the whole point is what is not in it: pesticides, herbicides etc.

So far, I’m getting very good results using only compost for fertiliser. The secret is the chicken manure from the coop. My back of the envelope calculations suggest that I’m adding about 3kg of manure per square metre of garden bed per year. Alongside all the other ingredients in the compost, that should be a very good fertiliser. Of course, that wouldn’t scale beyond the vegetable beds. I don’t fertilise the fruit trees or anywhere else in the yard. Fortunately, the soil here seems good enough to support healthy trees.

Aren’t you in north western Melbourne Simon? You’re on Volcanic dirt there, mineral content usually very good. Blessed on an Australia wide context.

That article is 100 per cent correct. I’m an organic farmer and it is completely feasible to get similar nutritional status by using minerals. Here’s the kicker through; those inputs are highly energy intensive. The whole point of good organic soil is to partly overcome natural limits placed by underlying geology and climate. But industrial Ag can override all these limits with the brute power of fossil fuels, constant protection from chemicals and boosted through mined goodies. But what happens when these powerful forces become more expensive?

That’s what organic agriculture is all about, limiting off farm inputs. Although I must say I’m often at odds with organic organisations, like most western institutions they tend towards dogma that loses sight of the original purpose in a mountain of bureaucracy. Some of the rules are just downright silly these days

The proper use of fossil fuels in my opinion actually should be remineralising our soils, especially with more trace minerals that aren’t being replaced.

Australia has actually been ‘powered up’ biologically in some ways since colonisation because we have spread so much phosphate and calcium that was in short supply here of which tonnes and tonnes of the former is now locked up waiting to be dug up and used by biology.

Skip – I’m in the south west, near the Werribee river. Soils seem pretty good here.

Are you familiar with Elaine Ingham and her idea that soil nutrients can be released by boosting microbial activity? I’d be curious to get your thoughts on whether that approach is valid, especially at scale.

On a related note, do you know of any cheap way to test nutrient content in homegrown produce? I’d be curious to get some testing done on mine but the lab testing is bloody expensive, about $500 a pop.

“Are you familiar with Elaine Ingham and her idea that soil nutrients can be released by boosting microbial activity?”

This may be connected to the Indigenous concept of singing up the land. Wilber’s quadrants empower by revealing cultural blind spots that can be explored and capitalised once brought to light.

Skip –

“Who said markets were rational?”

Value is determined by what people need to acquire long-term peace, health and happiness. Price is dependant on what people happen to want. We’ve been taught that those two are the same. In reality, of course, there is usually a gap and it’s getting bigger.

Removing the gap between the two is a pragmatic rationality. Neither capitalism nor communism necessarily provides that. But what could?

Yeah microbes can use a sort of jackhammer to unlock things that have been bound up, but from my experience biology can’t overcome geology if the raw materials aren’t there. There are some in the biodynamic movement who think it can via alchemical processes, so who knows what is possible.

I use a lab in Melbourne called SWEP for most things, soil and tissue analysis mostly. A tissue analysis will cost about $130. It will give you good information about what is being taken up but won’t give you an exact read out on what is in the end product, and as you’ve obviously found that is a more expensive endeavour. The cheapest way is probably how it tastes!

Jinasiri – makes sense. It seems most traditional agricultural practices ended up matching what we now know from science, for example, the use of nitrogen fixing crops planted between primary crops to enrich the soil.

Skip – I’ve read that in biodynamic literature, the idea that the plant creates the soil not the other way around. I believe I saw an example of that here.

There’s section of my yard near the back corner of the house that I had neglected. There was a concrete pathway there which got overgrown with buffalo grass. I’d forgotten all about the concrete and was just mowing it as normal. Then, I decided I wanted to plant something there. When the shovel hit the concrete, I remembered about the pathway. What was fascinating, though, was that there was a good 2-3 inches of soil on top of the concrete and that had developed in no more than three years (probably only two). This is an area where there is no organic matter falling on the ground. So, where did that soil come from? Seems to me that the grass “created” it.

Hi Simon,

You’ve had me considering Dr Ingham’s work, and my best guess is that the work comes at the same problem – availability of a diverse range of minerals for the soil life and plants to feed upon – from a different perspective. But it essentially resolves the same issue. Please hang with me whilst I attempt to explain…

If a farmer or gardener was to import and then spread around, say compost teas which are themselves inoculated with a specific soil biology, well that’s just importing new minerals via a different route. All that diverse soil life won’t have identical chemistry, and so when they die, or are eaten in turn by other soil critters etc. that releases the many different minerals into the soil and the plants are part of that story. It all ends up being a big cycle, but essentially the importing process continues albeit in a different format.

