As I’ve mentioned before on this blog, one of the most memorable real-life comments I heard during the corona debacle happened over a news story from here in Australia that went viral around the world. A pregnant woman in her pyjamas was arrested and handcuffed in her own home in front of her children. Her “crime”? She had posted on Facebook about an upcoming protest against the corona measures. The memorable quotation came up in a conversation I was having with a family member about the subject who pondered – “Is nothing sacred?”

Is nothing sacred? As I mentioned in a recent post on the subject, sacredness is a complex concept. It includes both the notion of holiness and the notion of danger. Since holiness is related to wholeness and to health, sacredness is also negatively linked to illness, disease and death.

The anthropological literature tells us that pregnant women have been almost universally considered sacred across cultures. The reason is not hard to see since childbirth not only creates new life but has traditionally been incredibly dangerous to the woman herself. Morality rates during childbirth would have been measured in double digit percentages for most societies throughout history.

In modern Australia, there are about 25 deaths per year of women giving birth, slightly higher if you include deaths within a month of the birth. That represents about a 0.005% fatality rate. Childbirth is still dangerous, but almost certainly less dangerous than it has been at any time during history.

Could this explain the behaviour of the policeman arresting the pregnant woman? If sacredness is related to dangerousness, it follows that things become less sacred as they become less dangerous. Now that the danger has been taken out of childbirth, pregnant women are no longer considered sacred. Therefore, they can be arrested and handcuffed in their pyjamas.

Note that this hypothesis also serves to explain the loss of the sacred in general in modern society since we live in what is almost certainly the safest society that has ever existed, not just in a medical sense.

Pregnant women are no longer dangerous (sacred), but apparently what that particular pregnant woman was doing was. It might sound ridiculous to think that posting on social media is dangerous. But, in the eyes of those who believed the official corona narrative, such posts were dangerous because they had the potential to be, well, infectious. A well-crafted social media post is potentially even more infectious than a coronavirus.

Social media posts are politically dangerous. Don’t believe it? Consider that many of the colour revolutions we have heard about over the last decade or so were organised and broadcast through social media.

If social media posts are dangerous, does that make them sacred? The question sounds absurd. Millions, if not billions, of social media posts are generated every day. Nothing seems cheaper than a social media post and, whatever the sacred is, it is not cheap.

Sacred rites are traditionally highly involved and time consuming. The initiate is made to work hard to get through. This is not merely done for effect. It mimics a truth about the real world which is that many of the most rewarding things in life do require hard work. That’s why sacred rites have traditionally included long pilgrimages and other tests of endurance and stamina.

Social media posts cannot be sacred because they are way too easy. Click a few buttons on a mouse and a keyboard and you’ve got yourself a post. Because it’s so easy, it encourages impulsive behaviour. How many times do we see somebody post something on social media only to delete it minutes later? Social media seems custom designed to appeal to our lower natures, not our higher (sacred) ones.

It seems that most things that go viral appeal to our lower nature. A philosophical treatise, a beautiful poem, a brilliant novel or symphony or some theological wisdom, these do not go viral. What mostly goes viral is death, destruction and debauchery.

We saw a prime example of death and destruction in recent weeks with the killings in Israel, graphic images of which spread around the internet in just hours. Sadly, that is nothing new. TV news has been full of those for decades, albeit probably not as explicit as the ones we saw. But then something happened that, if I’m not mistaken, was new.

In the days immediately following the bloodshed, we saw what can only be called celebrations on the streets of many western cities. These too were broadcast via social media and the internet. I’m not saying that the killing of civilians is new. It may even be that people cheering on the death of civilians is not new. But such scenes would never have been broadcast on commercial news networks in the days prior to the internet. Therefore, our exposure to such images is new and we can thank the internet and social media for bringing them to us.

No doubt there were many different reactions to the images of the killing and then the images of the cheering. One strong thread that I noticed was an outpouring of what we can call, without hyperbole, despair. This despair was not just limited to the ungratifying sight of watching fellow humans cheer on each other’s deaths. Rather, it was about Western civilisation itself since the images of the cheering were not coming from somewhere foreign and exotic but right at home including some of the most famous landmarks of the West.

I’ve seen several posts from public intellectuals over the last week with an almost mourning tone predicting the end of western civilisation as a result. For these people, a line was crossed and I think we can call that line the sacred. It’s a similar line that was crossed for some of us with the corona lockdowns. Things that we had believed to be fundamental (sacred) to western civilisation turned out not to be so.

