Most techniques of propaganda also have a concomitant form as a cognitive bias or even a logical fallacy. There was an idea that was popular about a hundred years ago that, if all these biases were removed and only strictly logical information produced, then all propaganda, bias and fallacious reasoning would go away and we would live happily ever after in a reasonable and rational utopia. That’s not going to happen for a variety of reasons that are too long to go into here. The best we can do is simply be aware of our biases and the biases we are being invited to fall into when consuming propaganda.

One bias that is invoked all the time in propaganda is anchoring bias. Anchoring bias occurs when we allow an ‘anchor’ to skew our judgement on a particular matter. Often the anchor is the first piece of information we receive but it can be any other piece of information to which we give unjustified importance. As with other general cognitive biases, anchoring bias is not just seen in propaganda. It is a technique that is also used by skilled negotiators. Let me give an example from my experience so we can see how it works.

In China, as in most Asian countries, it is expected that you will haggle about the price of an item you are thinking about buying at a flea market. In fact, it is considered bad manners not to haggle. This is something we westerners have almost no experience in and so we tend to make very clumsy moves in such a negotiation. I never really got the hang of haggling. However, I was fortunate on one occasion to see an expert form of negotiation and also a classic example of overcoming anchoring bias.

I was on a work trip to China. An Indian colleague and I were walking around a flea market. He wanted to buy a trinket to take home to his wife and spotted a piece of jewelry that he thought she would like. We stopped at the stall and he asked the woman behind the table what the price was. She said it was 200 yuan. That was the anchor – the initial price from which all further negotiation will take place. If it was me, I would probably have counter-offered with 75 yuan. The stall holder would then probably say 150 yuan and we would end up somewhere in between. As a naïve westerner, I would get the experience of feeling like I had negotiated well and the stall holder would get probably ten times what the item was worth. Win-win.

But on this occasion the stall holder was negotiating with an Indian. If my experience is anything to go by, the Indians take such negotiations even more seriously than the Chinese. In India it is common to negotiate a price even in a regular shop and the negotiation ritual can be incredibly elaborate. One negotiation I witnessed on a trip to India, which was exhausting even as a spectator, lasted more than an hour and included several cups of tea and plates of sweets during which time various store clerks tried to offer me several other items that I didn’t want. So, I wasn’t that surprised when my Indian colleague approached the negotiation with the Chinese stall holder very differently than I would have. Her initial price, remember, was 200 yuan. He counter-offered with 5 yuan. She pretended to be outraged at this grievous insult to her intelligence and reputation (a common negotiation tactic) but, rather than play along, my colleague simply turned and started walking away. The stall holder, knowing she had one last move in the game, shouted out “10 yuan”! My colleague turned around, pulled 10 yuan from his wallet and the sale was made at 5% of the initial price the stall holder had set.

Technically, anchoring bias occurs whenever you allow your judgement to be skewed by one piece of information. Usually, this is the first piece of information. In this case, the first piece of information was an offer of 200 yuan. My colleague simply ignored that and made an offer based on what he thought the item was really worth. This is the best way to get around anchoring bias. In a negotiation, or in propaganda, your judgement is being skewed by information that somebody else gives you. If you have your own independent source of information and understanding, you become more or less immune to the tactic.

To a certain extent, the power and influence of the media is almost wholly predicated on anchoring bias because as readers we don’t have independent access to alternative sources of information. You can verify this for yourself. Every now and then a media story comes along which is about something that we have intimate knowledge about. Usually, this is something related to our job or it can be an event where we were an eyewitness. We read the article and marvel at how badly the journalist got the story wrong. Then we go to the next article and read it as if it is the truth. Of course, that article is just as wrong as the previous one, the only difference is we don’t have our own anchor from which to make sense of it. If I’m reading about the latest goings on in some exotic location on the other side of the planet, I won’t know whether the paper is skewing the information. This is less true in the age of the internet where the information for us to make our own judgement is usually out there waiting to be found. But most of the time we are reading the news precisely because we don’t want to spend the time and energy to verify the facts. We are outsourcing our understanding to others.

Anchoring bias is also a favourite tactic of politicians whose job involves framing issues in their favour. A classic example of this was seen in my home town this year due to the ‘second wave’ corona outbreak in Melbourne. To give overseas readers a lightning overview of what happened, the corona numbers went down all across Australia once the international borders were closed in March. Almost every state got to almost 0 ‘cases’. Then, the numbers started to rise in Melbourne and they shot up to about 700 a day before the government implemented one of the longest and hardest lockdowns of anywhere on the planet which ended up lasting four months before numbers got back to around 0. This was obviously a huge political problem for the government of Victoria . Every other state in the country had got the numbers under control, but not us. There was a lot of political pressure put on the state Premier in particular for some mistakes made in hotel quarantine programs.

Therefore, our Premier had a strong vested interest in making the actions of his government look as good as possible. One of the ways he did this was the use of anchoring bias. Rather than compare the numbers in Victoria to other states in Australia, the Premier kept comparing them to numbers in Europe. Against the former numbers, his government looked incompetent, against the latter, it looked good. One specific example of this was the use of France as the anchor. Apparently France had a daily case rate of about 700 back around the same time that Melbourne did (July-August). By October, our Premier pointed out, France was now at 20,000 ‘cases’ a day while Melbourne was back to single digits. Therefore, he must have done a good job. Compared to France, Melbourne looked like a huge success.

