I deleted my twitter account a few years ago but every now and again I’ll end up on twitter by following a link I find somewhere on my internet travels. People who have visited twitter know that it has a “What’s happening” section on the right hand side which is mostly filled with paid propaganda. You know the kind of thing – “Hollywood celebrities reveal why eating bugs is super cool”; “10 reasons why using air-conditioning is worse than kicking puppies”. But the section also includes trending words and phrases and so it was another “coincidence” last weekend when I happened to be on twitter and noticed that the phrase “Patrick White” was trending after I’d just finished writing a couple of long blog posts about him. I decided to click and see what people were saying.

It turned out that some celebrity with lots of followers had asked for recommendations to Australian literature and numerous people had responded by telling her to check out Patrick White. What was particularly interesting, though, was that the recommendations were almost universally something like this: “I don’t understand/like Patrick White. But he won a Nobel Prize, so he must be good.”

This is yet another example of an Appeal to Authority. Rather than recommend an Australian author that they actually like, people felt it more appropriate to recommend one they didn’t like but who had been formally recognised by the authorities. This was a dynamic White was well aware of and apparently he had strongly considered rejecting the Nobel Prize for the exact reason that he didn’t want to become one of those writers that people read just because he was officially certified. No doubt he is turning in his grave as we speak.

In any case, the responses on twitter didn’t surprise me because I had noticed the same problem in reading some of the longer reviews of White. Most people don’t understand his books and if you don’t understand what he is doing you can’t appreciate it. White was doing things in his books that hadn’t been done before. Unless you know what those things are, you can’t parse the book and grasp the bigger picture.

That is what I was getting at in my recent post about White’s book, Voss. I barely even scratched the surface of interpreting the themes in the novel itself. Rather, I was trying to provide a high level understanding of how to parse the book. This requires some knowledge of the theory of stories as well as a knowledge of some classic literature and, arguably, some Jungian theory too. Without these, it’s not possible to understand White in the same way that you can’t just start learning calculus one day unless you have a solid foundation in geometry, trigonometry and algebra.

The reference to maths here is directly relevant to another important development in modern thought which is Quantum Mechanics. My maths is nowhere near good enough to validate this claim, but I’ve heard it said that the mathematics of Quantum Mechanics is quite simple and elegant once you get your head around it. Thus, even though the concepts of Quantum Mechanics violate our common sense understanding of the world, the maths is quite straightforward. I think the same is true of White. It took me a long time to unpack Voss, but once I did I could see the elegance of the underlying structure and, crucially, that the structure built on top of what was already there historically. White did not throw all the rules away, he added to them and extended them in the same way that Quantum Mechanics built on and extended the science of physics. These developments were not the arbitrary whimsies of people with too much time on their hands. They were responses to the larger historical and social context.

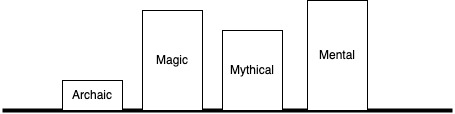

Of course, both White and Quantum Mechanics are not understood in the general culture and this is where Gebser and systems thinking come into the picture because they both believed that what was really going on was that we had reached the end of the road with the old ways of thinking and it was time to move to a new paradigm. That new paradigm is not a break with the past but a response to it. The 20th century showed exactly what happens when you try and break with the past and declare a Year 0 (I suppose the French Revolution had already foreshadowed this lesson). Spoiler alert: everything goes to hell. We don’t need to reject the old thinking. On the contrary, it’s only through an understanding of that old thinking that you can follow the path into the new because the new came out of the old.

What we are talking about here is education. To understand White, you need a certain education that you bring to the task in the same way that you need an education in maths and science to grapple with Quantum Mechanics. If we assume, with Gebser, that both White and Quantum Mechanics represent a new form of consciousness, it follows that a new kind of education might be required to bring that about. What might that education look like? Before we try and answer that, let’s do a lightning history lesson on the modern education system.

Viewed in historical terms, our current system of education is both very new and also very unusual. In terms of years spent in education, we are the most educated society in history by a long way. No other large societies achieved universal education beyond elementary level. Even as recent as the pre-war years, the majority of students in western countries did not finish high school and only a tiny minority would go on to higher education. Nowadays, a significant fraction of students in western countries will go on to university. That’s historically unprecedented.

