One of the noteworthy things about the corona event is how many members of the general public thought the science is ‘on their side’ as if there was a scientific consensus that they were following while their opponents, who were by definition ‘unscientific’, were merely parroting superstition and nonsense. This betrays a lack of understanding about what actual science is. Not having a consensus is the norm in science but it seems most people nowadays treat ‘science’ like some big monolith from which truth emanates. That is certainly the way science is taught in school where the emphasis is on learning what has already been ‘proven’ over long periods of time rather than experiencing the ambiguity and uncertainty that characterises live science. Sad to say, in our society, science has in many ways simply replaced religion as a form of dogma. During the corona event, there have been people referencing ‘science’ in exactly the same way that people would once have pulled a passage out of the Bible to try and win an argument.

I showed in part 5 of this series how little ‘science’ had to do with the actions of the WHO and other players at the start of the corona event. In this post, I want to take a look at the public’s perception of the science as communicated to them through the media. There are numerous, in fact too many, ways to investigate this so we are going to focus on just one: the idea that the virus was ‘novel’ or ‘new’.

As this distinction is primarily a linguistic one, we’ll use a little linguistic theory to help elucidate what happened. To start with, let’s recognise that there’s a distinction between what you can call folk language or natural language and scientific language.

Natural human language is vague and context based. This flexibility is beneficial in everyday life but a hindrance in science where logic and rigor are required. Thus, scientific language tries to remove ambiguity. Words are given fixed meanings and a big part of learning to become a scientist is to learn to use those specific meanings so that disagreements don’t end up becoming endless arguments over semantics.

Because of this difference, the two types of language – folk language and scientific language – actually need to be translated in order to be understandable. The problem is that scientific language uses the same words as natural language and this can lead a speaker of the language to assume they have understood something when in fact they haven’t. Scientific language is a lot more like reading Shakespeare: you recognise the words but the meanings that you assign to them are not necessarily the same ones that people used in Shakespeare’s day.

If you want to understand science as a lay person, you must spend the time really understanding the specific meaning that a scientist is giving to a word. Conversely, as a scientist speaking to a lay person, you must be sure to translate the scientific meaning of into unambiguous everyday language. Of course, translation is a separate skill from doing science and there is no guarantee that a scientist will be good at it.

I’ll take this opportunity to yet again reference Richard Feynman who stated that a scientist should be able to explain their work to a ten year old and, if they couldn’t, it meant that they themselves didn’t understand it. Thus, it should arguably be part of the scientific profession for scientists to regularly explain their work directly to the public as this would be beneficial to both.

Of course, that doesn’t happen. What happens is that the media steps in and ostensibly fills the role of translating science into a form the public can understand. But, as we will see, they failed to do this during the corona event.

A useful way to examine the specifics of that failure is to introduce another concept that’s well known in linguistics: The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis simply states that languages influences thought. The different languages of the world encode different bits of information about the world and therefore in order to speak those languages you will be predisposed to pay attention to whatever information the language requires you to express. Most people have heard about the Eskimos and all their words for snow but there are all kinds of other nuances built deep into the grammar of languages that can theoretically bias thought.

An example of this is that in many Australian Aboriginal languages there are particles to express coordinate directions. Thus, you wouldn’t say “the fork is to the left of the spoon”. You would have to say “the fork is east of the spoon”, or west of the spoon or whichever direction it happened to be. Because the language requires the speaker to encode cardinal directions, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis predicts that speakers of those languages should be better able to identify cardinal directions than speakers of other languages. Cognitive linguists set up a range of experiments to test this and those tests provide evidence that it is true: speakers of Australian Aboriginal languages are more likely to know which way is north, south, east or west at any given time than speakers of other languages.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis was also once used in a court case and it is this example that is most relevant to the corona event because it nicely highlights the difference between folk language and scientific language.

The court case was about a factory worker in the US who had taken a cigarette break in the side yard at the company where he worked. In the yard there were a number of 44-gallon drums that had been marked ‘empty’, which was the signal for them to be collected by the trucking company. Having finished his smoke, the worker thought to make use of one of the drums as a rubbish bin but neglected to extinguish the cigarette before doing so, with explosive results.

The case went to court. The company was charged with negligence on the basis that the sign ‘empty’ was misleading. The lawyers for the man argued that the sign had the connotation of being ‘inert’ or ‘safe’ and that the company was responsible for what had happened because the label they had put on the drum was untrue: the drums were not empty, they were full of explosive gas.

The man’s lawyers won the case.

