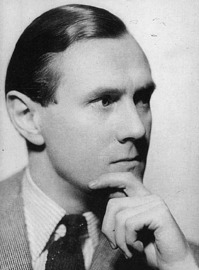

I’ve mentioned Rene Guenon a number of times in the past after being put onto him by a commenter on one of my Age of the Orphan posts (thanks again to Austin). Since then, I’ve read a number of Guenon’s works. I consider him to be one of the most eloquent critics of modern western society whose analysis has only become more valid since he died in 1951. However, in this post I’m going to discuss the main problem I have with Guenon which ties in with Jung’s analysis in Answer to Job and the theme of this series in general.

Guenon is an astute critic of the modern West and he wrote several books that express his criticism in great detail. One of the best of these is Reign of Quantity. Guenon introduces the book by noting that what’s going on in the modern world is all part of a grand cycle known in Hindu cosmology as the Kali Yuga. The name of a cycle is a Manvantara, which could be translated into English as “aeon” or “age”. In that way, the analysis is somewhat similar to what Jung was doing in Aion, although the timeframes in the Hindu tradition are seriously long. The Kali Yuga started in 3102 BCE and will last all the way til 428,899 CE.

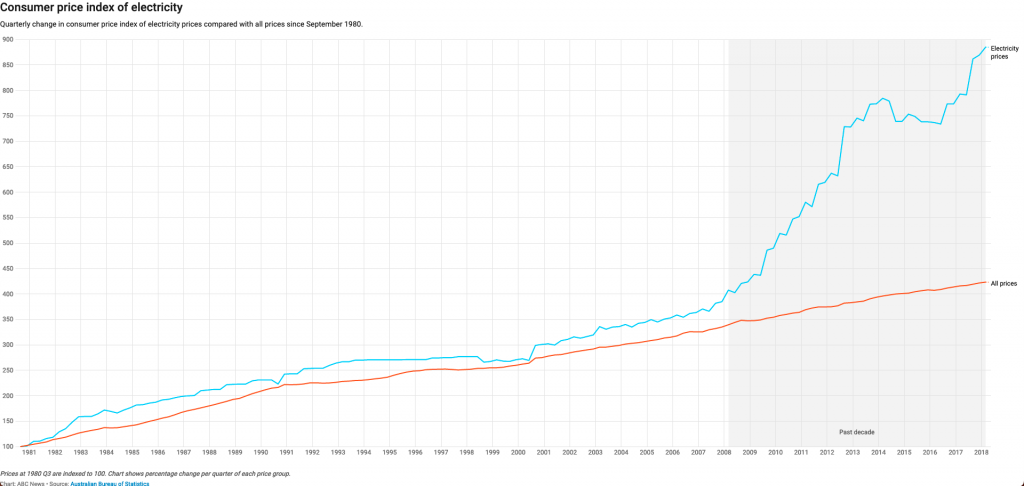

As I’ve said, I am in furious agreement with most of the details of Guenon’s critique of the modern West one of which is that we focus almost exclusively on the material world that can be quantified. It is clear we are obsessed with matter as evidenced by the fact that right now in a huge bunker in Switzerland scientists are smashing matter together in a giant particle collider (yes, that’s stretching the definition of “matter”, but still). I don’t have a problem with the content of Guenon’s analysis. I do have a problem with the idea that this is all foretold in some great cycle of history. The problem revolves around the age old questions of fate, free will and consciousness.

Let’s accept that it’s true that some great sage in ancient India, while meditating under a tree, stole the password and hacked into the central computer at Cosmic Headquarters and mentally downloaded the plans of the cosmos for the next trillion years. According to those plans, everything that is happening right now has already been foretold and the decadence of the modern West is just part of the cycle. If that is true, what can be the point in criticising the modern West for its decadence? If the modern West is just part of the inevitable cycle, a simple act of fate, surely there is no point in arguing about it. Yet, that’s what Guenon does. In fact, he spends several books outlining with wonderful clarity a principled critique of the West based on what he calls the traditionalist approach. But, again, what is the point of this traditionalist approach given everything is inevitable anyway?

