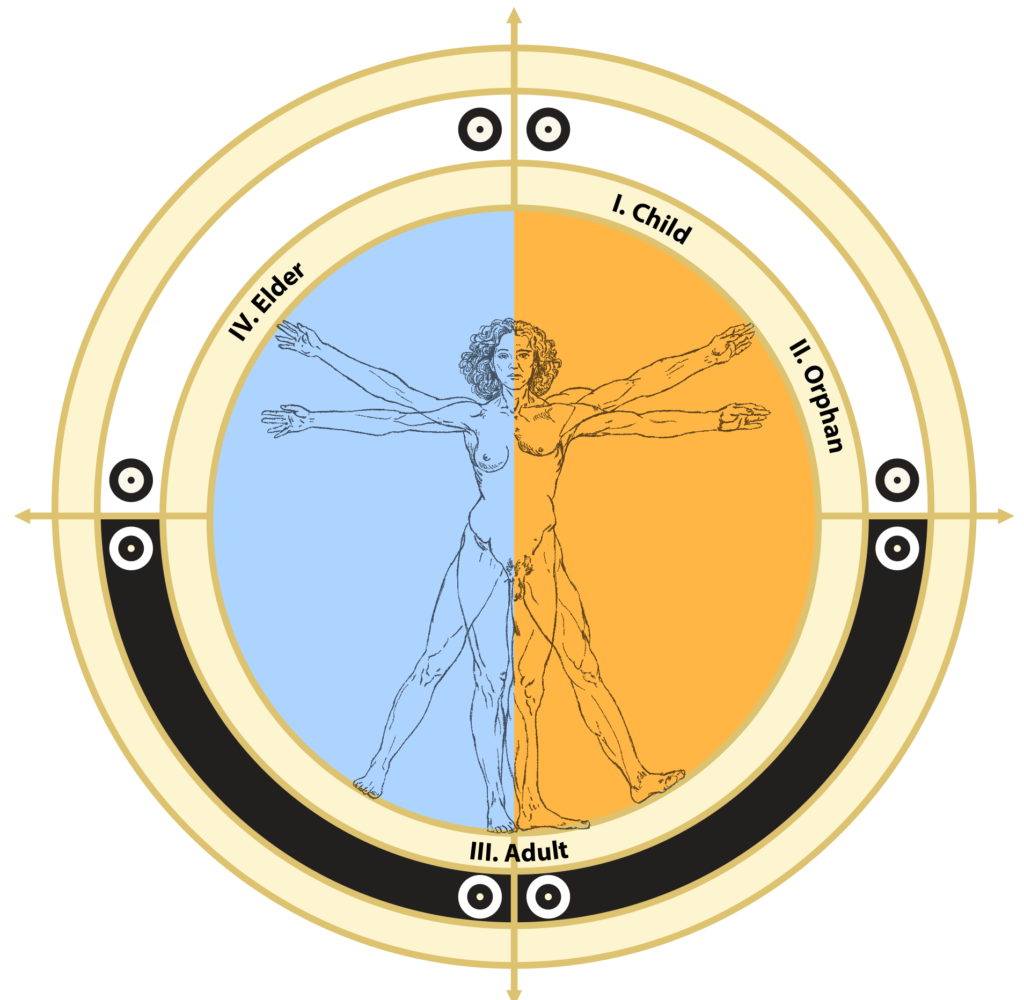

Archetypology is a holistic framework for understanding human growth and development. Taking inspiration from both Jungian and humanistic psychology, the model posits four primary archetypes: the Child, the Orphan, the Adult, and the Elder. Together, these constitute the main qualitative stages of life’s journey.

Nobody would deny that childhood is qualitatively distinct from adulthood or adolescence from senescence. In archetypology, we analyse those qualitative differences according to three broad categories of biological, socio-cultural, and higher esoteric. These form the domains of our identity.

Our biological identity refers to our physical properties, such as eye, hair, and skin colour, height, body type, etc. Our socio-cultural identity refers to our membership of societal institutions, our career, our class position, and our political and religious affiliations. The higher esoteric refers to our psychological attributes (introvert-extrovert, etc.) as well as what we might call our metaphysical beliefs about the world. Each archetype has a specific set of qualities in each of these domains of identity over and above the details of any individual life. For example, without knowing anything about the individual in question, we can say with confidence that their development during the Child phase of life contained little growth in their metaphysical belief structure (the higher esoteric domain of identity). That aspect of our character begins in earnest during the Orphan archetype. We can draw similar conclusions about character development during the other archetypal phases.

Beginning with the premise that the archetypes are qualitatively distinct phases of life, it follows logically that we must undergo a metamorphosis to transition between these phases. This sounds complicated, and yet it’s really just common sense. It is uncontroversial to say that puberty is a biological metamorphosis. Before puberty, we have a child’s body. After it, we have an adult body. In between, there must be a transformation. What is true in the biological domain is equally true in the socio-cultural and higher esoteric. The psychoanalysts posit that puberty also comes with the arrival of the ego, an event which has a number of psychological consequences and which also sharply differentiates childhood from adulthood. Meanwhile, anthropology tells us that it is a universal of human culture that there is a socio-cultural metamorphosis that comes around puberty. The child must leave the safety of the family and begin to contribute to the institutions of society. Just as the archetypes themselves are qualitatively distinct, so too is the metamorphosis to transition between them. Each archetypal phase of life begins with a transformation that brings with it distinct challenges that must be overcome.

