One of the questions I’ve been puzzling through recently is the state of rites of passage in modern Western society. Nominally speaking, we seem to have very few rites of passage and this also seems to be tied in with the absence of the Elder archetype in our culture since, from an anthropological point of view, it is the Elder who conducts rites of passage. No rites of passage, no Elders. Makes sense. But is it actually true?

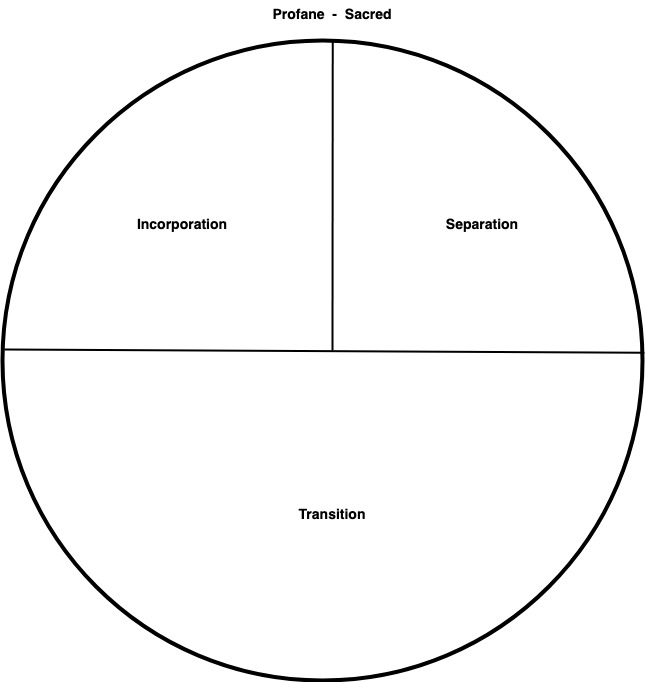

Let’s begin our answer to that question by defining some terminology. The rites of passage concept was coined by the anthropologist, Arnold van Gennep, based on a comparative study of ceremonies and customs from across many different cultures. What van Gennep realised was that, beneath the surface differences, rites of passage all had the same form which he characterised as a three-part movement out of the status of “profane”, into the status of “sacred” and then back to “profane”. We can diagram this using a circle since a rite of passage begins where it ends i.e. in the status of “profane”.

There are three phases to a rite of passage: Separation – Transition – Incorporation. In the first phase, we separate from the normal world that we live in day-to-day. We then enter a new state that is different from that world. That’s the Transition phase. The Incorporation phase involves navigating back to the everyday world with some new thing or property that we have incorporated or made part of ourselves.

In addition to van Gennep’s original concept, I would add a few points. Firstly, a rite of passage is a linkage between the individual and society. We can think of it as a way for society to initiate individuals into a culture. Since most rites of passage are designed to navigate through a dangerous period of time, it is also a way to lend assistance to the individual. For example, almost every society has elaborate rites of passage around pregnancy and pregnancy has, for most of history, been very dangerous for both woman and child. Thus, we can also think of the rites of passage a way to assist the initiate through a dangerous period.

Another point about the rites of passage is the one mentioned above: they are almost always conducted or led by a societal Elder. Rites of passage are about navigating through a period of sacredness. While the individual is in sacred status, they are usually not considered a full member of society. They are in a kind of limbo. It is the Elder who guides the initiate out of limbo and back to being a full member of society.

The Elder who conducts the rite of passage is always a representative of an institution of society. Traditionally speaking, there are three classes of Elders: the political Elders, the religious Elders and the warrior Elders. Here is another key point. The Elders themselves are “sacred” since they have more power than the other members of society. Accordingly, there are usually elaborate rites dealing with the interaction between Elders and general members of society. These are there for the “protection” of both parties since Elders are a threat due to their power and their power puts them at risk from the rest of the public. It’s also for this reason that Elders are located in a “sacred” placed that is separate from the general run of society.

From this lightning overview alone we can see why rites of passage are foreign to us in the modern West since with our extreme secular and materialist outlook this all sounds like a lot of mumbo jumbo. Nevertheless, we do have our rites of passage and our Elders. Let’s take one example: a job interview.

