The reference to Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement in last week’s post reminded me of a hypothesis that occurred to me some time ago as a way to explain part of the current state of public debate in western countries. Dr King saw the civil rights movement as having two stages for success. The first was equality before the law and King was quite clear of the limitations that the legal approach entailed. You cannot legislate for everybody to love each other, he said, but you can legislate so that people do not hurt each other.

The second part of the civil rights movement included reference to the spiritual teaching that could at least strive to have everybody love each other. But it also aimed to address historic economic inequality through training, education and employment opportunities. Dr King called this economic justice. The idea was that poverty, ignorance, social isolation and economic deprivation would all be fixed by creating employment for all.

To this day, we think of these two approaches as intrinsically related. There are still attempts to address various inequalities through legislation and other attempts to address it through what we might give the generic title of social programs. However, these two approaches are qualitatively vastly different.

Legislation presents us with a crystal clear outcome. You either have the right to vote or you don’t. There is either a law for equal pay for equal work or there is not. Because the outcome is binary, when the outcome is achieved you can throw a big party and celebrate because you and everybody else know that you succeeded in your mission.

Viewed this way, the main legislative goals of the civil rights and feminist movements had been achieved by the late 60s or early 70s at the latest in most western nations. That led into the second stage of the program; namely, programs to address poverty, ignorance, social isolation and economic deprivation.

There’s a lot that can be said about all that but I want to focus on a single point which is that the second stage of the program involves a shift from legislation to systems. We can use a computer programming analogy to elucidate this.

Legislation is the equivalent of computer code. You either have code or you do not. But the fact that you have it does not mean that the code will run. For that to happen you need a system. This includes a computer, the computer’s operating system, the runtime environment including all the other programs that the program you wrote relies on and whatever peripheral objects interact with the computer such as mouse and keyboards.

If the program interfaces with the internet, the system now includes all the things that make the internet work. Then we have all the people involved including those who will use the program for its intended purposes (the users), the government agencies who manage the regulatory environment that the program operates in, the malicious users who want to subvert the system for their own ends etc etc. All these make up the system within which the code runs.

The same is true with legislation. Governments might pass laws but those laws are only put into action through the bureaucracy including the courts, lawyers, judges, police, administrators and all the people who implement the law. Thus, even though you have the legal right for something, that right only matters if the system decides to uphold it. Over the last three years, all kinds of legal rights were thrown out the window because the system decided it was going to ignore them. Arnold Schwarzenegger summed it up best by going on television and saying in his inimitable vocal style “screw your rights”.

Legislation requires a system to enforce it just like a computer program requires a system to run it. However, the passing of legislation is a simple fact with no ambiguity. But the goal of fixing poverty, ignorance, isolation and economic deprivation is far less clear because these are not the laws that generate the system but measurements of the system. Poverty is the outcome of a system. In order to talk about it, we must first agree on its meaning and the reality is that there are no objective meanings for concepts like poverty, ignorance and inequality.

Let’s take two pertinent examples from recent history. Assuming the existence of a disease-causing virus, what number of cases and what Case Fatality Rate (CFR) are required before we declare a “pandemic”? There is no objective answer to this question. Some people will say 0.1% CFR. Some will say 1%. Some might say 5%. Some might say that a single fatality is unacceptable and the whole world must be shut down until such time as scientists figure out how to prevent anybody from dying.

The same goes for vaccines. There was a time when a handful of deaths from a new vaccine would stop the rollout. Now we declare a vaccine safe and effective and give it official approval with orders of magnitude more fatalities and side effects. One of the reasons this can happen is because there is no objective measurement. Some people will say that no fatalities and side effects is the definition of safe and effective. Others will accept different numbers of fatalities and side effects.

Thus, even when we attempt to define specific measurements to nail down the definition of seemingly simple concepts such as “poverty”, “inequality” or “pandemic”, we have the inherent problem of subjectivity to deal with. That’s the problem with trying to measure systems. But that’s just the beginning of the fun.

All measurements have an error rate. The great German mathematician and astronomer, Carl Friedrich Gauss, is credited as being one of the first to realise that astronomical measurements were never exactly the same but had to be averaged out as a kind of best guess. If that’s true of a relatively simple measurement like the position of a star in the sky, how much more true is it of biological or sociological measurements involving hugely complex and constantly adapting systems?