The current system of education in western countries was based on the Prussian model introduced by Frederick the Great in the 18th century. Prussia achieved a version of universal education well ahead of other western nations. Even the United States sent envoys to Prussia in the 19th century to learn about the education system there in order to set up something similar in the US. Meanwhile, Britain and France did not achieve universal education until the 1880s.

No doubt there were many good intentions and high ideals in relation to the idea of universal education. But, as G K Chesterton pointed out, the two main drivers for universal education in most countries were the fact that child unemployment had become widespread due to increased productivity from industrialisation and automation. Children who were out of work would often turn to crime or get themselves into other kinds of trouble and so universal education became a way to get them off the street.

The second driver was the desire by the State to get the Church out of education. This was a long battle and was a big part of the reason why Britain and France were behind Germany. Germany would later have its own fight with the Catholic Church in what was called the Kulturkampf (yep, the culture wars are nothing new). Of course, the State eventually won the battle and the rest, as they say, is history.

Another big driver for the rollout of universal education was nationalism and we shouldn’t forget the role that universal education played in creating the conditions that led to the world wars. With the universalising influence of religion removed from the picture, states were free to push nationalist dogma in the schools. To take just one small example, it’s only in recent decades that the Australian national anthem is no longer sung at the start of the week in schools. That was a relic of the nationalist agenda tied up with universal education.

The Prussian system of education, in line with Prussian culture at the time, was by modern standards unbelievably rigid. Rote learning was the norm and strict discipline was maintained. Again, this is another element of modern education that has only very recently disappeared. The use of physical punishments such as the strap and the cane were all par for the course until recent decades. Teachers quite literally beat the education into you in the old system.

The Prussian system was partly inspired by the Chinese system that goes all the way back to Confucius. Europeans thinkers such as Voltaire had just started to learn about Chinese culture and history and the meritocratic system of education that had been instituted in China all those millennia ago appealed to the thinkers of the 18th century. That system was never designed for universal education. It’s purpose was to educate bureaucrats in the tasks required of them in the administration of the State. Exams were there to determine who got a job in the civil service. Since only a small fraction of the public could become bureaucrats, it made no sense to educate them as such but that’s what European countries accidentally ended up doing by rolling out universal education in the late 19th century. Is part of the reason why we have all these bureaucracies these days simply because we educated so many people in a system designed to produce bureaucrats?

Within Gebser’s model, this all fits into the Mental Consciousness. The bureaucracy is, in fact, the ideal organisational structure for that way of thinking. It makes everything explicit, concrete and rule-based. It’s no coincidence that a system partly designed by Confucius would work because, according to Gebser, he was the leading exponent of the Mental Consciousness in ancient China in the same way that Plato, Socrates and Aristotle were for the West. Thus, the modern education system also had its exponents among the intellectuals such as Fichte, Humboldt and Voltaire.

Let’s summarise.

The modern education system in the west is a very recent development by historical timeframes. It emerged via a conglomeration of social, economic and political factors. It was based on a style of education aimed at training bureaucrats for the boring, mundane work administering the state but got rolled out to everybody in western societies as universal education became the norm. This style of education fits into the Mental Consciousness as seen in the strict, rule-abiding discipline that was followed.

Here’s the problem from a Gebserian point of view. At exactly the same time we were rolling out a form of education based on Mental Consciousness, the Integral Consciousness was starting to appear. The modern education system was already out of date by the time it started. If this is true, it raises the question of what type of education is required for the Integral Consciousness. Here is one guess at an answer.

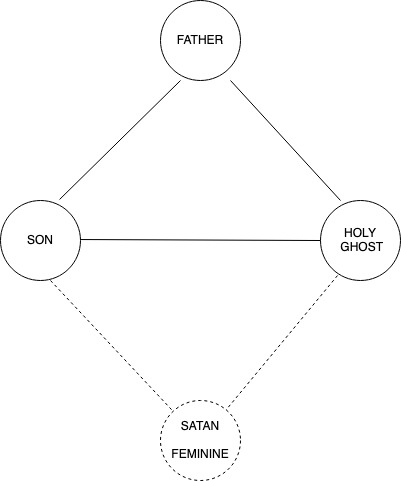

Let’s take Quantum Mechanics and Patrick White as our starting point and let’s assume, as I believe, that they are both paradigm examples of the Integral Consciousness. As we are trying to teach Integral Consciousness, we start there. The first thing to note is that an Integral understanding of both is only possible if you grasp the historical precedents that led to them. In the case of White’s Voss, the main historical precedents are Goethe’s Faust and Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. But in order to understand Faust, you must have read the Book of Job and in order to under Pride and Prejudice you probably need to know Romeo and Juliet as a bare minimum. You also need a basic technical understanding of literature and storytelling and modern psychology. Based on all this, we can surmise the following syllabus; the minimum set of requirements to parse what White was doing in Voss:

