The Canadian literary critic Northrop Frye believed that you could tell a lot about a culture from the types of stories it told itself. If I’m correct in saying that Adolescence has accidentally created a new type of story, then we might expect that story to be relevant to larger cultural trends in the modern West. There is ample reason to think that’s the case because the transition between the Child and Orphan phases of life, which the drama of Adolescence focuses on, has undergone a fairly radical change in our culture in the last hundred or so years, albeit one that has antecedents in the centuries leading up to the 20th.

To understand those changes, let’s begin with the most fundamental of all relationships, that between Parent and Child.

The primacy of this relationship is a universal of human culture. However, what we find in Western culture, and this goes all the way back to late medieval times, is an unusual emphasis on the Child-Parent pairing. The nuclear family paradigm, where the household consists of only parents and children, has become more and more predominant since around the 16th century, reaching its apotheosis in the post-war years. Prior to that, extended families were the norm.

Thus, the expectation that Parents should play a dominant role in the lives of their Child goes back to the late medieval era. Like with most philosophical ideas, however, it received its “official” form well after it was already a mostly unconscious belief of the culture. The “new” educational theories that made the Parent primarily responsible for the upbringing of their Child arrived in 18th century. The almost universal prevalence of the nuclear family paradigm that has taken hold in the post-war years in the West is a culmination of this trend.

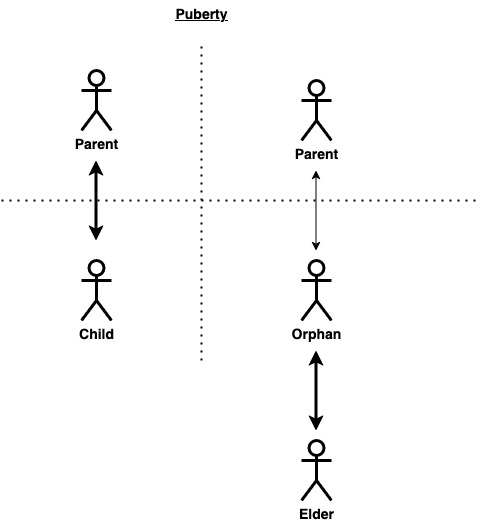

The upshot of all this is the role of the Parent has had an outsized importance in Western culture for a very long time. We might hypothesise that this is due to the deprecation of the role which, in most cultures, becomes predominant after the Child archetypal phase of life has come to an end and the individual transitions into the Orphan (i.e. adolescence). Speaking in general terms, and noting that there are all kinds of cultural variations on the pattern, what we see in every culture is that the Child-Parent relationship gives way to the Orphan-Elder one. This occurs around the time that the Child reaches puberty. At this time, the Parents are supposed to step back from their dominant role and hand over to the Elder. We can diagram this as follows:-

Obviously, we always remain the children of our parents, even if we become estranged from them. What the diagram is intending to convey is that the Orphan-Elder relationship becomes dominant after puberty. Parents must step back and allow their children to become independent. Children must leave the safety of the family unit and join the institutions of wider society. The representatives of those institutions are the archetypal Elders. It is their job to initiate the Orphan into the institution and provide training and guidance with the intention of making them fully-fledged members.

It is worth pointing out that there has traditionally been a sharp distinction between the sexes on how the Orphan separation from the Parents plays out. Women have arguably had the more definitive break because the most common pattern historically has been for them to marry shortly after puberty and be inducted into the family of their husband. In times before modern communication technology, this may have entailed a complete break with the Parents if the young woman needed to leave the town or village of her birth.

In any case, the woman is inducted into the family of her husband and we say that the Elder who initiates her is the matriarch of the husband’s family, either a mother-in-law or grandmother-in-law. Since women’s place was the home, the initiation included learning how to manage and contribute to the household, which, in most cultures, is an important place of economic production (the word economy comes from the Greek oikos, which means “house”).

Now, it’s important to realise that the break with the parents that the young woman goes through is very abrupt. There is time to mentally and emotionally prepare for it since marriages are usually arranged well in advance, but once the ceremony is over, the bride is no longer a part of her parent’s household. That phase of life is now over.

This sharp break with the Child phase of life also characterises the traditional initiation for young men. In hunter-gatherer tribes, the boy is carried off by the men of the tribe for an initiation that lasts many months. We see the same pattern in warrior-based societies. For example, in ancient Crete, the boy was “abducted” while sleeping and taken off for military training. The physical hardships, scarring, tattooing, and other practices carried out during initiation also serve the purpose of demarcating the new phase of life i.e. the Orphan.