Let’s put this in the form of a thought experiment.

Let’s say everybody in the modern West reads Reign of Quantity and completely agrees with Guenon that the traditionalist approach is best. Realising the error of our ways, we stop doing everything we are doing and re-arrange society according to Guenon’s principles. If we were to do that, we would have circumvented the Kali Yuga. The West would no longer be decadent materialists obsessed with quantity. The cycle would have been short circuited because we followed Guenon’s advice.

Alternatively, we could take a more Dostoevskyan perspective. We read Guenon and understand that everything is fate. It doesn’t matter what we do, the Kali Yuga will manifest anyway, society will spiral downwards in decadence until the new cycle starts its inevitable progression. One of the ways we might respond to this knowledge is to say “screw you, cosmos! We’re not playing your stupid cycle game” and proceed to commit mass suicide. In doing so, we would also circumvent the Kali Yuga because it is a cycle of humanity and if there’s no humans around you can’t have any more cycles of humanity. In both of these cases, the overarching pattern would have been broken.

It seems to me that Guenon can’t have it both ways. Either the cycle is inevitable or the act of analysing the problems of modern society can make a difference. (There is an obvious compromise position where fate determines most things while human will has the ability to initiate change but Guenon seems quite specifically to reject this).

The issue here, and this is where Jung becomes relevant, relates to consciousness. By reading Guenon, we become conscious of problems we were previously unaware of. Either we can use this consciousness to change direction or we can’t. If we can’t, then the consciousness is useless. Worse than useless, in fact, because we know what is going to happen but can’t do anything about it. We might prefer to be ignorant in that case. As the saying goes: Those who don’t learn from history are doomed to repeat it. Those who do learn from history are doomed to watch while others repeat it. Well, are those who read Guenon doomed to watch while the inevitable cycle unfolds or can they do something about it? Does the act of changing even one person’s mind make a difference?

Hold that last question in your mind. And let’s turn to Jung’s analysis in Answer to Job which deals with that very issue.

The Book of Job is undoubtedly one of greatest stories extant. Its universality can be seen in the fact that one of the core issues it deals with couldn’t be more relevant to modern times. The main body of the story is an extended argument between Job and four interlocutors. Job has been ruined by God despite living a life he believes to have been without blemish. He points to examples of his virtuous actions all in perfect accordance with the rules. None of his interlocutors contradicts him on this front. They don’t cite examples of him doing wrong or question his integrity. Rather, their arguments can be summarised as follows: God is omniscient and omnipotent and you are not. Therefore, you cannot be in the right.

We could translate the Book of Job into modern terms by imagining an elderly beggar on the street who is clearly suffering physical illness. The beggar tells the story of how he got into such a state and asks whether it is just. Four others, including a well-dressed young man name named, Elihu, approach. The young man, Elihu, clearly thinks very highly of himself. “One in perfect knowledge is before you,” he tells the beggar. He then proceeds to explain to the beggar why all this is for the best and the beggar must have done something wrong to deserve God’s wrath. And, even if he didn’t, God is all powerful and may do as he pleases.

This is the might is right argument and it forms the backbone of the Book of Job. For Job’s interlocutors, “justice” is the same thing as power. Because God is all powerful, he must be all just. As Job points out, the others have no skin in the game. They stand there well dressed and well fed. It is Job who suffers and nobody has even attempted to explain what rules he has broken to deserve such a punishment. The others are arguing rationally and intellectually. Job is talking from experience.

With very little modification we could translate the dialogue in the Book of Job into what we have seen ever since the corona vaccines have been rolled out. Countless people took the vaccine and then got sick. From their point of view, the vaccine was the cause. They did the right thing and now suffer. But nobody seems to care. On the contrary, television media personalities and groups of people on social media pop up to say that the vaccine could not have been the cause because it’s safe and effective. “Shut up and believe in God,” says Elihu. “Shut up and trust the experts,” say the modern mob.