The Book of Job

Faust

Romeo and Juliet

Pride and Prejudice

The Hero’s Journey and 3 Act Story Structure

Basic Freudian and Jungian psychology

We could do a similar thing for Quantum Mechanics. I’m not in a position to write it, but I think it would look something like this:

Pythagoras

Euclid

Newton

Einstein

Algebra

Trigonometry

Calculus

Note that these syllabi also entail a history lesson as the locating of things in historical context is crucial to the Integral Consciousness. Thus, rather than just teach the Pythagoras theorem and how to use it, you have to understand what problems Pythagoras was trying to solve. Same with Newton. Same with Einstein. In doing so, you place Quantum Mechanics in its historical context and we give it meaning as the result of real people grappling with real issues.

This raises the question also for the student: what issues are you grappling with? Why are you learning Quantum Mechanics? Why are you reading Patrick White? Are you doing it just to get good grades which you think will lead to a well-paying job? Do you need it for some practical engineering problem? Are you trying impress your friends and family? Are you trying to figure out the meaning of life or the secrets of the universe? Are you just curious? All these and more are valid reasons and by making them explicit you also put yourself into historical perspective. Pythagoras, for example, would have thought it pathetic to learn something just to impress others. That was called sophistry back in the day. For the Pythagoreans, there was no vocational education, there was only spiritual education. Thus, to remove the Pythagoras theorem from its spiritual/historical context is to miss the most interesting bits.

All of this might sound impractical. But without this understanding, what happens is that people perceive writers like Patrick White as “breaking the rules”. Then everybody decides that the way to write modern literature is to break all the rules and churn out stream of consciousness vomiting the contents of their mind onto the page and calling it high art. Thus, what gets called modern literature explicitly rejects any form of structure. It throws away all the old rules and replaces them with, well, nothing.

That is not what Patrick White did. In many respects, he was a very disciplined writer who followed the rules to the letter. He didn’t throw away the rules, he built on top of them. That is an incredibly important distinction because everywhere in the modern world we see the old rules being abandoned. This is, in fact, exactly what our modern elites do all the time in all areas of life, not just the arts. That’s how we got the unprecedented idea of lockdowns and the equally impossible idea of a vaccine stopping a respiratory virus. There was never any evidence these would work; no foundation in history or science. They just got wished into existence while all the old rules of public health were thrown in the bin.

The mindset that encourages such things to happen is the mindset taught by modern education. It’s a mindset that explicitly rejects or problematises history. As a result, it has no clue that the new developments in the culture (Integral Consciousness) were built on the foundation of the old. That’s what our modern elites believe. They were educated to think that everything old is wrong. Accordingly, the “new” ideas they come up with are completely untethered to history, to culture, to common sense and to practical reality. Because those ideas don’t make any sense, the public doesn’t understand them. So, they are fed through the propaganda machine which turns them into the form we see in the public discourse; an endless stream of hysterical fear and dread whose sole purpose is to discombobulate the public into bewildered acquiescence.

In the face of the constant exposure to absurd ideas and feverish propaganda, the public is naturally tempted to fall back onto the safe old ideas which, even though they got us into this mess in the first place, are at least understandable. Thus, modern society swings back and forth between demented neophilia and reactionary populism. This is a system without a future. It’s falling apart before our very eyes.

So, even though Gebser talked in abstract terms of “consciousness” and “spirituality”, the Integral Consciousness has a very practical element and tying modern developments back to history is a crucial part of the picture. Only by understanding that past can we track where we might be headed. Gebser’s message was the same as Jung’s. Either we educate ourselves properly and face the future standing up, or we get dragged through the mud kicking and screaming. Currently, the west is choosing the latter option but it doesn’t need to be so.