As I mentioned above, the best way to defend yourself from anchoring bias is to have your own anchor or anchors, preferably ones that are based in reality. The reality in this case was that France and Melbourne were completely invalid comparisons. In France in July, people were free to do as they pleased, go on holiday and enjoy the summer months. In Melbourne, people were forced to stay at home with curfews and limited hours outside. Nobody was allowed to travel even outside the city boundaries, let alone to another state or country. France was not even trying to control its corona numbers while Melbourne was pursuing an elimination strategy. So, the Premier’s anchor was completely irrelevant. He was comparing apples to oranges. That didn’t stop it from working, however. Many people parroted the Premier’s claim and believed that Melbourne had done something special. They pointed to France as evidence for their belief.

That’s how anchoring bias works. To be on guard against it, we must be very wary about the first pieces of information we are exposed to on a subject. We should definitely be wary about comparisons that somebody else is inviting us to make. We should look for multiple sources of information from multiple actors. And we should use that unfashionable skill called thinking so that we have our own anchor against which to weigh information.

Reader Exercise

The corona event is a case of anchoring bias on steroids but in a specific and unusual way: there was no anchor!

Most members of the public had never given a single thought in their lives to viral disease and had probably never looked at a single statistic related to respiratory viral outbreaks. All of a sudden they were bombarded with graphs and statistics but completely failed to put those statistics into perspective. The media and the politicians failed to give the public any useful anchors. Whether that was done on purpose or because journalists and politicians also had no proper anchor is anybody’s guess. (Our usual choice between incompetence and malice).

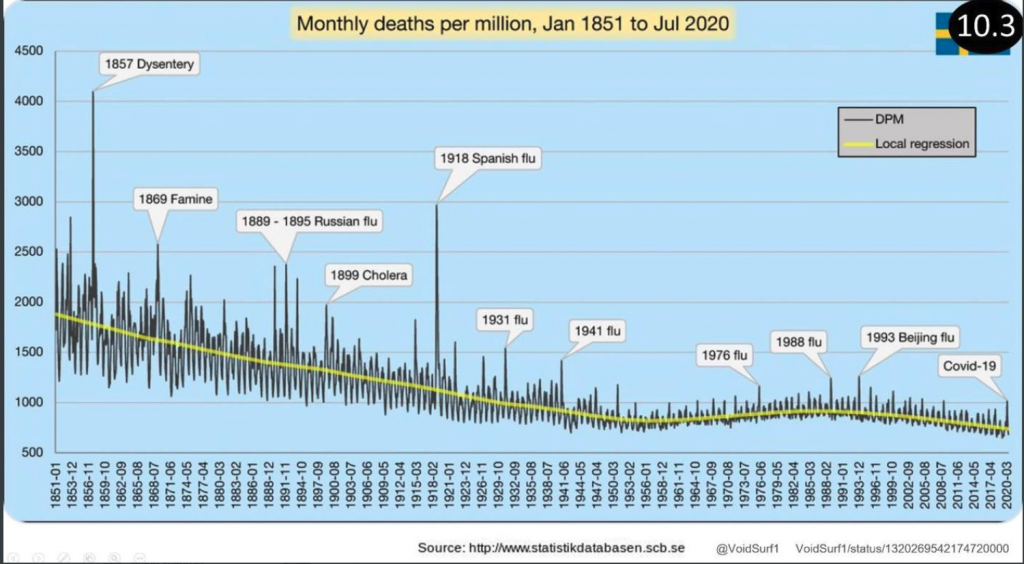

Have a look at the following graph which is an attempt to put the corona event into a larger context. The author has inserted their own anchors to guide your understanding and has used Sweden as the overall anchor because Sweden was one of the only countries not to implement masks and lockdowns and therefore the data cannot be explained away by saying “yes, but if they didn’t lockdown the numbers would have been much higher.”

Consider what anchor this graph is using and how it changes your perspective on the statistics that are shown in the media. Do you agree with the use of Sweden as the comparison point? Do you think this framing of the issue is valid?

It is always good to have multiple anchors so that you can put any complex event into proper context. Try to come up with several other anchors about the corona event that would help put it in perspective. This can include the other statistics we are shown in the media as well as non-numerical and even non-scientific points of view.

Postscript

This series of posts will be a lot more fun if reader can contribute. Feel free to post with any interesting stories of anchoring either from your own experience or something in the media.

All posts in this series:

- Propaganda School: Introduction

- Propaganda School Part 1: Guilt by Association

- Propaganda School Part 2: The Passive Voice

- Propaganda School Part 3: Editorialising the News

- Propaganda School Part 4: Headlines and Taglines

- Propaganda School Part 5: Anchoring

- Propaganda School Part 6: Metaphor

- Propaganda School Part 7: Predicting-the-Future

- Propaganda School Part 8: Appeal to Authority

- Propaganda School Part 9: Buzzwords

- Propaganda School Part 10: Lies, damned lies and statistics

- Propaganda School Part 11: Revenge on the Nerds