I mentioned in the last post how the government’s response to the corona event is a prime example of what James C. Scott calls a high modernist, top down, bureaucratic intervention. However, it is also my contention that governments did not want to go down that path. Rather, they were pressured into it by public sentiment that was stoked by the media and the financial interests that use the media to pursue their agenda. Some people have gone down the conspiracy theory route with the corona event and I can see why that seems true. My take is that a system had already been set in place through the WHO and the public bureaucracy. That system necessarily serves certain financial interests given the enormous sums of money involved. When the panic set in, governments were forced to use that system as it was the only game in town.

The fact that the system is a high modernist one is no coincidence because the modern medical and pharma industries are predicated on the naïve germ theory model, a simplified version of the science that is completely out of date with the findings of modern microbiology. High modernist interventions require simplified science because the bureaucratic organisational structure cannot handle complexity. Thus, such interventions will either try to re-shape the world according to the simplified model or simply ignore anything outside that model. The stubborn refusal of governments to allow any criticism of the measures undertaken during the corona event and the wilful exclusion of dissenting voices from the official public discourse are no coincidence. They are part of the pattern of a high modernist intervention.

It is also the case that much of the business model of the modern medical industry is predicated on naïve germ theory. This makes sense for a variety of reasons. One of the main ones is that the germ theory puts the problem outside of you and in the germ while the terrain theory looks for the problem inside of you. If you are sick and you go to a terrain theorist for a diagnosis, they will look for a problem with you. Are you not eating correctly? Are you not exercising? Do you drink too much? Smoke too much? Are you overweight? Are you stressed from too much work? Having found such problems, they will tell you to fix them. You’ll have to exercise. You’ll have to stop eating so much. You’ll have to stop drinking. That’s going to take effort and willpower on your part and this effort and willpower is not trivial. It is easy to see why people would seek a different solution.

The germ theorist doesn’t look for the problem in you. They look for it in the virus or the bacteria. The germ theorist will have a ready-made solution that doesn’t require anything on your part except a trip to the chemist. Of course, sometimes medicine really is the best option, especially for acute illness. However, the modern medical industry now offers a pill even for illnesses such as high blood pressure which are clearly caused by lifestyle and whose obvious solution should be to change that lifestyle rather than take medication.

Another way to look at the difference between the germ theorists and the terrain theorists is that the terrain theorist gives you the power. They’ll tell you that your health is in your hands. With naïve germ theory, the power is in the hands of the doctor and the enormous medical and pharmaceutical industries that stand behind them. Taking care of your own health doesn’t make anybody any money but enormous sums of money are spent on visits to doctors and hospitals. How many of those doctor and hospital trips could be avoided if people were in better health? It’s probably not insubstantial. About 50% of people in our society have a chronic illness and it seems about half of those are related to lifestyle illnesses.

So, there’s an obvious business element to all this. But there is also a moral element to it and it’s this moral element that I want to talk about in this post. The moral element of germ theory involves at least a trust in the medical and pharma industries. But this trust expanded into something more during the corona event.

To my mind, one of the strangest things that happened early on was the spontaneous adulation heaped on the medical profession. In particular, the scenes in Britain were deeply weird. It became the custom at a certain time of day to go out your front door and join your neighbours in applauding the NHS. Doctors and nurses had apparently become the new football players or rock stars. We were told they were heroes.

Interestingly, a kind of hero worship has been part of germ theory right from the start and nowhere more pronounced than in the person of Louis Pasteur. It was not uncommon for Pasteur to also receive applause and standing ovations when he spoke at various conferences. Whatever his scientific merits, there is no doubt Pasteur sought to heighten that fame and adulation.

Antoine Bechamp, his terrain theory rival, did not. As a result, it was Pasteur who was favoured among the political class and was given various assignments funded by the state. This mostly involved going in to solve problems that farmers were having. For example, issues with the grape harvest or problems with disease among livestock. It seems most of Pasteur’s solutions failed and in particular his early attempts at vaccines killed many more animals than they saved. These failures look a lot to me like the failures described by James C. Scott and, indeed, Scott also spoke of the heroic and utopian elements in the high modernist schemes. Here was Pasteur as hero sent in to save the floundering farmers.