This might sound spurious and an example of where some clever lawyers tricked the jury on a technicality. But let’s think about it from a scientific point of view. Scientifically speaking, a 44-gallon drum is never ‘empty’. There is a concept in physics of a perfect vacuum but that doesn’t exist in reality. There is, in fact, no actual way to make a drum properly ‘empty’ or ‘vacant’ or ‘void’.

In the case of the worker, the normal contents of the 44-gallon drum were paint thinners and even though the liquid version of the paint thinners had been removed there were still technically paint thinners in the drum, they were just in gaseous form. As the gaseous form of paint thinners is as explosive as the liquid, the company was ruled to be negligent to have labelled the bin ‘empty’.

It turns out that ‘empty’ is a strange kind of word that really doesn’t mean much in physics but we use it all the time in everyday language. In order to understand the meaning of the word ‘empty’ in this specific case we need to understand that natural human language has a number of ground rules that are assumed in interactions. These are not captured in the semantics of the words themselves but they play an important role in the construction of meaning. They are sometimes called implicatures because they are implied by what is said or not said.

Without going into the theoretical details, let’s just say that there is an implied meaning in the phrase ‘the drum is empty’ and that meaning is as follows:

‘The drum is empty [of its usual substance]’.

These kinds of implied meanings happen all the time in our use of language. If I say ‘the fridge is empty’ you assume it is empty of food because food is what is normally stored in a fridge (unless it’s a beer fridge). Another way to say the same thing is ‘there is no food in the fridge’ and that statement is also true. However, you can’t translate ‘the drum is empty’ into ‘there are no paint thinners in the drum’. The second statement is not true. A true statement would be something like ‘there are no paint thinners in liquid form in the drum’.

So, this is not a legal technicality and it certainly wasn’t a technicality for the worker who had thrown his cigarette into that drum. Words matter and it’s often the simplest of words that can trip you up. That is why science spends so much time and effort to fix the meanings of words and ensure there are no implicatures used. In scientific language, we deliberately remove ambiguity so we don’t fall into just the kinds of traps that the worker fell into (this helps us to achieve Feynman’s first principle as outlined in part 5: don’t fool yourself).

Translating science into everyday language is hard and to do it properly often requires just the kind of seemingly long-winded explications that we have just seen. Scientists who speak to the public might try to avoid this so they don’t appear boring or patronising and in fact this was a pattern I saw a lot during the corona event: scientists would often qualify their statements with the phrase we don’t really know.

Here’s just a few examples I saw of this pattern.

There was the case in Canada where somebody got a false positive test. A news report featured a public health bureaucrat who reassured the public that all was well and the tests were trustworthy. Buried down in the second last paragraph of the article, the bureaucrat admitted that she didn’t really know how many false positives or false negatives there were, but that she ‘expected’ the rates were very low.

On a virological podcast, the special guest virologist was firstly asked to explain how we know that the coronavirus came from bats. She prefaced her answer by saying that we don’t really know and that, unfortunately, the phrase we don’t really know was probably going to be true of every answer she gave that evening. Everybody laughed then she preceded to explain what’s become the accepted story about where the coronavirus came from; the one that she didn’t really know was true.

A favourite example of mine was an Australian academic who was asked on tv how accurate the PCR tests were. He admitted that we don’t really know because there is no gold standard test for sars-cov-2 but he expected it was about 70% accurate. The host simply continued on with the program as if that was a perfectly acceptable answer.

The phrase we don’t really know is highly ambiguous. It could mean we have no idea, but here’s a blind guess. It could mean you’re 50% sure or it could mean you’re 99% sure and you’re just being a good scientist and acknowledging that science proves nothing. When used in the examples above, there is an implied meaning in this phrase:-

We don’t really know [but it doesn’t matter]

If I tell you my house is on fire but give no more context, you’ll probably ask me about it because it seems like it should matter that my house is on fire. Houses being on fire is normally a problem in everyday life. But if I tell you we don’t know how accurate the PCR test is, as a lay person you don’t know if that matters because you’ve never done a PCR test before and in fact have no idea how they work. You don’t have the context to understand so you assume that it must be ok. The experts know what they are doing. Unfortunately, in the case of the corona event, this little phrase we don’t really know led to the avoidance of all the interesting and ambiguous science and gave the public an incorrect understanding of that science. What I would have given to hear the journalist just once ask the question: why don’t we really know?

Let’s now turn to the question of the virus coming from bats and let’s look at another pattern I have seen a lot throughout the corona event. In this pattern, a media article’s headline and main argument is contradicted by the contents of the same article. I have seen this a surprising number of times recently but we’ll look at just two articles both of which deal with the notion that sars-cov-2 came from bats.