For a job interview, there is already an implied change of status for you as the interviewee. That status can be called “available to work”. Most of the time when we are employed, we are not looking for work. That is the normal state of affairs. When we start looking for work, we have changed state. This signals the beginning of the Separation phase. We want to separate from our current job and take a new one.

Rites of passage almost always mark the Separation from the everyday with special clothing. This is true of a job interview since most people will show up in a suit or similar formal outfit. Assuming you actually want the job, you’ll probably make sure you get a good night’s sleep the night before so that you perform at your best in the interview. Before the interview itself, you might take a shower and pay extra attention to your grooming and appearance so that you look your best. These are all parts of the Separation phase; the break from normal life.

The transition phase begins with the interview and is probably marked by you shaking hands with the interviewer(s). The interviewer in this case is the archetypal Elder. They represent an institution of society (the organisation offering the job) and they have a position of power within that institution. They will also be dressed appropriately for the occasion. They will use formal, polite language and, in general, there is a special code of behaviour and a fairly fixed format for a job interview that is different from everyday life. All this belongs to the Transition phase of the rite of passage.

When the interview ends, you move into the Incorporation phase. What is up for grabs is quite literally whether you will be incorporated into the company. If the Elders of the company agree to incorporate you, your status changes from “available for work” to not available and there are a variety of culturally prescribed ramifications including tax payments, banking arrangements and your formal incorporation into the company via whatever onboarding and training they need to give you.

In short, a job interview is a paradigm example of a rite of passage from an anthropological point of view.

Since a job interview is a rite of passage, the question then arises: why don’t we think of it in those terms? My guess is this: we are unconscious of the rites of passage in our own culture. An anthropologist traipsing through the jungle with some strange tribe is acutely aware of the rites of passage of that tribe because they are foreign to him or her. Once you’ve viewed or studied enough different cultures, you can learn to see the formal, outward markers of a rite of passage. But from within a culture, you don’t see a rite of passage as such because it’s just a part of the culture. We experience our own culture subjectively, not objectively.

But there’s a more philosophical reason why we don’t recognise our own rites of passage and this relates to van Gennep’s concept of religion which he defined as metaphysics + magic. Magic can be further defined as a ceremony which achieves a specific effect in line with the metaphysical assumptions of the culture.

While the effect of the magic “works” on us, we don’t think about it any further. It was Nietzsche who made the point that the metaphysics of a culture are only ever brought into question when they no longer work. It’s only once the magic stops that we are inclined to start doubting. It follows that the arrival of philosophy implies a religious crisis. Consider that the first pages of Descrates’ great work Meditations on First Philosophy involve him doubting the assumptions of his culture.

We seem to be in the middle of exactly such a religious crisis in modern Western society and this implies that our metaphysics, the religious basis of society which grounds our rites of passage, is starting to fail to produce the magic. We have already identified one element of that metaphysics. A job interview is a rite of passage the magic of which is to create an employee who will contribute to the economic prosperity of a company. The economic prosperity of companies is the basis for the economy of our society. The underlying assumption, the metaphysics, is capitalism. In order to understand the other main pillars of our metaphysics we first need to zoom out and do a quick historical overview.

As we have already noted, the Elders of most societies throughout history can be grouped by three archetypes: the Ruler, the Sage (priest) and the Warrior. Plato’s Republic is very largely concerned with maintaining the right balance between these groups. In practice, the three are often combined in different ways. When Octavian became the supreme ruler of Rome, one of the noteworthy things that happened was that he took all three positions for himself. He was commander-in-chief, tribune, censor and pontifex maximus (Pope). He was the Ruler, the Warrior and the Sage.

All through the Roman empire, including the later Eastern Empire, the Caesar retained authority over the church. That is a fairly common state of affairs for most societies throughout history but in western and northern Europe, following the collapse of the western Roman Empire, something strange happened. There were all kinds of small kingdoms and warring political factions but the church managed to unite all these under the rubric of Christianity leading back to the Pope in Rome. The result was that, for many centuries, the Church enjoyed supremacy over the political leaders.