The symbolism of being snatched from a mother’s arms or kidnapped from the parents’ household is clear. Childhood is over. The dominance of the Child-Parent relationship is over. The boy or girl is no longer just a member of their family; they are a member of the wider society.

Western culture never seems to have had intense practices such as those just mentioned, and this is no doubt due to the civilising influence of Greece and Rome channeled through the Catholic Church. In particular, Rome’s emphasis on the family seems to have passed down through the Dark Ages and into the feudal system. As a result, both feudal initiation and induction into the Church were marked by relatively tame ceremonial means.

The increased emphasis on the Child-Parent pairing began with the breakdown of the feudal system and the rise of capitalism. This led to a shift away from extended families and towards nuclear ones, especially in the towns and cities where proto-capitalism was hitting its stride. Capitalism’s emphasis on personal effort and work was matched by the Protestant belief in the single individual before God. This led to a focus on personal responsibility that was expected to be inculcated by Parents.

Nevertheless, during this time, the church still functioned as the main institution that provided both a sense of community and also a set of formal initiation rites that were given to individuals to mark the various stages of life, including the transition from Child to Orphan. Although the economic sphere was liberalising, the church provided a sense of continuity with the older traditions.

That lasted up until the 19th century, when the state pretty much went to war against the church in most Western nations. The church had its educational, administrative, legal, and welfare activities removed. Marriage and divorce became state matters. Education was now dictated by the state bureaucracy rather than the church. The welfare state took over from church charity. In general, the church and state were separated, always at the church’s expense.

Whatever else we want to say about that, it severely reduced the importance of arguably the last recognisable Elder role in Western culture: the priest/bishop/pope. What also disappeared were the rites of the church which marked the different phases of life. As church attendance fell off a cliff in the post-war years, we find ourselves without any ceremonial markers of the phases of life or Elders to perform them. The state is run as a technocratic institution according to bureaucratic rules and we are granted our “rights” based on such criteria.

In short, the experts have replaced the Elders. The state replaced all the functions of the church and swapped the priest for the technocrat. The “initiation” that we now receive is into the institutions of the state. But just like an expert bears no real resemblance to the archetype of the Elder, bureaucratic rules bear no resemblance to anything that has traditionally been called initiation. The closest thing we get to a form of initiation in modern Western society is the military. We might hypothesise that the reason so many men eagerly signed up to serve Napoleon or in the world wars was because the army offered a “real” initiation in a society where it had otherwise disappeared.

With that brief overview of the historical and cultural background, we can now return to the Netflix series Adolescence and better understand the way in which it portrays the “initiation” of the 13-year-old Jamie. Jamie is on the threshold between childhood and adolescence. He’s exactly the age at which, in tribal or warrior-based societies, he might be plucked from his bed and carried off for initiation. But that’s exactly how Adolescence begins! At the start of the first episode, Jamie and his family are asleep in bed when the police break down the door. Since the police are heavily armed, they even look like warriors come to haul the young boy off.

Of course, Adolescence is not presenting this as a normal initiation for a young man in modern Western culture. On the contrary, all of this is pathological. Jamie is going to receive the initiation of a criminal. The underlying belief of modern Western culture is that adolescence should proceed “naturally”, an idea that goes back to Rousseau and the Romantics. Jamie is going to be denied a “natural” adolescence.

Thus, Adolescence presents a strange combination of archetypal tropes alongside modern realism. Jamie is going to receive a kind of initiation, not at the hands of tribal Elders, but the technocrats who run the modern state apparatus. These technocrats include the teachers at the school that Jamie attends, the police, and, most importantly, the psychologist in episode 3. These are all professionals belonging to the class of experts who run the modern state which disintermediated the church about a hundred and fifty years ago. They are the modern equivalent of the Elder archetype, and it is therefore fitting that Eddie must yield his parental authority to them because his son has come of age.

In symbolic terms, Adolescence provides us with a classic Orphan initiation. This is actually very common in modern storytelling. Curiously, even though modern Western society has all but gotten rid of formal initiation practices, whenever we represent those practices in story form, everybody automatically understands them. When Luke Skywalker is initiated by Obi-Wan in Star Wars, it’s perfectly understandable that his parents and aunt and uncle are dead and that he can trust his Elder. When Neo takes the red pill in order to receive initiation from Morpheus, we don’t bat an eyelid at the fact that he is leaving his old world behind forever. Somewhere deep down in our unconscious mind, we understand that this is the way a “real” initiation must be done.

