I did say that in the next post in this series we would be looking at the broader meanings around the phase of life called adolescence (aka the Orphan archetype in archetypology). However, it occurred to me that I wasn’t clear enough in the last post about the reason why the Netflix TV series Adolescence represents an inversion of the literary tradition of Western culture. That literary tradition also has strong connections to the Christian theology. Thus, it’s not a surprise to find that both the literary tradition and the theological tradition came under attack in the 19th century as the state set out to disintermediate the church. That process was completed during the two world wars. As part of it, the state finally achieved independence from the church in the creation of propaganda.

While entertainment and literature were still part of the private sector/market, the propaganda of the state was largely confined to overtly political matters. But the line between propaganda and the “arts” has become well and truly blurred in recent decades with ideology and propaganda increasingly being inserted into nominally free market works. The TV series Adolescence belongs to a relatively new trend that’s been picking up steam in the last decade for nominally artistic works to be nothing more than vehicles for ideology. The result is “literature” and “art” that no longer resembles the Western canon. In fact, it is the inversion of that canon. In order to understand this, we first need to be clear about what the Western literary tradition is.

The seminal text on understanding the underlying structure of stories, and therefore the basis of literature, is still Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With a Thousand Faces. Campbell gave the structure of stories the name of the hero’s journey. Every story can be thought of as a cycle where the hero returns to the same state in which they started. Campbell was inspired by the work of Carl Jung, and so he used the Jungian categories of consciousness and unconsciousness to describe that state change. A story begins with the hero living in their normal, everyday life where they are fully conscious of what is going on. They must then go on a journey that requires them to leave a world they understand and step into one they don’t; hence, a journey into the unconscious.

This is a perfectly valid way to look at it, but there’s a higher-level concept that better captures the meaning of the hero’s journey. Stories are about sacrifice. The reason why we care about the hero is because they are laying something on the line, something that is important to them. Our empathy with the hero rests on this fact.

However, neither the hero nor the audience can know the true meaning of the sacrifice in advance. Thus, the hero’s journey is also a journey of understanding. Every story involves the hero agreeing to a sacrifice they do not fully understand and then learning what it means as they live through the consequences.

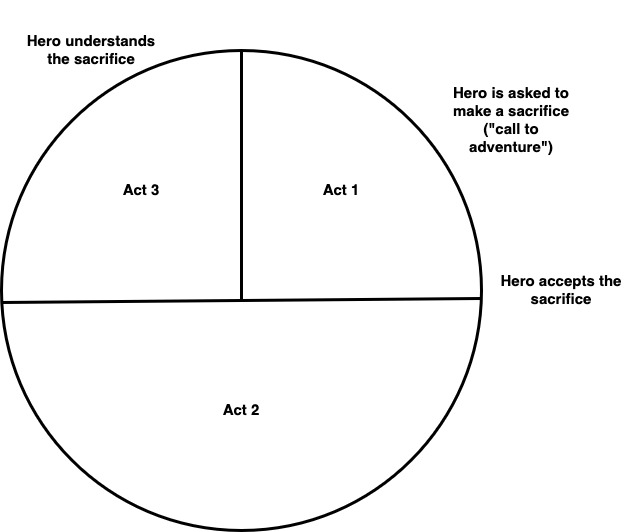

We can diagram this as follows:-

It follows from these considerations that the first and most important question to ask about any story is, “What is the hero sacrificing, and what do they think they are getting in return?” For example, in the movie The Matrix, the character of Neo must leave the matrix. Clearly, it’s not going to be an easy journey to leave the only world he has ever known and step into one he is barely aware of. The sacrifice in this case is potentially his own sanity and maybe even his life. He is willing to make that sacrifice in order to learn the truth about reality. But he can’t fully understand what that means until he has actually taken the journey. Again, that is why we say that the hero can only be partly conscious of the nature of the sacrifice they are making. Full consciousness only comes at the end of the story.

It’s important to understand that this dynamic is not just about fiction; it is very much a part of what it is to be human. Our lives are full of stories, which is another way to say that our lives are full of sacrifices. Let’s say you have a job you are more or less happy with, and then you get offered another job. Maybe the other job seems more interesting. Maybe it pays more. But there’s still an element of risk involved in accepting the other job, because you can’t really know whether you’ll like it till you try. Furthermore, the only way to find out is to sacrifice your existing job.

Thus, the acceptance of a new job is a hero’s journey. You are the hero of the story and if we ask the question of you, “What are you sacrificing, and what do you think you are getting in return?”, the answer will be that you are sacrificing your existing job, and you are hoping to get a more interesting or better-paying job. The story of your transition into the new job begins with the sacrifice of your existing job and ends when the ramifications of the change are fully worked out and you understand them, i.e., when you fully understand the nature of the sacrifice you made.