Interestingly, the people despairing this week were mostly, as far as I could tell, people who were in favour of the corona measures, which just goes to show that what is sacred differs from person to person. But we can generalise a trend that has been pickup up steam for at least a decade now in the West: the destruction of the sacred.

Whatever side of the conflicts in the Middle East you happen to be on, celebrating the deaths of civilians is heinous (Note: I’m talking here specifically about the western perspective on the matter, not the perspective of the various peoples involved in the actual conflict). Doing so in front of some of the most famous monuments of western civilisation does give the whole thing a civilisational collapse vibe. What sort of society allows people to celebrate the slaughter of others in front of its most famous monuments? The answer is: a society that has lost all notion of sacredness.

This loss of sacredness in the West is not a new thing. It’s been going on for centuries. What is sacred is what is dangerous and what is dangerous is what is powerful. Gods are dangerous and powerful, therefore they are sacred. Kings allowed themselves to be anointed by Popes since being sanctified increases one’s perceived authority which helps to carry out the job of being the boss.

The destruction of the sacred in the West began with the Reformation which did away with the authority of the Pope. It’s no coincidence that shortly thereafter kings started getting their heads chopped off. Authority and sacredness have always been linked. The rejection of authority began with Luther, continued through the British Civil War, the French and US Revolutions and ends up with us today.

Note that this lack of authority is built into the very structure of the internet. The internet is designed to be decentralised. It will continue to work even when important (well connected) nodes get taken offline. Thus, the whole point of social media and the internet in general is that there is no authority. This is another key reason why the internet cannot be sacred.

The internet might be the culmination of a trend that’s been in play for centuries. The inalienable right to free speech means that the government does not get to stop you from saying something. That means there is no authority to uphold standards of behaviour. There are positive things about that but there are also negative things. It means that nobody will stop people going into the street and cheering at the death of others.

Almost by default, free speech removes the sacredness of speech. For something to be sacred, there must be danger but also redemption and closure. There must be consequences for action. If you get to say whatever you like and there are no consequences, then your speech is not sacred. For most of history and across cultures, the consequences to speech were ultimately vested in the power of authority. Authority could provide closure and return the situation to wholeness, health and holiness.

Without authority, things cannot be made whole (holy) again. Thus, when behaviour crosses a line that people consider sacred, there is no mechanism to bring things back to equilibrium. The result is modern society where all kinds of things that cross the sacred line are left unhealed. For some it will be the sight of people celebrating death, for others it will be the corona lockdowns and forced vaccinations, for yet others it will be the sight of grown men dancing naked in front of children.

The common thread from the last decade or so is that we are seeing all remaining notions of the sacred go up in flames in front of our eyes. What constitutes sacredness might be different for different people. But it seems that everybody has a target on their back at the moment and some invisible grim reaper is sharpening his symbolic scythe ready to destroy whatever it is we consider sacred.

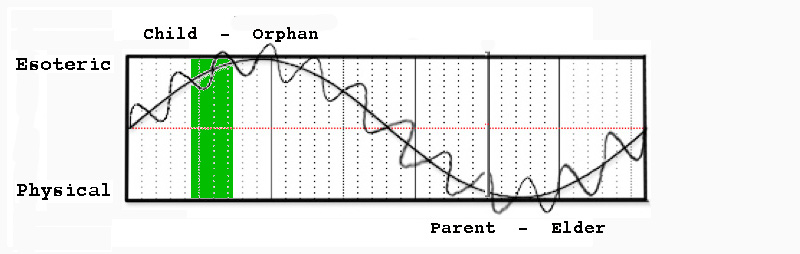

The trend does seem to be going into overdrive at the moment. But it is not new. One of the earliest thinkers who saw the profound challenge that the loss of the sacred entails was a philosopher I’ve mentioned here many times, Soren Kierkegaard.

Kierkegaard’s insight is more impressive because the society he lived in still had the outward forms of the sacred. People in his day still kept up appearances. What he intuited was that people no longer really believed in the sacred and the ramifications of this were just starting to appear in the first half of the 19th century.