One of the main reasons this could happen was because of the way in which Christianity got integrated into the Roman Empire in its later phase. In Roman society in general, there was never a separation of church and state. What we would call administrators also had a religious function. This was also true of the highest political offices. When Christianity became the state religion, what we call bishops retained the old administrative functions and implemented the new religion alongside them. The word bishop comes from the Latin episcopus which simply means “watcher” or “overseer”. It was a title given to government officials.

In the aftermath of the Roman Empire in western and northern Europe, something of the administrative and organisational structure of the church remained in place including the bishops and their boss, the Pope. At that time, the glory of Rome was not forgotten by the barbarian tribes of Europe and they were eager to align themselves with it. That seems to be the marketing angle that the bishops and other churchmen used to win over the various warlords and create a unified region under Christianity. For a brief period, the Pope really was the boss.

Over time, the political leaders of the region came to resent the power of the Pope and some even went to war against him. Eventually, a kind of equilibrium was reached in which the church, following the pattern inherited from Rome, retained a significant share of the administrative functions including control of education, scholarship, the sciences and bureaucratic record keeping.

Enter Martin Luther (stage right).

We said above that a philosophical challenge to the metaphysics of a society implies a religious crisis. That is what the arrival of Luther represented. Luther was a gifted scholar and intellectual who wrote extensively. Much of what he wrote is very hard for us to understand these days but one thing rings through very clearly even to modern ears. Luther denied the authority of the bishops and the Pope. For him, they had strayed far too much into worldly affairs and forgotten the religious basis of their role. Forget the fact that the church had always been involved in worldly affairs ever since its beginning in ancient Rome. Forget the fact that it was solely because of the church that anything resembling civilisation even existed in northern Europe. Luther wanted them gone.

The religious crisis that Luther led eventually led to the metaphysical basis for our modern society, although mostly in ways that Luther would have despised.

Firstly, the reason Luther had support from the kings and princes of Europe was because they saw the opportunity to reduce the power of the church. It took all the way til the 19th and 20th centuries, but eventually the state finally pried the last administrative and cultural functions of education and record keeping out of the hands of the bishops and popes. We swapped bishops for bureaucrats. Since bureaucrats are not Elders, there was a vacuum. That vacuum was filled by another group: the Technocrats.

Consider the two most important rites of passage in any society: birth and death. Once upon a time, these were presided over by priests as our religious Elders. Not any more. Where are we born and where do we die? In hospital. Who presides over our birth and death: doctors.

Doctors have become the Elders who navigate us through the rites of birth and death. Ergo, doctors and technocrats more generally, have become our religious Elders. Once upon a time, a baptism was the rite of passage by which we joined society and the baptism certificate was the official proof of our existence. Now, a doctor fills out a birth certificate and a death certificate. Same rites of passage, different Elder and, more importantly, different metaphysics.

Luther and the other protestants were responsible for this development for at least two reasons. Firstly, they demanded to get rid of the religious Elders of bishops and priests. For them, we didn’t need an earthly Elder since we had Jesus as our spiritual Elder and we could answer to him directly. Nice idea. Doesn’t seem to work in practice.

The second, and related, problem is that Protestantism created modern atheism by diving the public up into those who were saved and everybody else. As John Calvin put it: “there remaineth nothing else for the rest but the reproach of atheism”. It took several centuries, but eventually Calvin was proven right and most people eventually accepted that they really were atheists, as can be seen in the collapse in church attendance. Modern secular materialism is the logical outcome of Protestantism. The protestants wanted to get rid of the priesthood. Instead, they created a vacuum which was filled by the new priesthood: the Technocrats.

There is one more group of Elders that Protestantism gave birth to and, again, we are going to skip over the details and simply cite the book which summed it up: The Protestant Work Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Since we have already provided the analysis of how the rite of passage of the job interview fits the metaphysics of capitalism, we simply point out that the societal Elders who rule over this sphere are not just the capitalists anymore but also the Technocrats in the form of the bankers and other financial wizards.

