One of the more well-worn books on my bookshelf is Gregory Bateson’s Mind and Nature: a Necessary Unity. As the subtitle of the book suggests, it’s an attempt to unify two domains which we normally think of as separate, sometimes called the mind-body problem.

Part of the appeal of Bateson’s book is that, while it’s full of great insights, it doesn’t really come to an overall point. This leaves the reader to wonder whether they didn’t get it. I imagine some people put the book down in frustration as a result. For others, such as myself, it sends you back to the beginning hoping to crack the code the second time around.

As I mentioned a couple of posts ago, I’ve recently ended up writing my own work of unification as my book project tentatively titled The Age of the Orphan has ended up becoming an integrative theory not dissimilar to Bateson’s. It’s an attempt to account for what seems to me the underlying patterns that unify several domains usually thought to be discrete such as psychology and comparative history.

Thus, when I was leafing through my copy of Mind and Nature about a week ago, I had a new appreciation for the challenges involved in such a work and why Bateson struggled to bring it to a concise logical conclusion. I also saw some correlations with the theory I have been developing. To take one example, Bateson notes in his book that humans think in stories. The underlying structure of a story – the Hero’s Journey – is one of the key elements in my work.

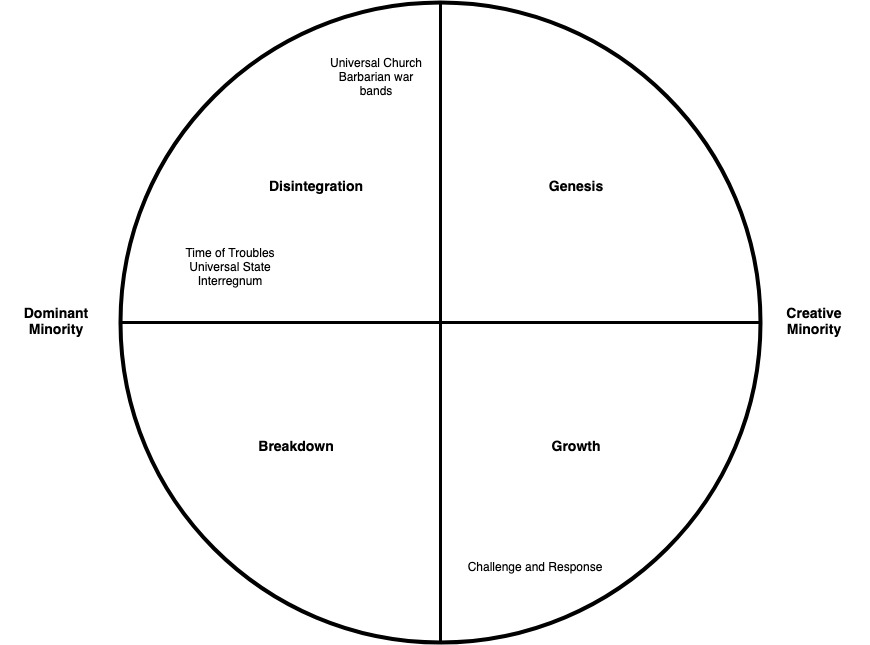

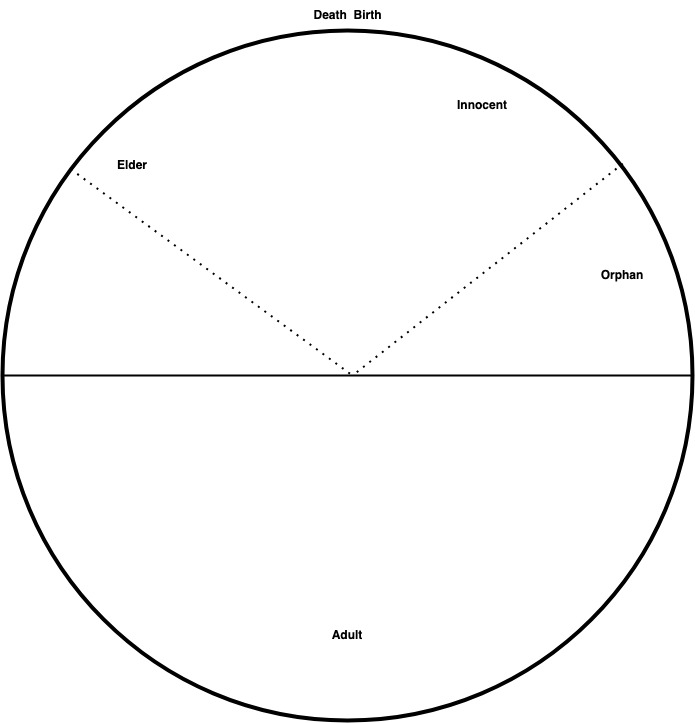

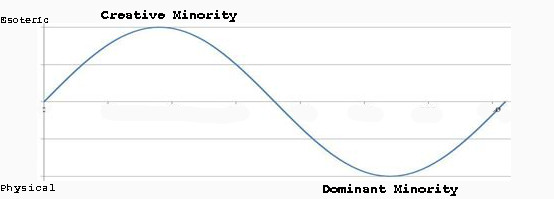