It’s cheaper (from my perspective at least), to bring in the composts, mulches, sands and minerals and let the soil critters sort their own business out at their own time scale. Did you know, just for one example, if you apply lots of nitrogen heavy fertilisers such as err, dynamic lifter, the soil critters will actually lower the soil carbon whilst they have a total party time of the new conditions?

My understanding is that over a long enough period of time, the soils will sort of revert to the average condition for the general area they exist within. The rainfall tends to drive the process in that direction. This is a very complicated subject and I’m wary of hobby horses and easy sounding solutions. Way back in the day, mineral deficiencies in the human population was a very real problem – and that reflects the local soils where the people lived.

Interestingly also the triangular pyramid graphic you depicted tends to reflect the speed at which soil minerals are depleted, with vegetables being the most intensive, and grains the least.

I could talk about this stuff all day long! 🙂 But my basic driving process is to return more from the soils than I take, and by a significant margin as well. That’s an investment in the future.

Cheers

Chris

Hi Simon,

Grasses tend to create good soils, thus why the old timey farmers used to let land lay fallow.

Cheers

Chris

Hi Simon,

Forgot to mention. Your chicken manure is the equivalent of whatever your chickens are eating. From memory you feed them pellets or mash? If you want to super charge your soils I recommend introducing some seeds to their diet – like say adding in the contents from a bag of say Red Hen Blue layer grains. It’s expensive, and the seeds are probably comparatively on the lower quality side of the story due to economic realities, but it’ll make the manure closer to a seed meal based fertiliser. Plants concentrate their minerals in the seeds.

Eventually you’ll have to rotate the crops around the garden.

Cheers

Chris

Jinasiri – pretty simply, get rid of industrial imperial civilisation; capitalism and communism are just masks for the same thing. Doing away with it would pretty aggressively allow for true price discovery. But at what cost? I’m not sure if peace and happiness are what we all really want too. I’m far more inclined to think the masculine energy of our culture craves a contest and the thrill of battle, and our technic economy is in large part a substitute for this.

Simon – yeah no doubt plants create soil, what I’m saying is more the underlying productivity (for food especially) of a locale is determined by the geology and underlying chemistry. In old and leached places like Aus this results in incredibly diversity from trying to deal with these limits, but compared to the mineral content in the prairie of the USA, Canada and Eurasia, or the river valleys of Asia, Aus is an agricultural backwater.

This is what leads traditional Australian diets (and agriculture) to be livestock and meat heavy as the animals can accumulate the minerals in their body from a wide area rather than a limited root zone. Vegetarianism in Australia outside of some very specific areas (or potentially eating things from all over the continent) would result in massive nutritional deficiencies without industrial agriculture, but may be possible without it in the future if we keep spreading minerals everywhere at the rate we are.

Long term, concrete is good for plants too. There’s a bunch of minerals in there just waiting to be broken down and used. I often think this is the Gaia purpose of industrial civilisation. Dig everything up that was locked away in the ground and get it back in the biosphere for everything to use. Like a volcanic eruption; short term destruction, long term benefit.

Chris – Ingham’s reasoning is that adding compost tea is not about the minerals being added but the microorganisms. Her starting assumption is that all the minerals are already present in the soil and the addition of the right kinds of fungi and bacteria will make them available to the plants. Of course, even if that starting assumption is not entirely correct, she could still be mostly right in that soils that are deficient in fungi and bacteria can have the minerals present, but they are not available to the plants. Therefore, adding compost tea would still improve results.

That’s a good point about the chicken feed. Reminds me of the humanure idea. After all, what is the best fed animal in any household? Humans. How many valuable nutrients get flushed down the toilet every day? 🙂

Skip – well, that’s an idea that I hadn’t considered. I wonder if that’s why plants seem to love growing in the cracks in concrete: they’re taking nutrients from it.

It’s a soothing mental balm to all the environmental destruction we do; no matter how big and mighty we think we are, microbes, fungi and plants are looking at all of our built environment (and our bodies) with hungry eyes. Give it enough time, and it will all be food for them. Wait till they start eating skyscrapers.

William Albrecht (his papers from the 50s are worth reading) did some studies looking at cattle eating from roadsides and found that they preferred roadside grass not just because the extra water was making it grow taller, but the grass was actually catching leached nutrition from the road materials.

Skip – completely unrelated, but I happened to catch a news story a couple of days ago about how the Victorian government is failing to mow roadside grass. I guess that’s what happens when you’re bankrupt. Maybe we should send in some cows 😛

The cows? Or the clowns?

Has to be cows. The clowns are too busy sitting in parliament.

Hi Simon,

All very true, but I’d hazard a guess that Dr Ingham’s work isn’t widely applied, because once you put a plough, drill, hoe, trowel or whatever cutting tool floats your boat into the ground, all that work with the soil microbiology will simply die. Dead AF! 🙂 Soil critters rarely appreciate having their homes ripped apart – that’s why digging improves plant growth – the dead microbes release their minerals and so the plants benefit. The ancients noticed this and took the process to it’s logical conclusion – total soil infertility.