How accurate is the Case Fatality Rate, for example? Well, first we have to understand that this statistic combines two separate measurements: the case measurement and the fatality measurement. So, we need to know the error rate from the PCR test which defines a case and the error rate of cause of death analysis. In relation to the latter, blind autopsy tests have shown that the cause of death written on a death certificate is wrong about 1/3 of the time. Assuming a 10% error rate in the PCR test, you’ve got 10% error multiplied by a 33% error and that’s before you get into errors caused by other parts of the system such as when hospitals are incentivised to find “cases” and causes of death because they get extra money for doing so.

So, we have a problem of defining which measurements to use, what those measurements mean, and what is the error rate of those measurements. But even if we agree on a relatively well-defined measurement and we are pretty sure of its accuracy, focusing on just that measurement to the exclusion of all other measurements can lead to pernicious outcomes. The more complex the system, the more of a problem it is to focus on just one measurement. Let’s elucidate this idea by modifying an example pointed out by Frederic Bastiat about a hundred and fifty years ago.

Your nation’s economy is not growing according to the latest GDP statistics. How are you going to kickstart it into action? One way is to break windows. Pay a mob $50 each to go around throwing bricks through plane glass. Not only will the mob’s income go up, but window repairers in the nation will see a boom in business. Voila! You have now increased GDP. But only a fool would believe that the economy got better. That is the problem with relying on only a single metric. Metrics can be useful but you have to know what your metric does and does not measure.

Taking the last two points we can formulate an iron-rule of politics: the measurement of systems can and will be gamed if the incentives are in place to do so. And the gaming will include the choice of measurements, the definition of them and the way in which they are gathered. Let’s take another example from economics to explore just the first concept in the list.

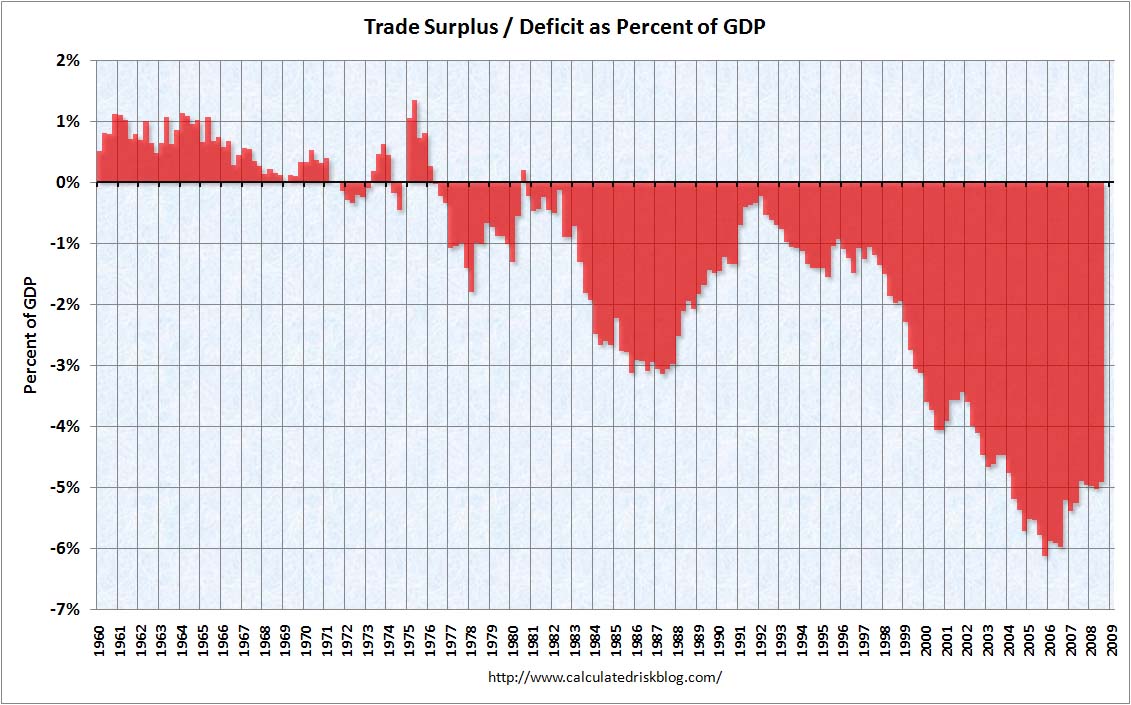

John Maynard Keynes pointed out three quarters of a century ago that persistent trade deficits (or surpluses) will eventually ruin a country. So, you’d think that the trade deficit figures would be an important metric in the public debate, right? Perhaps it was once upon a time, but not anymore. Why?