We see that each archetype has a unique set of qualities, but those qualities are not just inherent in the individual but face outwards and integrate with the broader social and cultural context. This leads into one of the core concepts of archetypology that differentiates it from the Jungian paradigm. Jungian psychology understandably focuses on the inner psychic aspects of the archetypes as present in the imagination or collective unconscious. In archetypology, we call this the esoteric, or inner-facing perspective. We aim to balance this against the exoteric or outward-facing perspective. When we do that, we find that the archetypes are not just components of the psyche or the collective unconscious but have what anthropologists would call a functional purpose. By linking this functional, societal viewpoint with the esoteric, psychological one, archetypology allows an appreciation of the interactions between the two. What we then find is that pathologies in the esoteric domain (“mental illness”) are almost always related to pathologies in the exoteric, social one.

It is the ability to see connections between nominally discrete areas of life that gives archetypology its holistic and integral properties. When we place the archetypes at the centre of analysis, we see clear correspondences between biology, anthropology, psychology, theology, and history. But the correspondences are not just related to scholarly disciplines. As the Jungians discovered, ancient myths are full of archetypes, as are contemporary stories and films. The evidence for the archetypes comes not just from modern scholarship but also ancient wisdom and plain old common sense. Put together, the archetypes then become a way to think about the development of character not just in a psychological sense but in a holistic one that takes into account the full range of human identity.

Because each archetype builds on the one that came before, archetypology is a framework for understanding the growth and development of character over the course of life. This leads to the other major component of the model, which is the process by which growth occurs. When we analyse the nature of that process, we find that it has a great deal in common with the concepts of illness and recovery in modern biology, but also with the pattern of rites, ceremonies, and training seen in many of the spiritual traditions of the world. Even in a purely secular sense, we find that the pattern of growth is “sacred”.

The word sacred means to make holy. The word holy is in turn related to the words wholeness and health. To be in sacred state is to be divided, incomplete, unwhole and unhealthy. A sacred process returns us to wholeness and health. The notion of sacredness also implies a sacrifice. We offer something up, but we get something in return. In modern biological terminology, this is related to the process of adaptation. On the other side of the sacred process, we are better adapted than when we started. As Nietzsche put it, “What doesn’t kill me only makes me stronger”.

The progression of archetypes during the course of life follows this process of growth. The “sacrifice” we make as we transition from one archetype to the next is our old archetypal identity. This identity consists of biological, socio-cultural, and higher esoteric components. We must give that up in order to adopt the new. Thinking again of the Orphan archetype, with the biological changes of puberty, we sacrifice our child’s body and exchange it for that of an adult. We sacrifice the innocence and carefree nature of childhood for the responsibilities of adulthood. Failure to come to terms with the sacrifice can lead to the kinds of psychological pathologies that the psychoanalysts discovered. But the difficulties of the growth process are not limited to the psychological realm. We carry the physical scars of earlier archetypal phases into the later ones. The same is true in the socio-cultural realm, e.g., a criminal record stays with us for the rest of our lives. The sacred growth process makes holy, whole, and healthy in all aspects of identity.

In archetypology, we call this growth process the cycle-ending-in-transcendence, representing the fact that the successful negotiation of a metamorphosis allows us to transcend that which went before. Again, this transcendence can be said to occur across the domains of identity. All of us have experience the physical healing process as we have navigated injury and illness. Psychoanalysis did much to highlight the mental healing process in the 20th century. Meanwhile, it was also in the 20th century that the anthropologist Arnold van Gennep discovered that every society navigates the sacred by implementing what he called rites of passage, a kind of social healing process. What we note in archetypology is that all of these are manifestations of the same pattern: the cycle-ending-in-transcendence. Over the course of life, we may go through many such cycles, but the archetypes represent the major cycles that everybody must go through and that seemingly every culture recognises.

Putting it all together, we can summarise the core concepts of archetypology as follows:-

- Archetype: a discrete phase of life consisting of qualitatively distinct properties of character formation. The four primary archetypes are Child, Orphan, Adult, and Elder

- Character: the dynamic interaction between the three primary identities of biological, socio-cultural, and higher esoteric

- Identity: a process that oscillates between the exoteric and esoteric poles, driven by the inner needs and desires of the individual and the collective influence of environment, society, and any higher powers that one believes in

- The cycle-ending-in-transcendence: the process by which we incorporate something new into ourselves, most notably a new archetypal identity

Although the number of core concepts in archetypology is small, the combinatorial complexity of the model is not. Consider that the three domains of identity each have an exoteric and esoteric aspect. That gives us six combinations. Since each of these resonates differently across the four primary archetypes, that gives us 24 combinations. When we acknowledge that each of these resonates differently according to sex (male-female), we get 48 combinations. That’s just the beginning. Even though archetypology focuses on abstract concepts, the complexity of the model quickly becomes apparent. The advantage of archetypology is that it can make this combinatorial complexity conceivable without getting bogged down in endless detail. Archetypology is a map, and, like any good map, it outlines the terrain and allows us to zoom in on the parts as we desire.

To summarise, archetypology aims to account for the growth and development that we each must go through over the course of our lives. With archetypology, we follow the conjecture of the great Canadian literary critic, Northrop Frye, who speculated that the recurrent pattern found in myths and stories could provide a unifying framework for the humanities and thereby for human nature in general. The cycle-ending-in-transcendence is the name we give to the pattern that Frye was referring to. It is based on the hero’s journey formula discovered by comparative mythologist Joseph Campbell and also the rites of passage structure discovered by the aforementioned Arnold van Gennep.

Archetypology posits that the archetypal phases of life follow this same cycle. Gregory Bateson once wrote that humans think in stories. With archetypology, we go one step further and say that humans are stories.

Sound interesting? A full introduction to archetypology is now available.