Our species loves to dig the soil and has done so for millennia. You simply can’t practice any form of agriculture or gardening without digging. Even the no-dig folks are probably better described as minimal-dig practices. And they bring in huge quantities of stuff to replenish and feed the soils.

Where I reckon that theory would be applicable is in restoring and improving landscapes where the soils remain undisturbed, like forest and grasslands. Applying it to agricultural soils will put you on a course of constant and never ending work. There’d be no end to the work.

There truly is no such thing as a free lunch with this stuff.

However! Here I must state a home truth: If you want the best growing conditions, steal and practice ideas from everyone. Just like how you don’t consume a diet of plants and animals with origins near to your locality, take the best from everywhere. And then test the ideology out for yourself. I’ve been doing that for almost a quarter century – you’d amazed at how much BS gets floated around. Cough, cough: Food forests in Melbourne’s growing conditions. Man the rats the dogs and I’ve killed.

Cheers

Chris

Chris – actually, Ingham specifically targets her idea to farmers who are ploughing the soil. The point of the tea is that you can apply it at scale, where compost would be too expensive to use. The idea is to apply the compost tea directly after ploughing so as to get the fungi and bacteria back into the soil, which should help newly planted crops establish themselves quicker since the soil ecology is already in place for them. I’m pretty sure she only recommends applying the tea a couple of times after ploughing, so the work is minimal.

It’s not really relevant for my circumstances since I’m getting the same result by adding compost to my beds at planting time. That’s the advantage of intensive gardening 😉

On Nutrient Density:

Humans and animals are moving compost bins. Thus there is no necessary conflict between population growth and sustainability. If population growth occurs simultaneous to (1) the drawing and concentration of nutrients from previously untapped sources by way of the mouths of animals and humans and (2) the reinvestment of those nurients into the soil through proper manure processing techniques, then the higher the animal and human population, the richer the soil. As nutrient density increases crop varieties can be adjusted to soak up those nutrients, leading to higher nutrient levels per kilo of food produced as opposed to the death of crops due to nutrients overload.

On Nutrient Uptake:

But even after nutrient density in soil and food are increased, various factors are implicated in relation to nutrient uptake by plants from soil and from food by animals: (1) quality of microbiological life and activity in soils, root systems and digestive tracts, air and water (2) genetics (3) variety of plant and animal species (4) quality of mental energy being produced by animals, humans, spirits and deities. All of the above are mutually influential. (4) is the least understood out of the lot but the most powerful when understood and developed.

The easiest way to describe it to those with materialist biases is in terms of the effect of vibrations upon patterns of crystallization. Like how a thin layer of sand on a metal plate placed on top of a supine amplifier will take on different patterns depending on the type of music being played. The idea is easy to debunk because most don’t have the mental training to put out consistent “vibes” (there are less and less people who are able to maintain consistency and health in their moods). Cultural and psychological stability is essential to environmental rehabilitation, conservation and prosperity. It sounds like hippy woowoo but without good vibes, economies, ecosystems, genepools, natural resources, protein curling patterns, water crystallisation, even the harmonics of molecular spin all degenerate. It’s an enormous cultural blind spot of the modern materialist West.

What needs to be appreciated though is that our mental energy cannot simply be changed by wishful thinking, it must be trained with great discipline, thoughtfulness and precision. The multifarious modalities of spirituality and religion produced by humankind across the long horizon of history can be usefully analysed in this light.

“I’m not sure if peace and happiness are what we all really want too. I’m far more inclined to think the masculine energy of our culture craves a contest and the thrill of battle, and our technic economy is in large part a substitute for this.”

Skip.

I agree that the masculine needs this. But I’d argue that battle should not for the thrill of battle alone as that is merely a short-term outcome which is far outweighed by the pain of long-term remorse, injury, distrust and asset destruction caused by battle if it is done the wrong way for the wrong reasons against the wrong foe. Long-term happiness, peace and freedom are the products of rightfully undertaken battle. Right battles also quell the masculine’s craving for wrong battles thus giving access to short term thrills as well as long-terms happiness. Of course, this is no free lunch as deep martial arts are just that: arts. Difficult to master but worth it.

Jinasiri – that sounds very similar to the philosophy of biodynamics.

There’s a more practical version of the same thing which happens when you start growing your own food because it requires quite a lot of small changes of habit that nevertheless resonate in harmony with a greater meaning. For example, making compost is a system of habits that have a “correct’ pattern that produces the compost. The compost itself is part of a pattern of fertilising the soil which is part of a pattern of growing food. But there’s also a pattern in harvesting and eating the food. You have to “learn” how to do that too including knowing how to cook it and how to structure your life around getting food from the backyard instead of from the supermarket. We tend to think of the physical training required to do all that, but it is first and foremost “mental”.