There remains just the political sphere to talk about and let’s again skip the detailed analysis by simply pointing out that a democratic election is a paradigm example of a rite of passage. Here in Australia, the Separation phase involves the Governor General dissolving parliament. The Transition phase is the election campaign itself and the Incorporation phase is the swearing in of the new parliament all done with a ceremony and pomp befitting an old-fashioned rite of passage.

How does parliamentary democracy relate to the Reformation? Well, the protestants wanted to run their churches in a completely democratic fashion with elders and other officials elected by popular vote of the congregation. This mostly never happened because the princes and kings of Europe did not want to encourage democratic tendencies among their subjects. It took a few hundred years and a few decapitated kings for the protestants to win the argument.

From this historical overview, we can see the metaphysical foundations of the modern West ushered in by the religious crisis of the Reformation are democracy, capitalism and science. Each of these has its own societal Elders. Each of these has its magic (ceremony + effect) which is manifested in the rites of passage of our culture.

I mentioned at the top that these metaphysical assumptions are now being called into question. We can see that that’s true from the election of Trump. Trump is a capitalist who became President thereby fulfilling two of the primary Elder roles of the modern West. In the aftermath of his election, we saw a flurry of learned think pieces, including from some famous names from academia, honestly stating that democracy was broken and had to be replaced by, well, something else (exactly what wasn’t clear).

The one thing many westerners seem to agree on is that democracy isn’t working and after the last few years of inflation, capitalism isn’t looking too crash hot either. That leaves the third metaphysical foundation of modern society: science. As we saw during corona, science has become corrupted too. That message has been reinforced in just the last couple of weeks with the growing scandal around plagiarism in academia. What lies beneath that scandal is the fact that most of modern academia is a fraud that is riding on the coattails of the faith (and it really is faith) that the general public has in science.

Those are the broad terms of the religious crisis that has been building now for several decades in the West. What makes our crises different from the Reformation is that the Reformation was led by the heroic figure of Luther. By contrast, nobody is leading our crisis. Rather, our crisis presents itself as a force of nature like green slime bubbling up from the sewer. In next week’s post, we’ll try and identify where the slime is coming from.

What lies beneath the plagiarism scandal is an attempt to silence protests against Israel’s genocide of Palestinians. It’s similar with the “democracy isn’t working” idea, and honest science – powerful people aren’t getting the answers they want.

Sofie – yes, because academia and “science” have long since become little more than ways for monied interests to buy propaganda they can use to further their own agenda rather than the seeking of truth.

From this line of thought then it is interesting to compare western countries that are Protestant to those that are Catholic. This neatly fits basically northern and Southern Europe and their colonial descendants, which probably has some deeper meaning relating to climate (Irish exception).

The Northern European and descendent colonies seem to be suffering the religious crisis to a much greater extent, and from personal experience it seems the Catholic countries have held onto their rites of passage, even in terms of carnival and religious holidays that were such a big part of life in the Catholic Middle Ages.

There is always the Protestant criticism that these countries are ‘lazy’ (again climate probably comes into it, the English regarded Melbourne as the optimal Australian climate because people would stay indoors and work more) but that’s the point, there is more to life than work.

Skip – it’s noteworthy that the north (especially England) got rid of the guild system earlier. Although Luther can’t take all the blame for that, the reality is that his war on the church increased the power of the state and the proto-capitalists and this helped with the undermining of the guilds most of whom had reciprocal relationships with the local church. Since the guilds operated to restrict supply in order to manage the prices, they would probably be considered “lazy” by modern standards. It’s also true that, from a rite of passage point of view, the guilds were an old-school rite of passage lasting many years; actually, very similar to religious cults in a formal sense. The modern “job” is a pale shadow of a rite of passage by contrast.

Simon,

A thought – The hero’s journey is an initiation, and we live in a society where everyone is the hero of his or her own story. But, how do you tell the heroic story in a society with less and less initiations?