That is also what is happening to Jamie in Adolescence. By the end of episode 4, he has been away from his family for more than a year and there is no prospect of him returning. We might say that he is in the middle of his initiation. We see that most clearly in episode 3. The psychologist is going to teach Jamie a lesson of sorts by getting him to confess to his crime.

The use of the psychologist trope is perfectly consonant with the modern technocracy that arose in the last 150 years. But like most of the sciences, psychoanalysis was not originally an extension of state power. It began as a small, private group of enthusiasts in Vienna led, of course, by Freud. It is no coincidence that Freud and Jung had been trained in medicine. What they realised was that their patients had nothing physically wrong with them. That led to the search for psychological explanations.

I don’t know if it ever occurred to Freud and Jung how similar psychoanalytic practice was to the sacrament of confession that the Catholic Church had been conducting for millennia. Freud even stayed out of sight of the patient to encourage free expression, just as the confessional booth gives the confessor the feeling of anonymity. The Christian priest was a trusted Elder who could be relied upon to provide a listening ear and wise counsel. By the start of the 20th century, however, the elites of Europe could no longer take the priest seriously. But they could take a psychoanalyst seriously because he was a “scientist”. Freud and Jung inadvertently became Elders of the new religion of science.

Much like all the other sciences, psychoanalysis inevitably got sucked up into the vast technocratic apparatus that runs the modern state. Indeed, it seems that governments these days are almost as eager to pump money into “mental health” as they are into the health system more broadly. Psychology is now the domain of the expert, not the enthusiast. Thus, the psychologist in episode 3 of Adolescence does not represent herself as a private citizen offering a service, as did Freud and Jung, but as an employee of the state doing her job of greasing the wheels of justice. Her extraction of a confession from Jamie is done with that end in mind, and it is here that the contrast between the new and the old Elders of Western culture becomes most stark.

The Catholic priest has always been bound to keep the contents of the confessional booth a secret. Even if the confessor claims to have committed murder, the priest must not disclose this information to anybody else. This is called the Seal of Confession. Violating the seal is a serious offence usually resulting in excommunication. In this, we get a glimpse of the true nature of the Elder role, at least as it was intended to be practised in the Catholic tradition. It is primarily a personal relationship which places the conscience of the individual above the interests of the state. It’s no surprise that this should be the case. After all, the story of Jesus’ crucifixion is the story of personal sacrifice predominating over an unjust application of state power.

This contrast is why the final scene of episode 3 is genuinely dreadful. Jamie realises he’s been played by the psychologist. He asks her whether she actually likes him as a person. She answers by explaining that she is a professional. However imperfectly it might have been executed, what the Christian priest offered was the kind of care that Jamie is talking about. More broadly, that is what the Elder always offers the Orphan. Proper initiation is something more than a transaction or a bureaucratic rule. That is why the professional, the technocrat, and the expert can never be a true Elder.

Thus, modern Western culture no longer offers real initiation or real Elders. The family remains as the only institution that offers unconditional acceptance, at least in theory. In practice, one of the more important roles that the church used to play was as a kind of backup in the case of family breakdown, an institution that offered unconditional acceptance to those who could find it nowhere else. We got rid of that and now we have only the state. Although the state theoretically guarantees certain rights, those rights have a habit of disappearing when they are needed most. We saw that in the last few years.

And this is where Adolescence achieves a meta meaning that I believe the creators of the show did not intend. It is actually an accurate representation of the unconscious anxiety that accompanies the transition from Child to Orphan in modern Western culture. Eddie is going to lose his son. That’s what every Parent must do when their Child is an Orphan ready for initiation. But in the modern West, what that means is that he must hand Jamie over to the technocrats of the state – the teachers, the police, and the psychologist. However much the state tries to reassure us that it is full of compassion and will keep us “safe”, we know it’s not really true. The 20th century showed us what the state is capable of. A bureaucracy is just a machine. Eddie is the Parent who must sit back and watch his son disappear into that machine.

