It is one of the strange paradoxes of our time, and might be unprecedented in history, that the USA is running an empire even though a large share of the public in that country, and in most other countries, believe that it is not. In the aftermath of the WW2, Britain and other European nations all dismantled the remaining formal, Exoteric structures of their own empires and we were told we now lived in a post-colonial and, hence, post-imperial world.

Now, we might say that the reason everybody is pretending the US is not an empire is because the empire works better that way or that it’s not polite to admit it. Even if that were true, it would be very weird by historical standards. All past empires have had no problem letting everybody know that they were the boss. In fact, they went out of their way to do so because empire was largely based on the projection of power and it was in the interests of the emperor to seem as strong and domineering as possible. Even the British were happy to proclaim that they had an empire. Rule Britannia! and all that.

I’m going to argue that the denial of American imperialism runs much deeper and involves an inherent psychological dimension which is a big part of the reason for the psychological dimension of US dominance. Americans are not just pretending they aren’t running an empire for pragmatic reasons. They’re doing it for psychological reasons, ones that have been embedded in the culture from the beginning.

What that psychology amounts to is a rejection of the Father archetype. That development is not unique to America. In fact, it began in Europe with the Reformation. But America was born out of a group of people who were fleeing from the Tyrannical Fathers of Europe and so it received an extra strong dose of the psychology.

Of course, what is going on is not only psychological. The rejection of the Father was a rejection of a specific form of power; the masculine form of power which has been what we traditionally associate with imperialism. By rejecting the Father, the Americans were rejecting imperialism. That’s what they thought and that’s what they still think. But in the political aspects of that rejection lay the seeds of a new form of power which eventually gave rise to a new form of imperialism. It is that new form of power that has been relegated to the unconscious mind. More specifically, it was always unconscious, at least in the mind of the general public.

It’s going to take several posts to lay the analytical foundation by which the above analysis will make sense. The first assumption that we need to make clear is the unity of the microcosm and macrocosm. Now, the microcosm and macrocosm are concepts usually discussed in theology and philosophy to make the claim that the human individual is of the same structure, or type, or material, as God, the cosmos, the universe or similar holistic concepts. In this series of posts, we’re going to use the microcosm-macrocosm concept in a more limited fashion. The microcosm is still the human individual. The macrocosm is civilisation.

Civilisation is one of those concepts that we all take for granted and yet, when you start to question it, the definition begins to slip through your fingers. Let’s avoid that and break all the rules of philosophy to engage in a piece of circular reasoning. We have said that civilisation is the macrocosm to the microcosm of the human individual. It follows that, whatever civilisation is, it’s the same kind of thing as a human individual. Since we know what humans are, we can use ourselves as a template to define civilisation.

What led me to this idea in the first place was Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious which followed from the work he and Freud did around the personal unconscious. The personal unconscious consists of the things that have been pushed out of the conscious mind, usually as a result of some kind of trauma. What Freud and Jung realised was that the “energy” pushed into the unconscious had a habit of bubbling back up into consciousness in all kinds of weird ways and the psychoanalyst’s job was to try and untangle the mess and get to the root of the problem.

In some way, that’s exactly what we’ll be doing in this series of posts, only it won’t be a person laying on our psychologist’s couch but western civilisation in general, and America in particular.

Although Jung’s collective unconscious idea was born out of the work he did on the personal unconscious, he ended framing it quite differently, which is unfortunate since it’s the perfect term for the concept we need. So, let’s change the phrase slightly and call it the societal unconscious. The societal unconscious then becomes all the things which have been pushed out of the collective mind of a society and into the unconscious.

If this sounds a bit whacky, consider any group of people you have ever belonged to: a family, a sports team, a music group, a volunteer organisation, a small business, a corporation or a government department. Didn’t that group have a specific set of things that it consciously and collectively thought about? Didn’t that group also have a specific set of things that were not to be spoken about? Most of us have had the experience of raising something in a group and being gently, or not so gently, informed that the topic is verboten. That is the societal unconscious and we can contrast it with the societal conscious. Together, we get a collective mind that mirrors the individual in its structure.