Hi Simon,

So, are you intending to get the soil test done? I’ve never stumped the cash for a test, and candidly wouldn’t really know where to take a representative sample due to the huge area, but in your situation it could be enlightening?

Cheers

Chris

Yeps. Thus the growing of not just local food but local culture. Noteably local food culture for all times except those most recent was inextricably entwined with local spirituality, local spirits and/or local saints. Once again the Reformation was the beginning of the end of that.

Chris – don’t really see the point in testing. For the price of a single test I can fertilise the beds many times over. Since my home made compost includes material from a variety of sources, it should theoretically contain enough trace elements to prevent problems. However, my understanding is that any shortage of a specific nutrient will show up in stunted plant growth or pathology. So, it should be fairly easy to tell if a deficiency has occurred. As Skip mentioned, there’s also the taste test!

Jinasiri – now we have global food culture. Hence the need to ‘save the planet’.

Jinasiri

Yeah I agree with you in principle regarding long term battles, but I always have the Nietzschean laughter in the back of my mind asking ‘whats makes a right or wrong battle?’ I think it’s a deep underlying feature of our culture to want to constantly fight a sort of battle, we have just found other ways to do it outside the battlefield.

This is due to the love of the struggle and self sacrifice for the greater cause, and our economy insists that almost everyone do this in some way almost every day of their life. The world spanning machine monster and it’s insane demands could only come out of this bizarre feature of our culture, which has been around from the start. The Templars and Hospitallers of the crusades capture everything about it.

It goes back to Simon’s idea that out culture has an implicit death wish. There is a strand that wants to ‘die’ in battle (activism?), to immolate its individual present existence and will in the service of a higher purpose that goes back and forward in time and out and out in space.

Hi Simon,

That’s my take on the world too. For the same bucks, you can buy in trailer loads of stuff, whatever it may be. But as you note, you have to stay alert for trouble and then adjust plans as you go. The future belongs to the nimble and adaptable.

Freakin’ hot today. Fingers crossed we get some rain, lot’s of it.

Cheers

Chris

Skip. Is there anything you see in Australian culture and history that might point towards an alternative?

Chris – in a way, i’m interested to see if it does happen. Since I have the advantage of being able to go to the supermarket if necessary, I’m curious to see whether a compost-only approach does hit problems at some point.

“I always have the Nietzschean laughter in the back of my mind asking ‘whats makes a right or wrong battle?’ ”

Skip.

Lets’ not assume that we must be limited by the scope of Nietzche’s sanity! I think there is an answer to the question. For now, let’s say battles are of two types: corporeal and spiritual.

Following the Sakyan sage, without claiming to speak on his behalf, I’d call a corporeal battle righteous if it is entered into in defence of self and/or others against immediate violent attack, in accordance with 5 rules:

• no intentional killing

• no stealing.

• no sexual misconduct

• no lies

• no taking drink and/or drugs;

while employing proportional force and treating prisoners humanely, and rejecting hatred of the enemy. This last factor is the spiritual battle to be done simultaneous with the corporeal one.

According to this approach any initiation of violence is unrighteous. Herein there is no doctrine of just war, but there are just individual battles of self-defence. This is valour backed by honour, victory over the Other founded upon mastery of one’s Self. This, I venture, is the best way to win the respect of one’s adversaries and the best route to long-term peace settlements after armistice. Peace can only be won in the long term by the capturing of hearts.

How to avoid boredom after corporeal peace is made? The spiritual battle against greed hatred, fear and stupidity is thrilling when you get into it. The Buddha did say he approved of the killing of anger.

Simon, on the topic of plants creating soil I like the counterintuitive fact that plants predominantly grow out of the air rather than the ground. The primary building block – carbon – doesn’t come from breaking down minerals, it is quite literally extracted from thin air. And then the soil emerges in a large part from the discarded plant matter.

Daniel – good point. Apparently recent research has also found that plants can absorb far more carbon than was previously thought. Seems certain that as carbon increases in the atmosphere, plants will grow faster and larger.

My guess is that it’s not just carbon that plants can capture from the air but other nutrients too. And not just plants but microbes.

It is also quite possible that good vibes created through proper training in ethical restraint, generosity and universal care attract certain types of plant and microbial communities and promote certain lines of microbial and plant behaviour. Both of which may improve soil nutrient density, nutrient retention and vitality. This may be a powerful tool, free and available to everyone (who trains) just waiting for implementation and research.

Well, it’s definitely true that some plants can capture nitrogen. Once again, we can see that the old timers figured this out by trial and error because it was noticed that some plants grew better together even though nobody knew the exact mechanism involved.