If this was all there was to the Book of Job, it would still have perfectly captured a universal of human psychology. But, the stakes are raised substantially by the fact that we, the reader, know that the whole thing is a set up. Satan has convinced God to allow Job to be tested in a way that causes Job immense suffering. There’s much that can and has been said about that, but we’ll focus on the argument made by Jung in Answer to Job, which is as follows.

The treatment of Job was unnecessary because God is omniscient.

Now, omniscience is one of those concepts that seems simple and yet when you think about it quickly becomes problematic. What sort of knowledge is it that God has? Does his omniscience include all kinds of knowledge or just a subset? Does God know everything that happens for all of time or did God just create the rules of the universe and then press the Play button?

To short circuit a long philosophical diversion, let’s assume omniscience means something like Laplace’s Demon. That is, because God created the universe, he knows the starting variables of everything and because God has an infinite amount of calculating power, he could deduce intellectually any path of events. If he wanted to know whether Job was faithful, he need only calculate the sequence of events in his mind to get the answer in the same way a computer simulation works (only this computer is perfect).

But God does not do that in the Book of Job. What God does, prompted by Satan, is to carry out what we could call in modern language an empirical investigation; a test. Because it’s an empirical test, Job is directly affected by it. God allows Satan to first destroy all of Job’s possessions and, when that doesn’t work to break his faith, to inflict physical suffering. God says to Satan, have fun, just don’t kill him. It is the immorality of this that forms the core of the story, although presumably we draw a different moral lesson in the modern world to the one that would have been drawn at the time. In modern scientific studies, researchers are not allowed to inflict suffering on their subjects without prior consent so modern ethics recognises this problem (although, the history of science is littered with stories like Job’s).

Why would God put Job through such torture unnecessarily? Why do an empirical test instead of use his omniscience? That is the question we, the reader, must deal with and we cannot help but take Job’s side. This seems like an open and shut case where God is in the wrong. That is Job’s argument in the story. The arguments of his opponents cannot convince us because we know the bigger picture.

To skip over Jung’s argumentation and go to his conclusion, he believed the story of Job was so important because, even though Job ultimately yielded to God (and was rewarded for doing so), it was pretty clear he was not converted to the idea that might is right. There was now one man in the world who believed God had done wrong and because God can see into men’s hearts, God himself learned this. Therefore, God learned something about himself. It follows that God also has an unconscious mind (Satan can be seen to stand symbolically for God’s unconscious in the story). It is Job’s unwillingness to yield to an obvious injustice that allows God to see all this. Job, a mere mortal, not omniscient or omnipotent, has taught an omniscient and omnipotent God something.

In the story of Job, we have a God who is not an aloof mathematician. He is not a God of pure intellect who set up the rules, started the machine running and then went off to play computer games or otherwise amuse himself while the universe bubbled along. This God is actively involved. He cares (although as Jung points out, he cares mostly about himself). We know that he cares because at the start of the story he goes out of his way to tell Satan what a virtuous man Job is. He then personally meets Job at the end of the story to extract a pledge from him. It is because God cares and gets personally involved that he can learn. Now we have a God that can change. But that learning and that change comes from the “ground up”. The material world that God could wipe out with flick of his finger turns out to be worth something after all.

The story of Job implies a view that is in contradiction to Guenon’s. Guenon’s universe is one of timeless non-duality. Time and space are illusory. There is no change. It is all very similar to Plato. The material world is mere appearance. This is partly why the Christian theology is so radical because God himself manifested in the material world. But that amounts to God manifesting in illusion. Why would a god willingly do that? In the Jungian argument, it’s because God, following the Job incident, wanted to learn more about himself and he realised he could do so by becoming a man. Suddenly, matter and the material world are redeemed.