Jung believed the contents of the collective unconscious to be universals of human psychology. But we can adapt his idea and, again, limit it to a particular civilisation. When we do so, we get very close to the work of the comparative historian, Oswald Spengler, who investigated the shared set of underlying ideas that seem to unify civilisations. Jung was concerned with the universal concepts of the collective unconscious. Spengler was concerned with the specific concepts that grounded specific cultures.

All of this is prima facie evidence for a correspondence between microcosm and macrocosm at the mental or psychological level. What about the physical or biological level? Each of us requires a quantum of energy in order to survive and go about our day. The same is true of civilisations. All the people who show up to work at a giant corporation each day need to get there somehow. There needs to be physical transport infrastructure and a source of energy to make that happen just as we all need a source of energy to do our daily work. Civilisations seem to have a metabolism just like other organisms; another correspondence between microcosm and macrocosm.

It was the comparative historians, Spengler and also Toynbee, who posited the microcosm-macrocosm idea we have been talking about and they did so by noticing another very important correspondence between the two. What they noticed was that the cycle of civilisation seemed to correspond to the human lifecycle. Spengler, in accordance with the materialist philosophy that had become dominant in the 19th century, used an explicit biological metaphor to describe civilisation and, in particular, to account for why civilisations die. They simply “run out of energy”, he said. They lose their vigour just as do elderly humans or other animals and plants.

Toynbee disagreed with Spengler on this point but then he needed to come up with his own reason why civilisations die. “Suicide” was his answer, which is a strange thing to say since suicide is a conscious and deliberate act and it seems clear that civilisations don’t deliberately kill themselves. A much better explanation would be to say that civilisations unconsciously kill themselves i.e. it is things which civilisations push down into the unconscious and, therefore, fail to deal with that end up doing them in.

This whole debate goes away if we invoke our definition of the microcosm and macrocosm. We have said that civilisation is the same kind of thing as a human being. We agree with Spengler that there is a biological component and we agree with Toynbee that there is a psychological and even a spiritual component. It’s not a question of either/or, it’s both.

What I came to realise as I was working through the concept for my upcoming book was that both Toynbee and Spengler had identified in the macrocosm of civilisation an identical idea to one that I had been using to describe the human lifecycle. I’m referring to the archetypes.

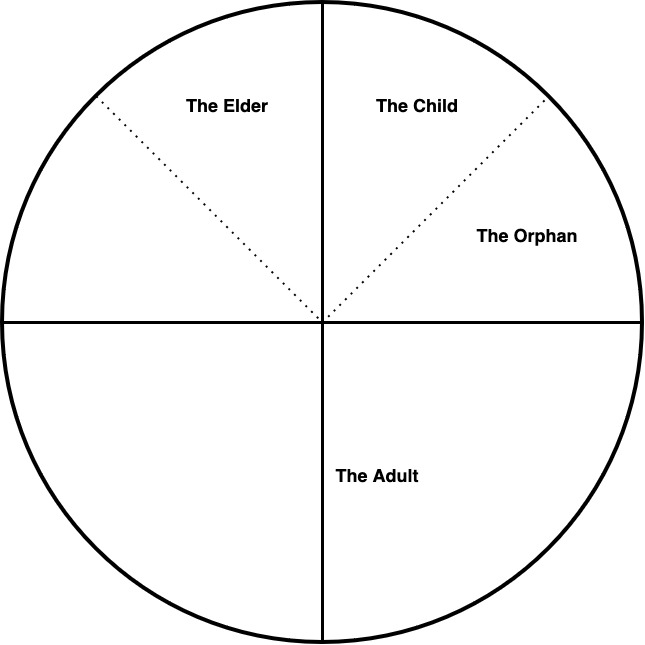

The archetypes are the segments of our lives. They are the common patterns that we each go through. Of relevance to the above discussion, the archetypes have both a biological and a psychological (and almost certainly also a spiritual) aspect. We can map the archetypes on to the human lifecycle as follows:-

There is a certain amount of subjectivity in how we divide up the lifecycle but the two archetypes everybody would agree on are Child and Adult and these are true universals of human culture. In my opinion, the Orphan and Elder are almost equally well-attested on both biological and anthropological grounds.