If Bateson is right and mental and evolutionary (natural) processes are identical or derive from the same source, it follows that stories are not just entertaining diversions from “reality”, they tell us something about the nature of reality. That has been the assumption of my work which is that the underlying cyclical structure of Hero’s Journeys is identical with myths, rites of passage, individual lifecycles and the grand arcs of history. We should not think of these as separate but as having an underlying unity. I think Bateson would agree and would also want to include the evolutionary processes of natural history into the theory.

What would such a theory look like? Let’s take an everyday example that is easy to understand to try and elucidate it: the game of tennis.

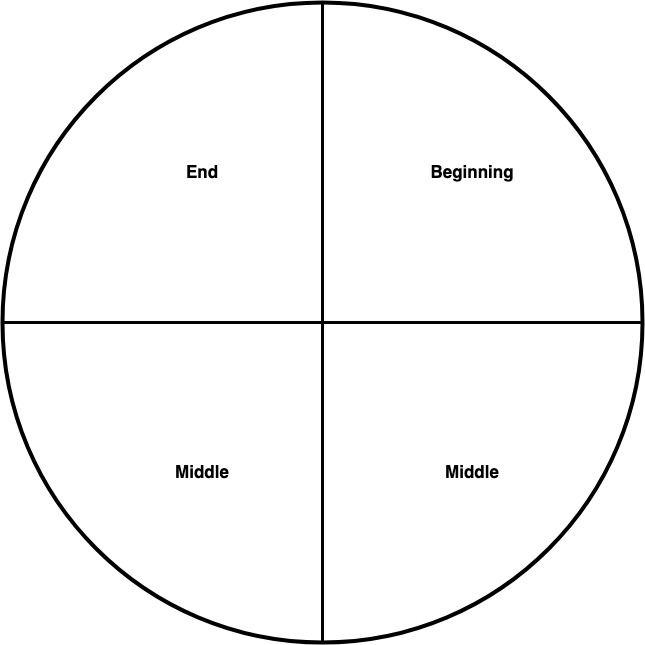

A tennis match can be thought of as a collection of cycles within cycles i.e. a fractal cyclical pattern. A match is made up of sets which are made up of games which are made up of points. Each of these has a beginning, middle and end. Thus, cycles within cycles. We can represent the cycle as follows:

When you get to the end of the cycle, you start again from the beginning. For that reason, we can call each trip around the cycle an iteration. The word iteration comes from the Latin iterare meaning to repeat, to do again. In tennis, there are iterations of points, games, sets and matches.

Repetition is the key to learning and therefore to individual and collective development. Iterations are key to the learning process. But when you iterate on something, you don’t just go round in circles doing the same thing over and over again. Adaptation and learning occurs. Even without any coaching, if you play tennis with some level of enthusiasm, you will get better. You will learn.