As the graph on the right shows, the US has been running trade deficits for about five decades. No coincidence that those deficits began around exactly the time that the gold window was closed in 1971. Trade deficits are the price you pay for having the global reserve currency. But there are winners and losers from that system.

The losers are the companies in your country that manufacture things. They’ll get screwed. On the upside, you’ll get cheap imports from other nations who are running a trade surplus. The banks and financiers will win because your nation has the reserve currency and somebody has to facilitate all the trading of financial tokens. Thus, banking and other “service” jobs will rise at the expense of working class jobs. There are a number of other side effects, but these are the main ones and we can clearly see that this is exactly what has happened in the US since the early 70s.

(As a side note, when Trump said he was going to bring manufacturing jobs back to America, that could happen but it would reduce the trade deficit and would almost certainly require the US to give up its reserve currency status. Whether Trump knew that is anybody’s guess but it certainly explains the utter terror he struck into the hearts of all the people who benefit from the status quo).

Keynes noted that persistent trade deficits will lead to internal political strife and eventually crash the economy if allowed to go on. He wasn’t just basing this on theory but on real world evidence from prior to WW2. If he was right, then a persistent trade deficit is a grave danger to a nation. We don’t hear about any of this, of course, because the people who benefit from the system use some of their profits to ensure the trade deficit metric and associated consequences never makes the news. That’s one way to game the system with metrics.

This leads to a final point. It’s tempting to say that those people are corrupt and are using the system for their own gain at the expense of others. But for really complex systems, few people are willing and able to see beyond their perspective. (In more philosophical/theological language, we might say that only God can see all perspectives).

We can put the same idea into more neutral language and say that everybody has a different perspective on the system. This relates back to the earlier point about there being no objective measurements of systems, only subjective ones.

In relation to corona, for example, it was clear to me from the earliest statistics that the virus wasn’t a risk for myself. But, if I was thirty years older, overweight and had diabetes, then the story would have been very different. That alternative me would have been looking at the same set of measurements, the same system, but would have drawn very different conclusions.

Same with the trade deficit measurement. If you’re a manufacturing business or somebody trained to work in a manufacturing business, the trade deficit figure is a disaster. If you’re a banker or a consumer, it’s good news since it means lots of profit for the former and cheap consumer items for the latter. Same system, different perspectives.

Now, we might argue that it is the job of government to weigh up all these different perspectives and do what is right for the country but even here there is a problem because who gets to decide what is right when there are multiple incompatible viewpoints?

Let’s take the trade deficit issue. Although history shows that persistent trade deficits inevitably lead to bad outcomes, this is not a logical necessity. If one country wants to run a persistent trade deficit and other countries are happy to run a corresponding persistent trade surplus, they may do so indefinitely. What inevitably upsets the apple cart is politics and so governments are always tempted to simply suppress the perspectives that go against current policy. In fact, that’s what always happens and what always has happened.

Putting all this together we can see that dealing with systems is far more complex and challenging than dealing with legislation. Wherever there is complexity and ambiguity, there are people with questionable motives who are willing to use it to their advantage. But even people with good intentions suffer from the fact that complexity usually means that the relation between cause and effect is not clear. There is an inevitable temptation for those who make their living from the system to tell little white lies which over time become bigger and bigger lies.

This brief survey gives us an insight into why the second half of the civil rights and feminist programs have gotten stuck in the mud. What was implied by those programs was perhaps something that has never been achieved before. For most of history, humans have developed systems in a receptive fashion. We found ourselves in an environment and we found a way to make the most of it. Through trial-and-error, we developed what we call culture, which is a set of adaptations to an environment.

To try and create or change a system in an active fashion is incredibly difficult. Every new business venture is an attempt to create a new system and we know that very few business ventures survive for any significant period of time. What is true of business ventures is just as true of government programs but the latter is part of the system of politics and therefore subject to the rule cited above that all measurements will be gamed if there is incentive to do so.