What often happens in such cases is that you learn there were things about your old job that you really liked but you weren’t fully conscious of. To quote a Phil Collins lyric, “You don’t know what you’ve got till you lose it.” Put into our terminology, you don’t know what you’ve got until you sacrifice it. This is why the hero’s journey has a lot in common with the grieving process where you have to come to terms with the sacrifice and the fact that it’s gone forever.

In summary, to understand the meaning of any story, we must know what the sacrifice is and why the hero is making it. This is true of an everyday story like getting a new job. It is also true of the greatest stories ever told.

Probably still the most important story in Western culture is the story of Jesus. In this case, the answer to our question, “What is the hero sacrificing, and what do they think they are getting in return?”, has millennia of theological argument behind it. Jesus sacrifices himself, and what he gets in return is the redemption of humanity. We already know the answer, but let’s walk through an analysis of the crucifixion part of the story because it contains some crucial facts that have shaped the tradition of Western literature and theology.

Even if we take a purely secular reading and forget that Jesus is supposed to be the son of God, the crucifixion story still makes clear that Jesus is sacrificing himself. Jesus had gone round making many enemies among the Jewish religious authorities of the time. He had also developed a close relationship with his disciples. If we assume Jesus was a good read of character, it is perfectly possible that he intuited that Judas would betray him to his enemies and that Peter would renounce him afterwards. Even though he knew these things, Jesus did nothing to stop events from proceeding. In that way, he made a decision to sacrifice himself and that forms of the basis of the crucifixion story.

Note also that this is a perfect hero’s journey pattern. Jesus may know what’s going to happen, but we as the readers do not. From our point of view, he is stepping into the unknown. What happens after his arrest is uncertain (even though Jesus has already said he’s going to die).

As most people would know, what actually happens is that the Jewish religious authorities hand Jesus over to Pontius Pilate and demand that he be executed. The crucifixion story, therefore, sets up a dichotomy between the personal sacrifice that Jesus makes and the fact that he is subsequently offered up as a sacrifice by the Jewish authorities.

Here we must note a crucial point about how justice works. The convicted criminal is themselves a sacrifice in the name of the law. In most societies throughout history, the “law” is religious law. Therefore, the criminal is a sacrifice to the gods. But even in a secular reading, the punishment meted out to the criminal is “holy” to the extent that it extinguishes the crime and returns everything to equilibrium. We can see that this process is identical to the hero’s journey and that is why stories involving a crime (or a moral transgression) appear in almost all great literature.

In the case of Jesus, the crime he had committed under Jewish religious law was to proclaim himself the son of God. The priests insist that he be punished (sacrificed) to restore the holy order. That is fair enough. However, the story takes a dramatic twist when the priests hand Jesus over to the Romans to try and have him found guilty under Roman law. They do this because they want Jesus executed, and Roman law forbids execution except by Roman authorities. That is why Jesus is hauled in front of Pontius Pilate with the mob screeching for him to be crucified.

The problem is that Jesus has not committed any offense under Roman law. That’s what Pilate tells the mob. After a few attempts to avoid a wrongful conviction, Pilate literally washes his hands of the affair and sends Jesus off to be crucified.

What that means is the punishment (sacrifice) of Jesus was invalid within the terms of both Jewish and Roman traditions. Jesus was sentenced to Roman punishment even though he had committed no crime in Roman law. Moreover, we can see that both the Jewish priests and the mob were not really concerned with justice but with vengeance. Therefore, they tarnished their own beliefs and their god with a murder.

All of this serves to amplify the dichotomy that the crucifixion story sets up between personal and collective sacrifice. The crucifixion story, perhaps more than any other story at that time or since, makes crystal clear the difference between the personal sacrifice of the hero (Jesus) and the invalid sacrifice to abstract notions of the sacred committed by both the Roman and the Jewish authorities.

This theme of personal sacrifice rightly became a core component of Christian theology and then Western culture more generally. Jesus’ conscious sacrifice of his own life is a symbol that all our lives are sacrifices. Since we all make sacrifices anyway, the only question is whether we do it, like Jesus does, in full consciousness of what we are doing. The crucifixion story is about consciously becoming your own sacrifice and taking full responsibility for it. That’s why it is arguably the ultimate hero’s journey.

The juxtaposition of Jesus against both the mob and the Jewish and Roman authorities also reinforces this meaning. The Jewish priests and the mob do not want to take the responsibility of trying Jesus under Jewish law. They try to fob him off on Pilate. Pilate doesn’t want to take the responsibility either, and he washes his hands of the case. The result is that nobody takes responsibility. The whole thing is a sham. The broader question raised by the crucifixion story is whether any mob or any system of authority can ever really take responsibility or whether in fact such systems are always about avoiding responsibility. If that’s true, then the sacrifice of the individual is always invalid.

