I have been dabbling with gardening for about ten years or so, but it wasn’t until corona that I got more serious about the food-producing side, and that was mostly because I didn’t have much else to do during the two wonderful years of lockdowns that we got to enjoy here in Melbourne.

Coincidentally, 2020 was about the year that the fruit trees that I planted earlier in my yard were starting to come to maturity and generate decent yields. I then started to expand my vegetable beds. By 2022, I was getting decent enough yields that I decided to start measuring them to see what they were worth.

Now, I wouldn’t say I am active in any gardening forums, but I am a member of a gardening society here in Australia (Diggers club) and I’ve been to a number of permaculture workshops and know people in that space. In addition, I am always looking up gardening-related stuff online. What I realised recently was that I have never seen a single article, blog post, or YouTube video that addresses the question of the monetary value of homegrown food. Because of that, when I calculated my results, I got quite a surprise, which I thought might be worth sharing.

The results I’m about to present were measured in the 2022-23 year. It’s worth mentioning that, although my skills and knowledge had improved by then, I was and still am an intermediate gardener. If what I read online is correct, skilled gardeners are getting about twice the yield I got in 2022-23, especially for things like tomatoes. So, the numbers I am giving are on the low side, especially for the vegetables.

Another thing to bear in mind is that I only measured what made it to the kitchen, and that was less than what actually grew. So, again, the numbers are lower than what they could have been.

These caveats do not affect the overall result; in fact, when corrected for, they make the result even more stark. Let’s look at the numbers. I’ve rounded to the nearest dollar for clarity.

Vegetables:-

| Crop | Yield in $ per m2 |

| Cucumber | $45 |

| Chilli – jalapeno | $32 |

| Tomato – black Russian | $30 |

| Tomato – cherry | $25 |

| Potato | $10 |

| Corn | $7 |

| Carrot | $5 |

| Garlic | $3 |

Fruit and nuts:-

| Crop | Yield $ per m2 |

| Lemon | $10 |

| Pear | $6 |

| Apple | $4 |

| Olive | $3 |

| Almond | $3 |

There are two other results that I had last summer that are worth mentioning here. Both berries and capsicums come in at about $35 per square metre, placing them in the top tier.

These numbers paint a very clear picture: the most valuable things to grow in the garden are summer vegetables, with the humble cucumber sitting as king on the throne! However, I suspect that tomato is probably the real king. This year I expect to get at least a 50% greater yield than I got in the summer of 2023, which would put tomatoes on top.

The real eye-opener from my point of view was the fruit. My olive trees still have some improving to do, but the apples, pears, and lemons are all producing at what should be close to their maximum yield. Despite that, we can see that the value per square metre is low. Trees, of course, take up a lot of space, so this makes sense.

The general rule here seems to be that vegetables are about an order of magnitude more valuable to grow than fruit. This is especially true in my climate, where I have a year-round growing season, and so any square metre of vegetable bed produces both a summer and a winter crop (and potentially even a third crop if I really pushed it).

The lesson from this is very clear: if you are looking to maximise your return on investment, you should grow vegetables first and only bother with fruit if you have space, time, and energy left over. Vegetables have other advantages too. As I mentioned, in my climate, I can grow vegetables all year round, and I can stagger the planting to get essentially a continuous supply as opposed to most types of fruit, which have to be harvested in one big bang.

This raises a fascinating question: why did I have to learn this myself? Why is this message not prevalent, at least in the gardening communities that I have interacted with? I have some ideas why this is the case, but I think the interesting thing is that this lesson was actually present in the original organic gardening movement. That movement distinguished between intensive and extensive crops.

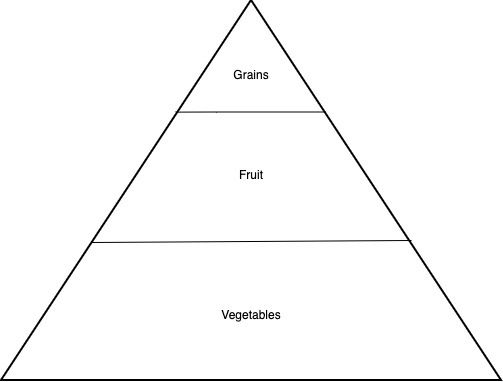

It turns out that my calculations on the value of food exactly map to that intensive-extensive distinction. Vegetables are intensive, and they are distinguished from grain crops, which are extensive. Fruit trees are somewhere in the middle. This gives us a classic pyramid pattern:

For a fixed area of soil, the value of the yield is greatest for vegetables and least for grains, with fruit somewhere in the middle. Thought about another way, to get the same aggregate value from fruit trees requires far more land than for vegetables, while grains require even greater amounts of land. Given that the amount of area under cultivation corresponds to the amount of work required to manage it, less area equals less effort equals more value. Whichever way you cut it, vegetables come out on top.

Intensive vegetable growing allows you to concentrate your efforts. You concentrate your watering, your digging (if you do any), and, most importantly, the organic matter you have available. That’s why composting and mulching are a natural fit for vegetable gardening but become less viable for fruit and grain farming at scale.

There is some interesting work being done these days on using teas to scale the benefits of compost to extensive crops. It would be nice if that turned out to be true. But even if it is true, you’re still doing extensive agriculture, and that means less dollar value per time and money invested.

Now, I mentioned that I had my theories about why the economic angle is excluded from consideration in gardening circles. Let me just give the most grandiose of those.

Most people would know that the Reformation created our modern separation of church and state. Another way to frame that is that it separated economic concerns from spiritual ones. That is actually unusual. If we look back in history, we find that economics, politics, and religion were all mingled together. In fact, temples and churches were often a place of economic exchange.

We have gotten so used to this state of affairs that we tend to think that any pursuit that is not overtly “economic” must exclude economics altogether. Could that be why modern gardening movements like permaculture never talk about money but frame their approach as getting in touch with nature or something similarly spiritual sounding?

The trouble with that, I think, is that I suspect we humans have an inbuilt economic compass. This is also a feeling, very similar to the feeling of being in tune with nature. I think we “feel good” when we do things that have economic value, and we feel bad when we don’t. This was the implication of David Graeber’s concept of bullshit jobs. People who have jobs that they know produce no value suffer anxiety. The opposite is also true; there is an inherent satisfaction to doing something of value.

In fact, I’d say that’s the number one reason to grow food. We live in a society where it is really, really hard to create value since everybody already has too much of everything. Doing something simple and straightforward that creates real value connects back to our economic instincts.