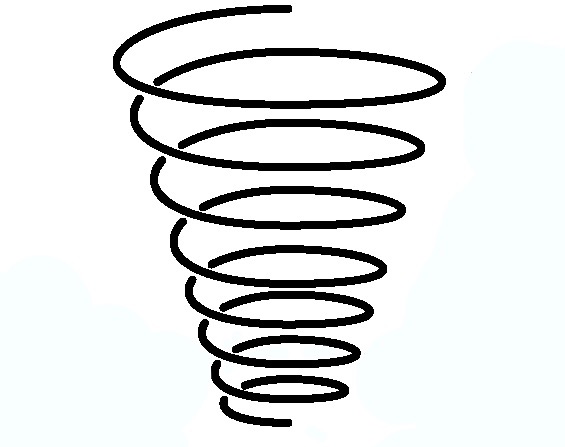

We can represent the learning that occurs via iterations using a spiral:-

The spiral is a series of iterations “on top of” each other. The learning that happens over a set of iterations can be thought of as transcendence. The vertical axis captures this notion of learning as you improve and increase your skill level.

The concept of transcendence was also present in Joseph Campbell’s analysis of the Hero’s Journey. The Hero ventures into the Unconscious, retrieves something and brings it back consciousness. Something has been gained at the end of the process. The same is true of van Gennep’s rites of passage. In our banal example, the tennis player learns something about the game with each iteration.

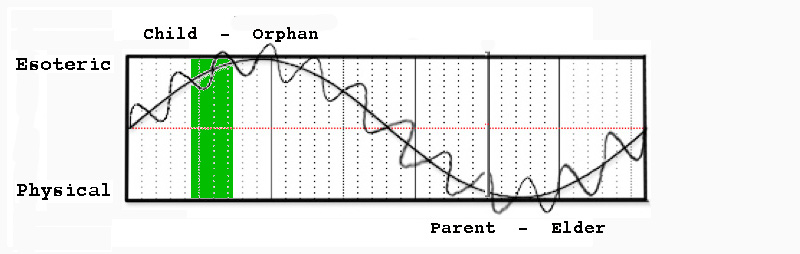

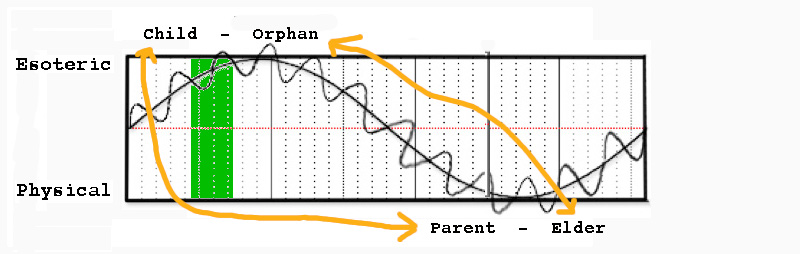

Gregory Bateson noted that what we learn changes over time. As we go through many iterations of tennis matches, Hero’s Journeys and rites of passage, we become experienced and our perception of the world deepens and broadens. We can capture the changing nature of our learning using a diagram of Bateson’s that I have modified as follows:-

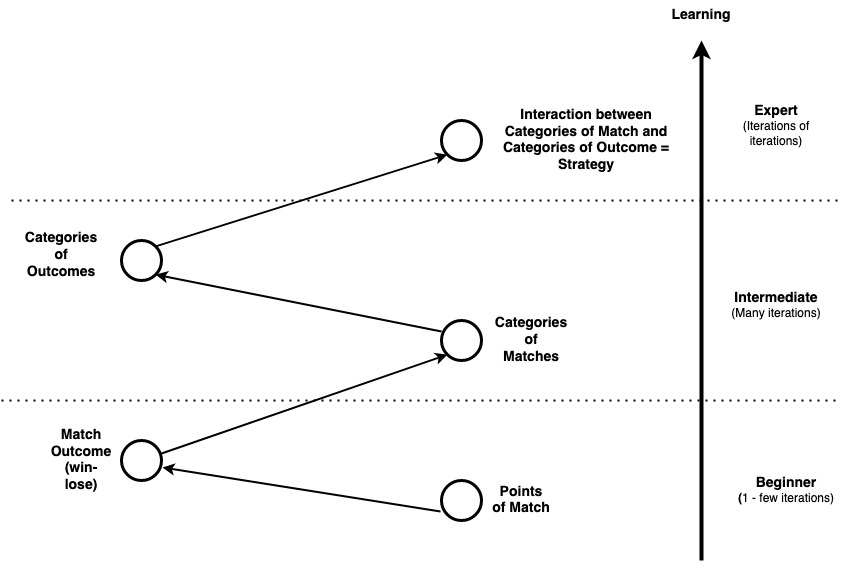

At the bottom level, we have a single iteration of a game of tennis. Many points are played leading to an outcome. Somebody wins. Somebody loses. For the beginner, simply trying to win points by keeping the ball going over the net is enough of a challenge. If you keep iterating by playing games of tennis, that challenge will be overcome and will be replaced by something new. You will start to learn at a higher level of abstraction.