The first article is from NPR.

The headline reads “Where did this coronavirus originate? Virus hunters find genetic clues in bats” and in the third paragraph we see the claim “Scientific evidence overwhelmingly points to wildlife, and to bats as the most likely origin.”

Of course, this ‘overwhelming evidence’, like so much of the evidence used in the corona event, is genetic analysis. In this case, the key word is ‘origin’ which means something like genetic predecessor. Using techniques of genetic analysis, scientists now believe that the origin of homo sapiens is in a species called homo antecessor. But homo antecessor hasn’t existed for 800,000 years. So, that word ‘origin’ when used in genetic analysis can mean a very long time. The fact that sars-cov-2 originated in a bat virus says nothing necessarily about its ‘newness’. The story told to the public is that the virus jumped from bats in Wuhan, but the genetic analysis cannot tell us that this is what actually happened. In fact, the genetic analysis has a problem because sars-cov-2 is 96% genetically similar to the bat virus and it turns out this probably equates to quite a long time in terms of evolution.

The NPR article includes quotes from a microbiologist pointing out this exact fact: “But that 4% difference [between sars-cov-2 and its bat relative] is actually a pretty wide distance in evolutionary time. It could even be decades.”

Huh? Decades? But weren’t we told that virus jumped from bats in Wuhan?

The microbiologist goes on to claim that there were probably intermediate hosts and that the most likely animal from which the virus jumped was actually pangolins. That’s strange. Why didn’t the article mention pangolins in its title if that was the most likely explanation? We’ll find out shortly.

The article also contains the following statement: “The 2003 outbreak of SARS was eventually traced to horseshoe bats in a cave in the Yunnan province of China, confirmed by a 2017 paper published in the journal Nature.”

This is a stronger claim. They say it was ‘confirmed’. That sounds like there is solid evidence. Let’s have a look at that 2017 paper.

The headline is “Bat cave solves mystery of deadly SARS virus”. The first line of the article refers to a “smoking gun”. Again, the framing of the entire article gives the reader the impression of solid scientific evidence.

But then things start to sound less certain: “virologists have identified a single population of horseshoe bats that harbours virus strains with all the genetic building blocks of the one that jumped to humans in 2002, killing almost 800 people around the world.”

Huh? What exactly are genetic building blocks? You mean genes?

Then we get this phrase: “The killer strain could easily have arisen from such a bat population…”

That doesn’t sound like a confirmation to me. That sounds like speculation. Yes, it could have happened. But where is the evidence that it did happen?

“They sequenced the genomes of 15 viral strains from the bats and found that, taken together, the strains contain all the genetic pieces that make up the human version. Although no single bat had the exact strain of SARS coronavirus that is found in humans, the analysis showed that the strains mix often. The human strain could have emerged from such mixing…”

So, if you rearranged the genome from fifteen different bat viruses you could get the original SARS virus. That’s not a smoking gun. That’s a trial where the judge throws the case out and the lawyers get disbarred for wasting the court’s time. (Apparently it took the scientists in question five years scrounging around in bat caves to get that finding so I salute their determination if nothing else).

In one final irony the article features a quote from another virologist commenting on the research done by the others and for the first time we get a wonderful glimpse of real science at work: disagreement.

“But Changchun Tu, a virologist who directs the OIE Reference Laboratory for Rabies in Changchun, China, says the results are only “99%” persuasive. He would like to see scientists demonstrate in the lab that the human SARS strain can jump from bats to another animal, such as a civet. “If this could have been done, the evidence would be perfect,” he says.”

In other words, can we please get some real empirical evidence rather than speculation based on genome analysis. Interestingly, Tu’s suggestion is a variation on Koch’s postulates except in this case you are trying to infect an animal with a virus from another species.

So, there was no smoking gun. The case hadn’t been solved. Nothing had been confirmed. Why were the journalists so eager to put the bat spin on the story?

Towards the end of the NPR article we are introduced to Peter Daszak, President of the U.S.-based Ecohealth Alliance. Ecohealth Alliance is a non-profit organisation that aims to “improve planetary health for the public good by uniquely integrating health research and conservation”. The NPR article just happens to contain a link to research that was funded by the Ecohealth Alliance. That research aims to show that the viruses in bats could infect humans. It apparently does so by modifying bat viruses in the lab and then seeing if the modified virus can infect human cells. Why is an environmental not-for-profit funding virological research? Apparently it’s to justify their conservation efforts. In Daszak’s words:

“We don’t need to get rid of bats. We don’t need to do anything with bats. We’ve just got to leave them alone. Let them get on, doing the good they do, flitting around at night and we will not catch their viruses,” Daszak said.”