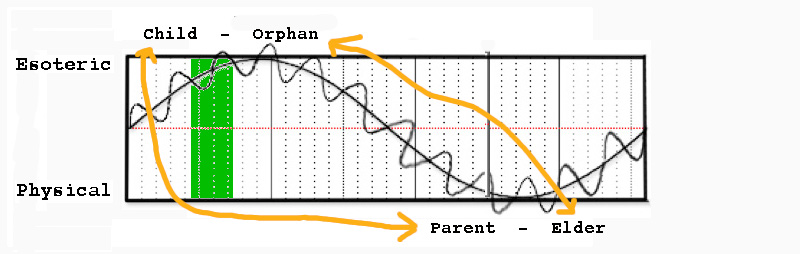

Kierkegaard called the process of the destruction of the sacred the Great Levelling. All authority, all regulation of behaviour, all discipline, all belief in the elevation of individuals of worth, all of the things considered sacred previously are going away. Since these attributes have also been synonymous with the concept of civilisation, it makes sense that some people believe the process represents the end of civilisation.

History is full of examples of elites who abused their authority and subsequently lost the trust of the public (and often their own heads into the bargain). The Great Levelling is not about that. It’s not about institutional corruption per se. Kierkegaard saw it as an impersonal process that was happening across the board and was not limited to any particular social class.

We should remember that Kierkegaard was writing at the time when the cult of Napoleon had imploded. Napoleon had been a prime exemplar of the notion of the great man of history; the hero who could turn the tide of civilisation through will alone. Among other things, his defeat called that understanding of history into question. The feeling of the loss of authority not just as the loss of the sacred but also as the loss of civilisation began around this time as the pessimist and nihilist movements got going.

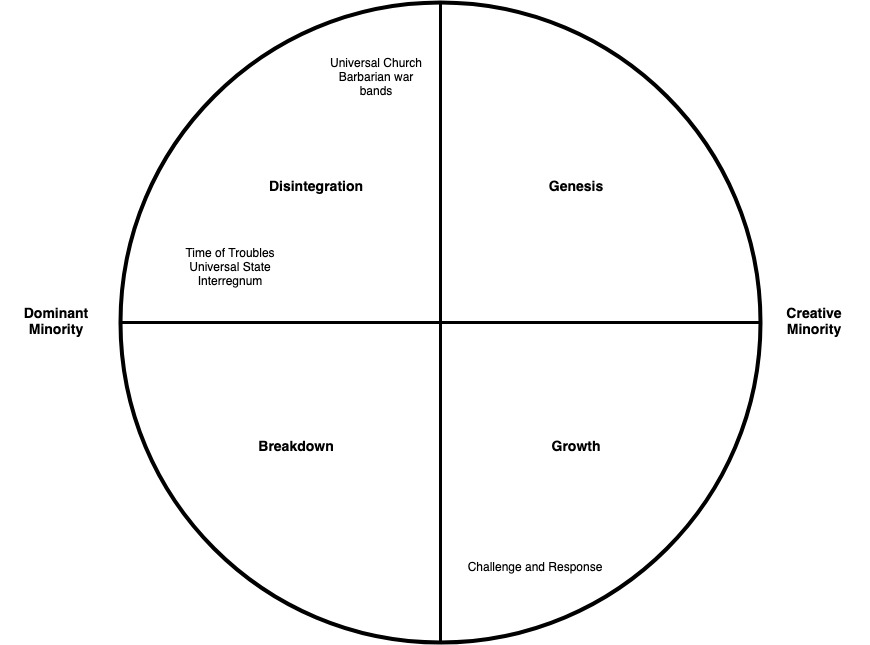

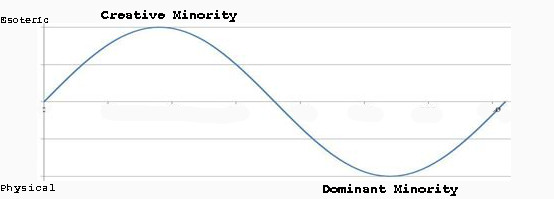

Can it be a coincidence that it was also at this time that the alternative analysis of history as a set of impersonal forces came for the fore? Hegel, Marx, Spengler and Toynbee all followed. Kierkegaard’s Great Levelling is another example of an impersonal historical force. He describes it this way:-

“No single individual (I mean no outstanding individual – in the sense of leadership and conceived according to the dialectical category ‘fate’) will be able to arrest the abstract process of levelling, for it is negatively something higher, and the age of chivalry is gone…

The abstract levelling process, that self-combustion of the human race, produced by the friction which arises when the individual ceases to exist as singled out by religion, is bound to continue, like a trade wind, and consume everything…

the younger man …realises from the beginning that the levelling process is evil in both the selfish individual and in the selfish generation, but that it can also, if they desire it honestly and before God, become the starting-point for the highest life – for them it will indeed be an education to live in the age of levelling.”