What if the idea that the material world is just an “illusion” is actually nothing more than an intellectual value judgement made a priori; the same kind of value judgement made by Job’s interlocutors or by people who say the vaccine is safe and effective. Psychologically, that value judgement relegates material existence to the unconscious. It is not valuable, therefore we don’t pay attention to it. But in the Jungian paradigm, one does not simply relegate things to the unconscious. Out of sight is not out of mind because the unconscious is also part of the mind.

Philosophers have a habit of doing this kind of thing. In Guenon, I hear much the same tone you can hear in Plato. Notice how in the Socratic dialogues, Socrates is never surprised. He never asks a question of his interlocutors except to lead them into a dialectical trap of his own making. He never learns anything. He never says “that’s a good point, Thrasymachus. I hadn’t thought of that before. Let me go away and think about it.” For Guenon and Plato, there is nothing to learn. They have ruled out the value of such learning (from the material world) from the start. The universe is a one-way street starting in the realm of timeless non-duality and flowing down into material reality but never back up again. Jung’s reading of the Book of Job and the Bible in general suggests that the Christian God came to a different conclusion and wanted to redeem the material world. In the person of Job, the material world rose up out of God’s unconscious and forced an individuation process to occur.

What’s all this got to do with the eternal feminine?

Well, firstly, it’s the thesis of this series of posts that we are seeing a similar individuation process occur right now and that process could be as significant as the process that led (in Jung’s belief) to the God of the Book of Job manifesting as a human in Christ; in other words, an epochal change. That would mean that something critical that has been relegated to the unconscious is trying to come to consciousness. That something seems to be related to the eternal feminine. But the eternal feminine is a nebulous concept and could mean many things.

One of them could be a concept mentioned in the last post: Sophia (wisdom). The word philosopher means lover of wisdom; philo + Sophia. To the extent that Sophia is the eternal feminine, it follows that wisdom could be relevant and I think that’s true. That why I believe Guenon’s wisdom is relevant. He is right, western society is completely lacking in wisdom right now. We need wisdom like a man who has just spent two days walking in the desert needs a glass of water. That’s why I agree with most of what Guenon says even though I disagree with his underlying philosophy. There may very well be a sphere of timeless non duality. But in relation to it, I’m inclined to use Wittgenstein’s catchy phrase and say “whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must remain silent”. Down here in time and space, the dualities still seem to hold even though the point is to resolve them into a trinity (or perhaps even a quarternity as in the Fourth Face of God).

However, I’m increasingly skeptical that wisdom is all we need partly because wisdom is necessarily about the past. It’s wisdom that said “might is right” when that was considered the truth. It’s also the case that the magnitude of what looks to be taking shape is enormous in which case it will be a long time before wisdom can re-establish itself.

So, maybe the eternal feminine that we really need would be the one that Dostoevsky wrote so much about and is best embodied by the Virgin Mary. That eternal feminine would indicate that what we need now is faith, forgiveness and, most of all, love.

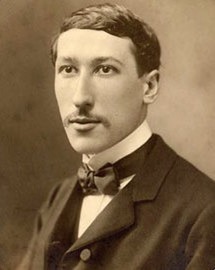

On this score, the poets, writers and artists may be our better guide (an idea that Plato would have abhorred). Dostoevsky is one and so too, I believe, is Patrick White. We’ll explore that more in a future post.

All posts in this series:

Patrick White’s “Voss”

The Eternal Feminine, The Devouring Mother and the Fourth Face of God: Part 1

The Eternal Feminine, The Devouring Mother and the Fourth Face of God: Part 2

The Eternal Feminine, The Devouring Mother and the Fourth Face of God: Part 3

The Eternal Feminine, The Devouring Mother and the Fourth Face of God: Part 4

The Eternal Feminine, The Devouring Mother and the Fourth Face of God: Final