Bakbook – the Hero’s Journey has the same underlying 3-act structure as the rites of passage –

So, one way to think about it is that the rite of passage is the external, social facing process and the hero’s journey is the internal. They have the same structure because one is the macrocosm (society) and the other microcosm (individual). What happens when the rite of passage has no corresponding hero’s journey? You get empty ceremonies which are done because people are following the old ways without knowing why. What happens when you get hero’s journeys with no corresponding rite of passage? Loneliness, isolation and solipsism.

Of course, there’s another way which is that instead of trading rites of passage we trade actual stories and that is what we do in modern society. We make up for the absence of rites of passage by telling stories (where stories also includes theories, philosophies etc).

This is also how politics is conducted. The Roman governing class enforced its authority by forcing citizens to performs rite of passage (eg. the cult of Caesar). Our ruling class enforces its authority by imposing stories on us (propaganda).

Hey, Simon, happy new year! Hope you had a good break. Was reading CJ Hopkins on psychosis, individual & societal, so maybe that coloured my reading of this post, but I read it w/ the idea of psychosis as an opportunity for initiation, & instead what we get in this society is systemic suppression of altered states in general, whether drug-induced or just the misfiring of brain chemistry, & all because such states can be dangerous. The system wants to keep us safe. When what’s actually most endangered is the stability, hence the ongoing existence, of the system. Luther would presumably be deemed psychotic today &, if not restrained, pressured to take deadening medication. Some theorists have posited that Christ, too, was insane.

I’ve been seeing the same GP for a quarter of a century – if less & less often lately for obvious reasons – & while no doubt both of us have changed, it seems to me that in recent years, my GP has been sounding increasingly crazy. I wonder if this has to do w/ the stresses of being a quite logical person working (though they’ve reduced their hours) in an increasingly irrational system? Our last disagreement centred on my refusing a medication because I could find no research to convince me it was safe, let alone effective. The argument quickly grew circular because they asked what I needed to know to be convinced to take it. I tried to point out that the goal wasn’t for me to take medication, but to deal w/ my condition in the most beneficial way. But the thing is, my GP wasn’t used to having their judgement questioned & became uncharacteristically inarticulate.

It seems that when authority isn’t questioned, the authorities forget how to think about the theories & practices on which their authority rests.

Shane – happy new year to you too!

I think I’ve mentioned before how the protestant doctrines caused real distress among those who took them seriously, which was most people at that time. I mean, the protestants were basically saying that most people were going to hell and there wasn’t anything you could do about it. They did that at the same time that they deprecated the role of the priest in the lives of believers which meant there wasn’t anywhere to turn for solace. Max Weber’s theory was that that was a big part of the reason why many people found solace in work and thereby accidentally created the conditions for capitalism to thrive.

That’s an interesting story about your doctor. I’m guessing most doctors are overworked and are trying to take the path of least resistance. Since most people want to be medicated, they get used to just prescribing something and maybe they forget what the real point of their job is. It’s quite a common problem, not just among doctors. I see it all the time in my field. My go-to question in such situations is “what problem are we trying to solve?” That usually forces a reset of the debate. I guess in the doctor-patient relationship the doctor might like having the “power” and might not like being questioned.

Simon. The banks are the Church of the Dollar, right down to the architecture. The doctors and scientists of the new priests of science, right down to the white coats. The politicians are still the politicians. But who are the warriors?

Jinasiri – the mercantilists and capitalists are the warriors. European dominance has always been predicated on trade and, although there was a role of the military, it was mostly used as a last resort. If we compare the Roman Empire against the British-American Empire, we see that the Roman was based on military dominance. The Warriors really were warriors and they were the cornerstone of imperial power. The British-American Empire has been predicated on trade, hence the capitalists have played the role of the Warrior. Note that this is even true for the metaphors used in business which focus on competition and war.

Simon. Crickey! That’s seriously insightful. Explains the Aussie private boys school obsession with rugby.

You have to remember that many of the early mercantilists were little more than pirates whose “business plans” were predicated on stealing gold from the Spanish (who were stealing it from the South Americans) and then picking up some things to sell on the way back 🙂

Who were these pirate mercantilists? The English? And when?

Read up on Francis Drake. He is the best exemplar in the 16th century. And, yes, the English had more than their share of pirates 🙂