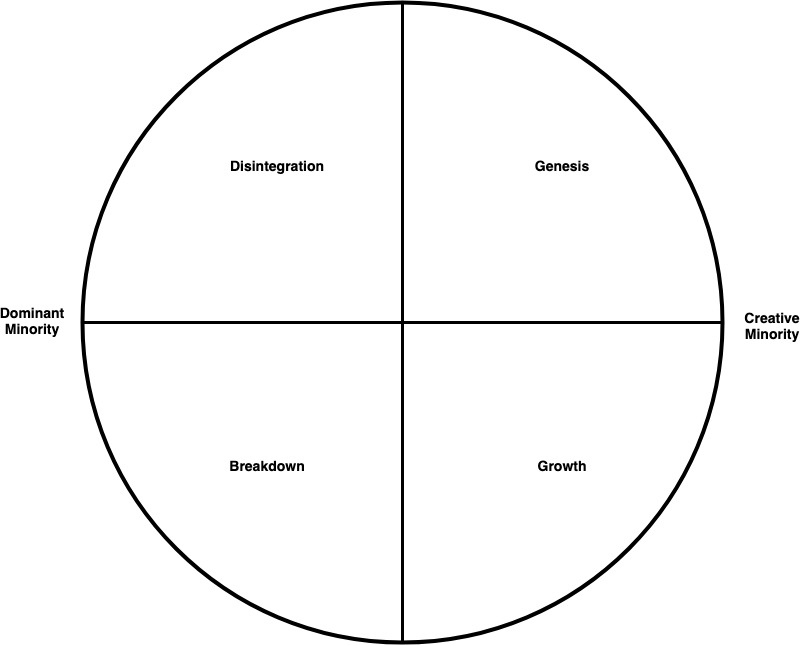

What is important is that both Spengler and Toynbee also divided up the cycle of civilisation into archetypes. Spengler posited a two-part distinction he called culture and civilisation. Toynbee posited four: Genesis, Growth, Breakdown and Disintegration. We can map these onto the cycle of civilisation in exactly the same way as we map the archetypes of the human lifecycle.

Here, then, is the hypothesis or thought experiment we will be following in this series of posts. If the microcosm and macrocosm really do share the same underlying structure, then we would expect the archetypes of the macrocosm to follow the same pattern as the archetypes of the microcosm. Just as each one of us goes through puberty, for example, and just as our experience of puberty has common factors that we all experience while also having personal ones that are unique to ourselves, so too do civilisations go through the same kinds of growing pains. The growing pains that occur during the Genesis phase of the cycle have shared properties that occur across all civilisations. That is the basis for all comparative history.

What our definition of the microcosm-macrocosm implies is that the archetypes really are the same. We can make that explicit by renaming Toynbee’s third and fourth archetypes using more neutral terms. When we do that, we get something like this:-

| Microcosm | Macrocosm |

| Child | Genesis |

| Orphan | Growth |

| Adult | Maturity |

| Elder | Old Age |

Although there are plenty of avenues to explore within this analytical framework, our focus in this series of posts is going to be the psychological. It cannot be a coincidence that western civilisation gave rise to the Freudian psychology. We have said that America was predicated on a rejection of the Father. But the more general point is that western civilisation has had daddy issues right from the get go. We’ll be talking about that more in the next post.

Hi Simon,

Spengler called it correctly. If a person was being cheeky, I could say that civilisation runs out of the mojo to fix the very problems it creates. 😉 And I like your point about how some issues are non-discussable, which is weird because it makes the failure more likely. There’s something really dark about having non-discussable wider issues in a civilisation. I do hope that you’ll explore that blindness further? I’m of the belief that we’re now at the point where issues are being tackled as if they were a narrative to be corrected, and that’s just odd.