Under the heading of “categories of matches” we include external variables such as the court surface, the weather and your opponents as well as internal variables such as your physical fitness, your technique and your mindset. Over time, you start to pick up patterns. You learn that you play better on hardcourt than on grass. You learn that your backhand is weak and your serve unreliable. You learn that you have a tendency to lose focus in the second set. These lessons are of a different logical type than the simple act of winning or losing individual points, games, sets and matches. We can call this the intermediate level.

If you play iterations of iterations, you might get to expert level. At this point you are able to think about the relationships between categories of matches and categories of outcomes. For example, you are going to play a well-known opponent who always beats you on clay courts. To try and win, you have to come up with a strategy tailored to this opponent on this court surface.

You notice that your opponent has recently been having problems with fitness and so you make a concerted effort to get him running around more than normal by hitting lots of drop shots. You hope this will tire him out and give you the edge in the match. This high level exercise is called strategy.

Although we didn’t represent it in our diagram, there is another level beyond strategy which we might call evolution. If you keep pursuing your strategy of making your opponent run, over time his body will adapt. He will become fitter. Now your strategy of hitting lots of drop shots won’t work anymore because he can run them down. You need to learn to recognise that and modify your strategy as necessary. That is called adaptation.

Over time, you might learn to adapt by hiding your strategy by only using it on important points. Now your strategy includes the concept of adaptation itself. You make an effort not to allow your opponent to adapt to your strategy.

Bateson’s point was that each of these levels of learning is of a different logical type. Over time, our learning itself evolves and adapts towards the higher logical types. Note that the higher levels are predicated on mastery of the lower ones. There’s no point pursuing a strategy of making your opponent play lots of drop shots if you haven’t mastered the technique of hitting a drop shot.

Let’s take this concept of learning at different levels and add another concept I have been using extensively over the last couple of years: the levels of being.

The Physical level of being refers to the material and biological world (note that biology also covers the instinctual and Unconscious aspects of our psychic life). The Exoteric relates to the institutions of human society. The Esoteric relates to the metaphysics of your culture, what is sometimes called the sacred.

We can represent these on our diagram as follows:-

What we are trying to show here is that learning can be thought of as taking place at different logical levels within each level of being.

In the Physical domain, the progression of a tennis player from beginner to expert involves obvious biological adaptations. To become a pro, the player must practice each shot to the point where its execution becomes instinctual. Each sport imposes specific adaptations on the body. For tennis, running and stretching are two of the most important physical attributes needed. At the highest level, strict attention needs to be paid to diet, sleep and rest. Without these, peak performance cannot be maintained. Pizza and beers on a Friday night are a luxury that cannot be afforded.

The development of a player at the Exoteric level of being sees a progression from complete novice at a local club through to local champion, state champion and international superstar. Only about the top hundred players in the world make a living from tennis and so the attainment of the title “tennis professional” is an exclusive club. Meanwhile, the very top players attain a level of fame that is life changing. This implies a significant learning experience since fame and wealth changes your relationship with others and with society in general.

What concepts we include in the category of the Esoteric level of being depends largely on our theological and philosophical assumptions. In the modern West, most people would agree that the Esoteric includes the concept of will (power). In relation to tennis, every now and then a player comes along who has the raw talent and physical capacity to be one of the best but lacks the desire to do so. They lack willpower. Meanwhile, there are other players who don’t have the talent to be the best but manage to keep themselves at the top level through some combination of grit, determination and creativity.

It’s important to realise that, while it makes sense to think of the levels of being as discrete, it’s also true that the overarching process must be synchronous. It’s no use being physically fit enough to compete at the top level of tennis if you don’t also play enough games to qualify for pro tournaments. Similarly, you might have all the (Esoteric) will in the world to be a professional player, but if you’re five foot tall then it’s not going to happen. The laws of physics, the Physical level of being, dictate that.