In any case, there is only person in the crucifixion story who really takes responsibility, and that is Jesus. The dichotomy is between the lone individual who sacrifices themselves in full consciousness of what they are doing and the baying mob and the authorities who sacrifice other human beings for base motives of which they themselves are not even conscious.

It is sometimes said that all of Western philosophy is just footnotes to Plato. We might make the same claim for Western literature as being footnotes to the crucifixion story. All of the great stories in the Western canon follow the pattern of foregrounding the individual and the sacrifice that they make over and above the societal and collective perspectives. In other words, they’re all hero’s journeys. For that reason, we can begin to understand any classic story in the Western canon by asking the question, “What is the hero sacrificing, and what do they think they are getting in return?”

In relation to stories involving murder (of which Adolescence is theoretically an example), the murder victim is usually the sacrifice. For example, Macbeth is going to sacrifice the life of Duncan. What does he get in return? Well, he gets to become king. Unlike Jesus, however, Macbeth is not fully conscious of what he is doing, and that’s how it is with any hero’s journey where the hero is not God. Thus, the story of Macbeth is largely the story of the competing drives and desires swirling around in Macbeth’s mind, including his revulsion at the idea of murder. Macbeth is only partially conscious of the sacrifice he is making at the start of the story, and it is not until the end that the full horror of what he has done becomes clear to him.

The same applies to the story of Othello, although there is an interesting twist here because Othello is actually the sacrifice and Iago is the protagonist (Shakespeare pulls the same trick in Julius Caesar, where Caesar is the sacrifice and Brutus the hero). In Iago’s case, the sacrifice of Othello is not even made to attain some ulterior goal but simply out of pure resentment at the fact that Othello had overlooked him for promotion. Iago does not challenge his master directly but manipulates others to do his dirty work for him. Eventually, it all spirals out of control, and the final sacrifice includes Desdemona, as well as Iago and his wife.

To take just one more example, the sacrifice that motivates Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment is the murder of the pawnbroker by Raskolnikov. What distinguishes this story is the sophistication of rational argumentation that Raskolnikov employs. As an ex-uni student, he takes a highly intellectual approach to the justification for murder. (Modern uni students still do. See the recent murder of the health insurance CEO in the USA as an example). Dostoevsky’s point is that you can rationalise a murder all you like, but facing its consequences is a completely different matter.

But the Raskolnikov example is valuable for a second reason, because he begins the story by playing the role of the authorities in the story of Jesus. That is, for him, the sacrifice is a purely intellectual exercise in weighing up abstract arguments. The priests in the crucifixion story also had abstract, rational grounds for wanting Jesus punished, i.e., the fact that he had blasphemed. However, they had no grounds for having him killed. Their reason and logic may have been sound, but they had to deceive themselves about their true motives in order to push for crucifixion. That’s how it is for Raskolnikov, too. He has all kinds of ingenious arguments for why he should kill the pawnbroker, but none that actually justify the murder.

This raises another common thread in all the stories we have looked at: the victim is never fully innocent. Therefore, an argument can always be made that they did somehow deserve what they got.

In Othello, Desdemona has kept her marriage to the general secret from her father. This betrayal of familial confidence is what allows Iago to stir up trouble in the first place and sets in train the events which lead to Desdemona’s death. In Macbeth, Duncan seems like a wise and noble king. Yet, he is clearly a bad judge of character who has not seen the unchecked ambition that lies in Macbeth’s heart. Duncan’s lack of judgement and lax security measures bring about his downfall. Meanwhile, in Crime and Punishment, Raskolnikov’s victim is a pawnbroker, a person who profits from the misfortune of others. They are a sinner by default.

Even in the Bible, Jesus is at fault because he really has broken the religious laws of his people. What’s more, he is at fault in a larger sense since he is a god who has manifested in human form. This goes against the entire theological beliefs of the ancients, who saw material manifestation as inherently corrupt. The whole point of being a god was that you didn’t sully yourself in such a way.

Once again, the difference is that Jesus was acting in full consciousness and therefore he fully intends what he does. That’s why we can say that Christianity really did have the effect of redeeming human life in the eyes of the ancients. But that redemption could only come at the end of the story, hence we say, again, that the crucifixion follows the hero’s journey pattern, since the full meaning of Jesus’ sacrifice only becomes clear at the end.