Quantum physics found that you cannot remove the observer from the measurement. If that’s true in physics, its ten times more true in the far more subjective world of politics. Systems are complicated enough by themselves. Once you add humans emotions and politics into the mix, they become exponentially harder and when you scale the system up to the size of a modern society, well, you find yourself in a hall of mirrors. Which is pretty much where we are right now.

“Now, we might argue that it is the job of government to weigh up all these different perspectives and do what is right for the country but even here there is a problem because who gets to decide what is right when there are multiple incompatible viewpoints?”

A king maybe? I think one of the arguments raised by libertarians against democracy was that a dynasty would care about a country longterm while politicians only look until the end of their term (or even only after their election).

Otherwise, I completely agree that the own perspective is a major influence on how you evaluate the outcome of systems. For example, I would say that poverty is a non-issue in Germany, as you get enough money for free to become really fat. They are currently removing the last duties that were related to getting the money (e.g. going to the employment office regularly to check whether there is an employment opportunity).

Social justice is another topic, where you will never get any agreement. When is social justice achieved? No wonder that all these terms ring so hollow.

In general, I have the feeling that a lot of systems don´t work really well in Germany anymore. Even the legislation seems to get worse, as the government seems to be using the legislation to suppress the opposition and also using different scales of justice depending on who is convicted (e.g. an imigrant being acquitted of rape due to him thinking that this was normal sex while alleged “Nazis” are convicted for voicing their opinion about the government).

Secretface – kings are great if you get a good one and awful if you get a bad one. I doubt kings ever amalgamated different viewpoints. They just had the power the make people shut up and do it “for king and country”.

There’s a lot of welfare rorting in Australia at the moment, too. Funny thing is, companies can’t get anybody to work. So, rather than fix the welfare rorts we are increasing immigration to bring in workers at the same time that there’s a huge problem with a shortage of housing. So, yes, the system in general is not working anymore. We can’t even get the basics right let alone worry about giving consideration to different viewpoints.

I think one of the issues you touch on there Secretface is Imperial centralisation and concentration of power. When we think of European Kings we think of power, but for most of the Middle Ages and especially the feudal times kings were pretty weak. It was a constant negotiation with other nobles and was more of a figurehead position that was fought over rather than a solid institution.

It’s only later on in the early modern period of European history that the monarchy becomes powerful and starts sucking in everything in to itself in the imperial fashion, and what is interesting is that it was often those outside the actual monarch that worked to strengthen it (like Richelieu in France), and then in the 17th century the monarchy starts to become synonymous with the Imperial State itself. This signals the doom of the monarchy as it is now superfluous to the State, (cue the beheading) and only functions to appeal to the Faustian love of duration.

So when we harken back to kingship perhaps what we are pining for is decentralised power rather than a monarch itself. A bad king in the Middle Ages had to take on a whole heap of other powerful nobles that checked his power, whereas now who can muster anything against our imperial massive fusion of state and corporate power? Empires represent the most centralised power structures imaginable.

This leads to all the ridiculous problems we see now where legislation does not match reality and orders given far off make no sense locally. Everything is a resource to be sucked into imperial power centres. Where I live the state government is slamming through massive electrical grid structures with no consultation with locals, spending billions on what will be a gigantic white elephant due to the fact it won’t work, while the towns adjacent lie broken from recent flooding, with locals homeless.

Skip – out of curiosity, what are they building in your area? I assume it’s transmission lines?

Yeah not far to the west is the planned route, apparently going ahead in a few months but it’s all very murky and confusing.

Skip – I noticed recently that a solar farm was built not far from where I grew up. Bearing in mind that the Liverpool Plains has some of the best agricultural soil in the country. But who needs food?

https://gunnedahsolar.com.au/project-update-solar-farm-completion/

You grew up on the Liverpool plains!? That and the darling downs is the holy grail of agricultural soils in Australia. That and a small patch near of black prairie soil near Nimmitabel on the Monaro.

It never seizes to amaze me how they have convinced people that giant industrial projects, serving giant consuming cities, built on the back of slave labour and environmental vandalism all over the globe, are somehow ‘green’. And are in fact more green than rolling fields of pasture dotted with livestock and trees, and must go ahead despite what any locals might think.