Hi Simon,

Intriguing, but you would have noticed that plenty of people are turning back to traditional religions? Toynbee and Spengler may have dubbed this movement the second religiosity, and it marks a serious moment of decline in western culture (the disparagement in that instance relates to the experts and government of course).

Dude, have you ever met an expert and/or government official who fostered genuine community?

Maybe I’m cynical, but the whole push for the err, how did you put it again, nuclear family significance, appears to be the old divide and conquer move. People in isolation are much more easily taken out, than if they have strong and established social connections.

Oh, by the way, speaking of ‘staying apart keeps us together’, did you spot this?: Emails show Melbourne COVID curfew was not based on health advice, opposition says

Cheers

Chris

Chris – I don’t know anybody who’s become religious. All the statistics on religious attendance have shown a steady decline since the end of WW2 with no sign of reversal. If the second religiosity is here, it’s doing a very good job of disguising itself.

Think about the functions that the state deliberately took over from the church. Once upon a time, people in economic strife would have turned to the church for charity. Now they get welfare from the government. Meanwhile, all this money for “mental health” means that people are more likely to seek counselling from a professional rather than a priest. All roads lead back to the state.

You mean Dictator Dan didn’t consult the oracle before announcing curfews? No wonder Melbourne was cursed!

I think there’s another factor at work that makes me profoundly uncomfortable: Adolescence shows the entire process of growing up as pathological. The initiation is only happening because the child has become a murderer, among the most heinous people. This is the only “realistic” portrayal I’ve seen in contemporary culture about the transition from child to orphan to adult. Star Wars, Harry Potter, the Matrix, all the other examples are clearly set in fantasy worlds. It says something quite disturbing about the fact that making the child a murderer is what is necessary in order to make the transition from child to orphan make sense in the “real world”.

I find this fascinating, because of one of the implications this has: namely that our society sees the process of growing up as inherently pathological. The rise of the Devouring Mother then would seem to be a symptom, and not a cause; the way that the older Boomers here in Canada (I don’t know the Australian cultural context well enough to say if it’s the same) are still unable to let go of the counterculture and their revolt against their parents is a similar symptom of the same problem. Somehow, our culture has become unable to admit that we have a lifecycle, and that the Child must become the Orphan who must become the Adult who must become the Elder. Somewhere around the 1960s, everyone started to get stuck at the stage they were in.

We have no Elders because the people who should be the Elders are stuck as Adults; we have no proper Adults because the people who should be the Adults are stuck as Orphans; we have no proper Orphans because the people who should be the Orphans are stuck as Children.

Anonymoose – true. We no longer have any marker of the Child to Orphan transition. Marriage used to be the the definitive marker of the Orphan to Adult, but the meaning of marriage has disappeared now that you can divorce at any time. There is no Elder role left, ergo there is no Adult to Elder transition. That just leaves the Elder to Ancestor transition (i.e. death) and, as your fellow Canadian, Stephen Jenkinson, has pointed out so eloquently, we don’t know how to deal with that either. Somehow, we’ve gotten rid of all the societal markers of the archetypal transitions.

I think this goes back at least to the Romantics, who had the idea that civilisation itself was the problem and that the thing to do was to go back to “nature”. The hippie boomers believed much the same thing. I think the same idea underlies the apocalypse fantasies around climate change as well as the anti-Western, anti-colonial, and anti-white agendas. For more than two centuries now, a sizeable chunk of the western intelligentsia has seen western civilisation specifically, and civilisation itself more broadly, as inherently evil.

The Romantics had the idea of the “child of nature” who owed all his strength to the fact that he was not initiated into wicked civilisation. A prime example is the heroes of Richard Wagner. Siegfried’s great strength is that he grew up in the woods away from civilisation. He gets brought undone by the civilised schemer, Hagen.

Interestingly, Wagner borrowed heavily from the medieval myths of Europe, and we can find this idea of the purity of “nature” vs the evil of civilisation even there. For example, in the original myth of Parsifal, Parsifal’s mother raises him in the forest in the hope that he doesn’t get corrupted by the affairs of men. But when he comes of age (Child to Orphan transition), he goes off to become a knight and receives initiation from Gurnemanz. I think the medieval myths were really representing the Child to Orphan transition which, traditionally, was the removal of the boy from his mother and his subsequent initiation into society. Thus, the Romantics’ denial of civilisation is the denial of the Child to Orphan transition and the boy gets stuck with his mother, who now becomes the Devouring Mother by default.