So, it seems the NPR bat story was promoted by an environmental not-for-profit trying to get humans to leave bats and other wildlife alone. Just when you thought the corona event couldn’t get any weirder! Apparently wildlife activists are doing virology these days. A far cry from the hippies of old.

According to Ecohealth Alliance’s website, their “budget has has grown exponentially and, in turn, so too has our staff and our scientific and media outreach”. Media outreach? So, that’s the reason why the NPR journalist had to bend over backwards to put the bat spin on the story.

With media coverage like this, what chance did the public have of understanding the corona event?

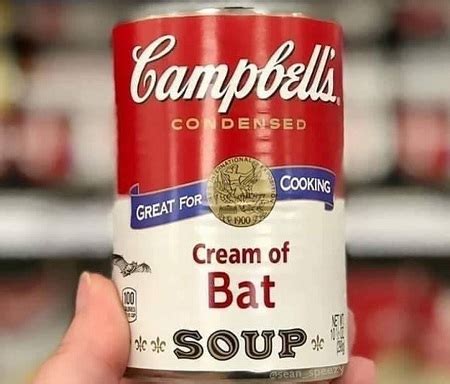

Of course, the bat story was the one that caught the public imagination and if there’s one lesson of the modern world it’s that once something has become an internet meme, the PR battle is over.

So, in the mind of the public, the virus had come from bats, it was brand new to humans and therefore super dangerous. But let’s take a big step back and have one final look at the science.

Buried in that NPR article was a crucial piece of information that had been given by a scientist but ignored by the reporter who was too busy trying to focus on bats. That crucial piece of information is at the centre of the issue because it deals directly with whether the virus was ‘new’.

Recall that the Chinese researchers ran the genetic identity of the ‘new’ virus against known viruses and the closest match was this bat virus which is 96% similar. The microbiologist in the NPR article stated that this 4% probably equates to decades in evolutionary time (other have speculated between 20-50 years). In other words, the closest match we have to sars-cov-2 is decades old. Of all the viruses that humans have identified, the nearest one to sars-cov-2 diverged decades ago. This gives us some insight into a point I made in post 5: we really don’t know much about viruses. If the closest match we have is decades old, then there must be heaps of viruses that we have not yet identified. Which is not surprising because apparently the research funding is given to virologists to hunt around in bat caves rather than testing the general public (although perhaps that’s a very good thing and maybe we should send more virologists to the caves).

Others have realised this problem with the 4% difference. Here is an example of an attempt to save the bat hypothesis by a story of how the bat virus jumped to miners eight years ago and was then transported to the viral lab in Wuhan. It just happened to leak out late last year and cause the pandemic. It’s a nice story, to be sure. It could have happened but, let’s face it, we don’t really know.

There is another hypothesis that is much simpler and doesn’t require bats or pangolins or murky goings-on in viral labs: sars-cov-2 (or some variation of it) was already in circulation and has been for years.

According to this hypothesis, all that happened in Wuhan was that we identified an existing coronavirus. The virus has been in circulation for years, perhaps decades and the Chinese CDC in Wuhan just happened to discover it while investigating some pneumonia cases. Virologists ran off and made a test for it, public health officials put the test into action and ‘infections’ started popping up everywhere. It looked new, but really it had been around for a long time. Just another one of the respiratory viruses that we know exist but we have not yet identified.

There is no evidence that I know of that disproves this (in theory antibody tests could do so but they seem even less reliable than the PCR tests). But there is a very good reason that nobody wants to talk about it because this hypothesis is political and psychological dynamite. It would mean admitting that we lost our heads and panicked for no reason.

Of course, we don’t really know. And we never will know because these hypotheses are untestable. All we can do is speculate.

It is tempting to blame the media for the misleading coverage of the corona event. Certainly articles like the one in NPR should be condemned as obvious fake news. But on the whole I think both the media and the scientists tried to do their best. The simple fact is that the corona event represents a level of complexity that simply can’t be dealt with in single articles or single programs on television. That’s true just of the science behind it but once you factor in the public health response, the politics, the fear among the public, the statistics and everything else we simply never had a chance of making sense of it. We have made our world too complex to deal with and that complexity itself became the danger with the corona event. The authoritarian measures taken by politicians were a way to simplify things back to what we can make sense of. Close the borders. Stop all travel. Stop a large part of commerce. Stop everything because we don’t really know what we’re doing.