Incidentally, the inverted bell shaped curve is hard wired into existence, in fact it is present in much wider contexts. Even the solar system life cycle follows that curve. It sounds a bit fatalistic.

Cheers

Chris

Chris – I have a story about a collective unconscious that you’ll appreciate. A small business owner who would never, and I mean never, allow any discussion of financial problems. I’m talking about somebody who would fly into a rage and scream and shout if somebody told them in the politest way possible that, for example, there was a cash flow problem. As a result, the entire subject became completely off-limits and was never discussed. It had been relegated to the unconscious.

This is a point that Freud and Jung made. Just because something is relegated to the unconscious doesn’t mean nothing happens and doesn’t even mean that it doesn’t “work”. In this case, the business still continued and, as far as I know, still does to this day. It’s just that that subject is never discussed.

It seems that most cultures have had a certain deeper wisdom regarding this phenomenon that is present in older religious ideas, but it really isn’t that obtuse or difficult if one merely ‘considers the Lillies’. Is there anything in the universe that doesn’t follow this cycle?

Something I find interesting about it is that in many cases (including human lifespans, but Spengler pointed out that this is particularly true of civilisations) the peak can happen quite early, perhaps in the first quarter, and that the old age/winter period can last a very long time.

Skip: depends what you mean by “peak”. It’s weird that all the things we associate with civilisation belong to the late stage of the cycle – law, order, wealth, power – while the early phase is the time of maximum creativity and novelty. Which is a pretty exact description of our lives too. Part of becoming an adult is giving up the possibilities of youth and choosing a life path. Same thing happens with civilisations. Of all the things the civilisation could have been, only one path gets chosen. But choosing one path also creates a concentration of energy which is the very definition of strength. Thus, peak strength comes later in the cycle.

Yeah I get you but I’m more talking about places like China where it was sort of frozen in stasis for a long time but never actually dying out. Same thing can happen with an old trees where it becomes huge and static but holds on in this state for a very long time.

If you live to 100 half your life is lived in what used to be considered old age. I guess I’m saying the growth and creative phase is such a short flash that then settles into long periods of maintenance.

True. Which is why Faustian civilisation is very unusual. If we really are in the Universal State period, which I think we are, then we should be settling down into the stability that all empires show. That’s what many thinkers of the 19th century believed had already happened. Whatever else you want to say about the modern world, the usual boredom of stability is not one thing we have achieved. Although, to what extent this is purely psychological is interesting. Maybe we really are in a stable period but it’s because our elites rule through psychological means rather than ceremonial ones as in Rome, for example, that it is subjectively different.

Hello, Simon

Joseph Henderson has the concept of the cultural unconscious. It seems to me that it matches yours. And also what Samuel L. Kimbles and Thomas Singer call “cultural complexes.” In addition to this, Jungian analyst Michael Adams also touched upon this term and redefined Henderson’s concept as another dimension of the collective unconscious.

I think you’re onto something there with the psychological aspect, as since WW2 and the big heated clash of contending states of Faustian Culture in that period intra state conflict between the members of the Faustian Culture has been non existent and in fact quite boring. Like late republic early empire Rome, the conflicts are no longer between the various representatives of the culture, but between Faustian Culture and other cultures and civilisations.

If you were just to focus on the Faustian heartland in Europe since WW2 it has been very stable and boring, with conflicts bubbling to the east but not really any threat if it weren’t for the adventurism of the Europeans themselves. Same with the North American continent. It’s perhaps just the global spread of the pseudomorphisis and constant propaganda barrage that it has made it seem more spicy than it actually is.

Michael – thanks a lot for those references. I’ll definitely check them out. I must say I’ve been surprised how well the microcosm-macrocosm assumption works in practice and the idea that cultures have an unconscious is kind of an obvious one hindsight!

Skip – yes, I don’t think it’s a coincidence that general social trend to the psychological coincides with the arrival of film. As an actor friend of mine once said “movies are dreams” and so we see a big cultural lurch into the unconscious and irrational at around that time. In an archetypal sense, I’d say the Orphan phase of the Faustian begins with the printing press and the mature phase with film.