With this rapid overview, we can see some of the main themes that have formed the literary and theological tradition of Western culture, which actually begins before the story of Christ, since we can find some of the same ideas in Greek tragedy. The focus has always been on the hero’s journey, which means the sacrifice made by an individual who must then live through the consequences. The Western tradition has always foregrounded this individual perspective, and this is certainly the main reason why Western culture has always had a far more individualistic disposition compared to other cultures.

The broader point of this tradition is that society can only ever view a murder or a moral transgression from the objective point of view. When the justice system sacrifices the criminal to its abstract notions of the sacred, it must always do so objectively. The law can uphold abstract principles only. More generally, society can only ever sacrifice to such abstractions, whether those be religious and theological (God) or ideological (justice). Society can never take the subjective view in the way that the hero’s journey does. Therefore, full responsibility can only ever attain in the individual.

That is the theological and literary tradition of Western society. All through the medieval period and up until the 19th century, there was a finely tuned balance in Western society with the church as the custodian of the subjective, hero’s journey perspective and the kings of Europe as the custodians of the societal, collective perspective. While the kings were officially servants to the theological tradition, we can say that they implicitly upheld the individualist tenets of the culture.

But all that began to change in the 19th century as the power of the state grew. The state duly used that power to disintermediate the church altogether, and the collectivist mentality took over the culture. That collectivist mentality took different forms, socialism and fascism being the two most notable, but ultimately what was pushed to the side was the traditional foregrounding of individual responsibility as exemplified by the hero’s journey.

And that brings us back to the Netflix series Adolescence, which takes a collectivist approach to what has traditionally been a core subject of theology and literature i.e. murder and moral transgression. After our discussion above, it should not be a surprise to find that Adolescence does this by foregoing the hero’s journey pattern altogether. It is not a story that takes the individual perspective.

If Adolescence was a hero’s journey, it would feature the 13-year-old boy, Jamie, as the protagonist. The story would revolve around the question, “What is the hero sacrificing, and what do they think they are getting in return?” In the same way that Macbeth, Iago, and Raskolnikov have motives for their murders, we would want to know Jamie’s motives. What does he think he’s getting out of it? Is he just out for revenge like Iago? Is he, like Raskolnikov, the over-intellectual incel loner who lashes out through unconscious resentment and shame? Those would be the foundational elements of the story. But any hero’s journey is concerned not just with these facts but also with the way the hero deals with the sacrifice they have made. It is concerned with the consequences to the hero as an individual endowed with a conscience who is capable of redemption. That is what the Western literary tradition would be concerned with.

But the storywriters of Adolescence are not concerned with that at all. To say it again, Adolescence is not a hero’s journey. It is not concerned with Jamie as a subject but with Jamie as the object in a legal proceeding. It is not a question of what Jamie is sacrificing because Jamie is the sacrifice. He is the sacrifice in the same way that Jesus is the sacrifice from the point of view of the authorities in the crucifixion story. Thus, when we say that Adolescence is not a hero’s journey, we can be even more specific and say that it is a story told from the point of view of the collective. That is why it is alternately filtered through the lens of Jamie’s parents, his friends, the police, and the psychologist. The story is concerned with Jamie as object from these various perspectives.

Just as in the crucifixion story, the priests and the mob want to sacrifice Jesus in the name of their abstract notions of the sacred; that is also the sole concern of the storywriters of Adolescence, who manage to insert seemingly all the latest ideological fads into the story. These are the abstract notions of the sacred according to the ideology of modern liberalism. In that ideology, it is the technocrats, the high priests of liberalism, who must find solutions to the various social ills that are preventing the creation of utopia. Jamie is nothing more than the carrier of those social ills, and his sacrifice is meant to appease the liberal gods.

Thus, Adolescence inverts the paradigm of Western theology and literature. It does so by inverting the hero’s journey pattern. It is like telling the story of Jesus’ crucifixion from the point of view of the mob or Pontius Pilate. The only thing that they care about is that Jesus admit his guilt and receive his punishment. And that is really the only thing that the main characters in Adolescence care about. Jamie’s refusal to admit guilt is not a question of personal conscience and a journey towards redemption, such as it would be in a Dostoevsky story; it is a trivial annoyance standing in the way of “justice” being served, such as it is when Pilate gets annoyed that Jesus won’t confess.

That is why we could say that Adolescence belongs more broadly to the age of the Antichrist (both in the Jungian sense and in the sense of being an inversion of the crucifixion story). It’s also why the high priests of liberalism, whether they be in the universities, the public service, or the government itself, are so concerned with problematising the Western canon and “decolonialising” the curriculum in schools. Young men like Jamie might accidentally read Shakespeare or the King James Bible. Hence, Keir Starmer sees it as his number one priority to jam Adolescence down their throats instead.