We have now outlined a model that includes the concepts of logical types of learning arranged vertically across different levels of being shown horizontally. There’s much that could be said about this model but I want to focus on one particular aspect which I think captures something of the difference between the sacred (Esoteric) and the mental (intellect).

Imagine the Wimbledon tennis final. It’s played between two expert-level players. Both players have a coach who is also an expert. The player is an expert experiencing the game from a subjective point of view while the coach is an expert experiencing it objectively.

The match unfolds into a five-set epic. It’s 8-9 and 30-30 in the fifth when Player One misses a crucial backhand down-the-line. The next point he loses the match and the championship.

Let’s say that the coach of Player One has seen his player hit the backhand down-the-line thousands of times and he knows that this particular backhand is one of his player’s weaker shots. Intellectually, the coach might say that this is the decisive moment in the game. He has constructed an explanation for the loss.

Gregory Bateson noted that an explanation consists of a tautology mapped onto a collection of observations. In this case, the observations are all the points of the match. The tautology is: Player One has a weak backhand down the line. Together, these comprise an explanation: Player One lost because of his weak backhand down-the-line.

Note that there an many other plausible explanations. Somebody else might have noticed Player One looked to be getting tired in the fifth set. Their explanation for his loss consists of the tautology – Player One’s fitness level is lacking – onto the events of the match.

Let’s call the construction of such explanations the intellectual-view-of-life.

The player’s perspective on the match comes not from the intellectual realm. A player may go into a match with some kind of plan to play to his opponent’s weaknesses. But by the time you get to the 5th set of a grand slam final, any such plan becomes irrelevant. As Mike Tyson once said, everybody’s got a plan til they get punched in the face. By 8-9 in the 5th set you are just holding on for dear life and relying on instinct and conditioning to get you through the match.

The player’s experience of the match is identical to what Joseph Campbell called the Hero’s Journey and what van Gennep called the rite of passage. It is a journey through the Unconscious and the sacred with all the difficulties and dangers that these presuppose. In other words, the player’s subjective experience of the match is best thought of as a confrontation with the sacred or the Unconscious. It is not an intellectual exercise but a question of the ability to find reserves of strength from one’s entire being. Let’s call this the sacred-view-of-life.

If we stick to the subject of tennis, it’s clear that the intellectual realm plays an important role. It seems almost impossible that anybody today could get to the highest level of the game without professional coaching and training most of which is based on an intellectual approach . The best players pay good money to have a coach there to provide this intellectual perspective so they must find benefit in it.

On the other hand, nothing happens without the Esoteric components of will and the other mental qualities needed to get to play at the highest level. It seems that the intellect and the sacred are two sides of the same coin.

Our model presented above is an explanation and therefore a tautology. There is an assumption in that tautology which is counterintuitive. We saw that learning is built on iterations and each iteration has a beginning, middle and end. Nevertheless, we displayed the line of learning as being indefinite. We might summarise this as “life is an open-ended learning process without discernible limit”.

But this seems to contradict the cyclical understanding that our model presupposes. Many theologies take the cyclical understanding and extend it to cover human life in general. Our lives have a beginning, middle and end. If transcendence is a feature of cycles, isn’t it a property of life itself? In that case, death is not the end but a transcendence. This is not superstitious nonsense. It rests on the same tautology as our model of learning i.e. that there are cycles within cycles and that transcendence occurs at the end of a cycle. If this holds for so many other areas of life, why not life itself?

And if it’s true of an individual life, why not extend it a step further and make it apply to all life. That is what many theologies also do and that leads to the idea of apocalypse. The world itself has a beginning, middle and end. The end of the cycle is a transcendence. Some people go to heaven, some go to hell. Again, this is merely following the same tautology that we have used to explain how learning and development seems to occur in real life.

There is an alternative, but not necessarily contradictory idea, that the highest form of the Esoteric is to throw off the idea of cycles altogether and become one with the perpetual flux off reality. This idea also has a correlation in sports. It’s called being in the zone. Being in the zone does seem to require an expert level of attainment whether it be in sports, religious meditation or other domains.

We can reconcile these two ideas by positing that the learning and development path is cyclical and iterative at the lower levels but becomes progressively less so at the higher. In other words, cycles of learning are a necessary part of training but are themselves a phase to be transcended. Above the cycles comes the ability to face the infinite directly. That is the highest form of the Esoteric.