Yeah, I went to primary school in Boggabri and Narrabri. Beautiful country around there. It’s mostly dead flat but you get all these hills that poke up seemingly out of nowhere. Maybe the tops of old volcanoes.

I guess the cities have always been parasitical on the land. Now that the cities have decided they think electricity is more important than food, the land will be made to provide. Reminds me of the updated Maslow hierarchy.

I once saw a firsthand example of how this complexity related fuzziness can manifest in even the smallest of systems.

I once worked as a salesman in a camping supply store. The other staffers and women were mostly competent salesmen and good workers, but there was one saleswoman who teneded to avoid doing any work by offloading her tasks to the other workers at the store, and she did not make much sells either.

Yet her sales commision was always high. So were her sales numbers. It turned out she spent a large portion of her shift shopping at the store (after all, she was not working much so she had the time), putting all sales to her name.

And the funny thing is that not even one person in the store system benefited from this gaming of metrics. The other salesmen had to do more work, the customers had less help from the staff, and she probably ended up spending more money than she made working there in the first place. Even the store manager is hurt, seeing how he has one employee who did no work, but he still needs to pay, while the money she spent at the store mainly goes to the chain anyways.

Perhaps comedy was invented by wiser people who long ago observed those situations in their own societies and wanted us to appriciate the irony.

Bakbook – it’s a fine line between comedy and tragedy. If it was a comedy, that woman would get a promotion for being the “best salesperson” and end up running the company. But I’ve seen similar stories end badly. It’s precisely because it’s so trivial and silly that she’ll get away with it until she is broke. I once knew a woman who was stealing just a little bit from the company payroll each week. By the time they caught her, she had stolen a very large amount of money and suddenly a silly little thing became a huge problem. Actually, that’s another property of complex systems. Seemingly trivial “causes” can have massively disproportionate effects.

Simon – Luckily for her she was fired very soon afterwards, but for different reasons.

This amplification of random noise is actually fascinating, because it is arguably not just a side effect but one of the core mechanisms that give a complex system its “complexity” in the first place.

In Physics for example, we commonly model complex systems using the language of mathematical systems theory, which is a fancy way of saying “telling stories with systems of nonlinear equations”. One such story is the one of the Turing Patterns. Allan Turing wrote down a system of equations that was originaly meant to explain the emergence of patterns such as the ones seen on the fur of a tiger, but still serves as a model that demonstrates the tendency of complex systems to self orginize, a core chareteristic of complex systems in general.

What’s interesting is that while the model is wrong (biologists now have different theories about how the tiger’s fur pattern emerges), there is something to learn from looking at the dynamic that over time leads to the emergement of the stable pattern in the model system.

The particular nonlinear system Allan Turing wrote has a quality that causes it to amplify a specific range of frequencies over time.

If we introduce even an infinitesimal random perturbation to the system, which could represent noise found in any real world system, very soon at least one frequency which the system amplified via a positive feedback loop will emerge, since a noisy signal has a broad spectrum. This then causes a whole cascade of secondary effects, leading to the emergence of a Turing Pattern.

This process where the system is unstable (every small perturbation causes it to change state), until it transistions to a more stable state (a Turing Pattern) is integral to complex systems, and at least in this nodel, the mechanism is none other than random noise that gets amplified for trivial reasons (The frequency that started it all is unimportant, it was an accident of the noisy enviornment).

Bakbook – very interesting. Would that work in music? I mean, could a similar process produce a Turing Pattern from audio noise and would it resemble music or at least a specific note?

Simon – Sorry for the late response, I was in a place without internet access for the last couple of days. To my understanding this is not only possible, but every time you hear a cymbal for example, you are essentially hearing random noise turning into an ever more complex cascade of frequencies, which gives the cymbal its distinctive rich sound.

I see no reason why one would not be able to do the same thing with an audio signal, but can not think of an example of this being done. However, Nonlinear circuits are used as amplifiers for example, which take advantage of the feedback loops possible in a complex system.

Bakbook – gotcha. I’m pretty sure the same thing happens with distorted guitar amplifiers. The history of that is that some guitarists were using either really crap or damaged amps and realised that they produced an interesting sound. The whole of blues, rock and metal is based on the results. I’m pretty sure that amp distortion would also classify as a non-linear process. So, maybe rock music is “complex” after all 😉