Now, we might say that Kierkegaard’s Levelling is nothing more than the inevitable historical force that Spengler and Toynbee would later identify as the decline of civilisation. But Kierkegaard was a scholar of the ancients and made an explicit distinction between the levelling of our time and ancient Rome. Rome had its Caesars, its heroes and great men, all the way up til the end. The Great Levelling explicitly seems to negate the Caesar, as the failure of Napoleon had shown in Kierkegaard’s time.

Kierkegaard’s vision is almost identical to the one that Dostoevsky later presented in The Brothers Karamazov. The only way out is through. The age of levelling is going to destroy all authority and all sacredness. For those able to sit with the spiritual nausea of it, there opens the possibility of a new religiosity born out of the explicit denial of all the theoretical abstractions that the modern world is full of. It is a childlike reconnection with immediate experience. This idea, in different forms, can be found in many other thinkers of the last couple of hundred years.

The Brothers Karamazov is a description of what it means to experience the Great Levelling and come out the other side. Alyosha must face the lies and hypocrisy of religion. Ivan must face the abyss that is the abstractions of modern thought. Dmitri must face the corruption of the state. They are each forced to deal with the destruction of what is most sacred to them.

For Dostoevsky and Kierkegaard, religion, philosophy and the worship of politics only separate us from the truly religious. With the death of religion in the West, many have sought to avoid facing the Great Levelling by escaping into abstract thought or politics. That is partly what is behind the hero worship of a Napoleon, a Hitler or a Trump or the worship of abstractions like dialectical materialism. It’s also behind the desperate desire to “trust the experts”.

Even in somebody like Spengler, who was one of the most insightful analysts of the modern West, we find the desire for Caesarism and the return of authority to set things right. Spengler’s comparative history propagated the levelling process and yet he seemed to be simultaneously repulsed by it.

Of course, the levelling process is repulsive. That was Kierkegaard’s point. The internet and social media might represent the final stages of the Great Levelling since they seem tailor-made to force us to confront the repulsion that comes with the destruction of what we consider sacred.

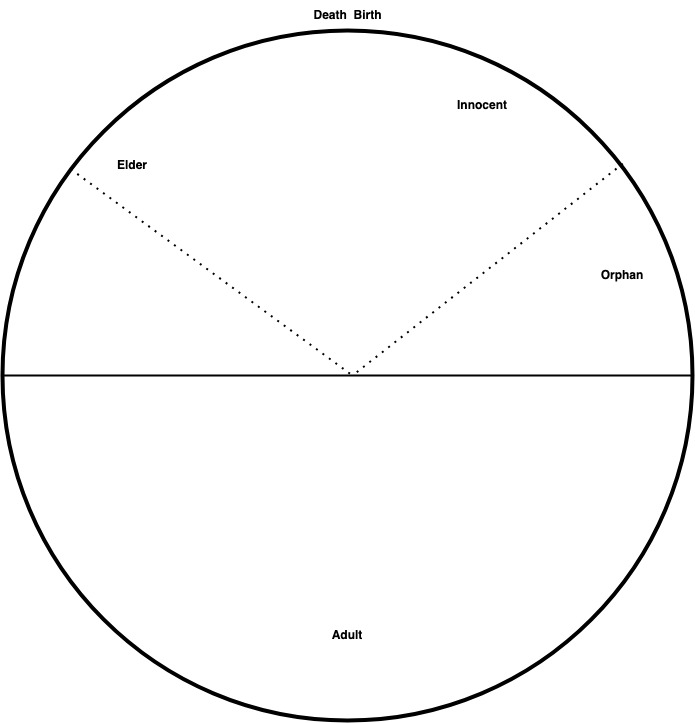

What both Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky believed was that to face this repulsion directly would give birth to something new. All past civilisations have been predicated on heroism, authority and the sacred. They have been run by what we call the elites. The Great Levelling forces a radical equality and freedom. Since this is the opposite of what we have hitherto called civilisation, it looks indistinguishable from the end of civilisation. Maybe it is the end of civilisation. But maybe Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky were also right and it is, in fact, the birth pangs of something new.