With the corona event, it seems that the public wanted a similar heroism.

This desire for heroism wasn’t just limited in the applause for the NHS in Britain. It manifested elsewhere too. Where I live in Melbourne, a mini cult has sprung up around the State premier who has repeatedly taken decisive action including locking down the city on multiple occasions. Nevertheless, I still remember the early days back at the start of March where he, like most political leaders, was accused of dragging his feet. He eventually got the message: the public wanted action. It wanted heroic measures. That’s exactly what he has given them since: firm, decisive action. The fact that the decisions made today are completely at odds with the decisions made a month or two ago doesn’t seem to matter. Consistency is not required. Just decisiveness.

This desire for authorities to intervene might sound so obvious to a modern reader that we forget that it’s still a relatively new thing that really took off after world war two with the massive expansion of the public bureaucracy. Prior to that there was a much more self sufficient ethic among the general public.

In his book, Journal of the Plague Year, Daniel DeFoe (the same guy who wrote Robinson Crusoe) describes the events of 1665 in London during the Great Plague. It is a fascinating read in light of the corona event. In particular, the first quarter of the book is relevant because it details the lead up to the London plague and the response of the public in anticipation of what was to come. That response was stunningly similar to what we saw in the early days of the corona event. With just a little effort to translate the actors of that time into their modern counterparts, you can see that very little has changed in the three and half centuries since Defoe’s day. Of course, back then, the panic was set off by death statistics and not by infection statistics and the geographical area was a London borough rather than a nation state. But the underlying psychology on the part of the public was incredibly similar.

There is, however, at least one striking difference: the people back then expected nothing from the authorities. The King left London at the first sight of trouble. He moved to Oxford and apparently paid no attention whatsoever to the plague or how it affected his people. This was seemingly not a problem among the public who did not expect that his majesty would lift a finger to help them. They had to help themselves. Where the local authorities intervened, the people would simply try and get around those interventions as best they could. In short, there is no heroism nor any expectation of heroism in Defoe’s account.

Of course, back in De Foe’s day there was no public health system and nobody who really could help you. The so-called doctors of the time were mostly quacks and you were better off spending your money trying to get supernatural help which at least didn’t make you any physically sicker than you already were. We, on the other hand, have a sophisticated medical system to come to your aid in the event of illness. The word ‘system’ is the key point here. A system is a collective. A system functions by itself. It is in some sense the opposite of heroism which is about an individual.

In early the days of the corona event, we were told the lockdown measures were in place to protect this system and prevent it from collapsing under a sudden spike in admissions. This was the ‘flatten the curve’ mantra. Politicians initially told us we could flatten the curve by basic measures that wouldn’t require a shutdown of society but there was a revolt against this idea and a demand for tougher and tougher measures. It wasn’t enough to just protect the hospital system. We had to do something more. We needed heroism to save the system.

This example of systems vs heroes is something I have seen in my professional life of building IT systems. Within the parts of IT where I have worked there is an active distrust of the hero mentality because the hero constructs a kind of system where they make themselves indispensable. There are good reasons for companies to not want to have heroes simply because it gives the hero too much power. If you are the only one who knows how a system works you can use that your advantage. It also makes the system that is the company unstable. If something happens to that person the system can grind to a halt.

I remember once sitting in a job interview where the candidate was a hero. He was asked the usual cheesy interview question of what he liked about his job and he said something like waking up in the middle of the night and getting the system back up and running. What he might have said was ‘I like building systems where I don’t have to get up in the middle of the night.’ He wasn’t offered the job. In that company we didn’t want heroes. We wanted system builders.

It’s probably because of this background that I always get a little suspicious when heroics are concerned. No doubt sometimes in life genuine heroics are required. The rest of the time, it seems to me that heroics are a cover for a poorly designed system.

Were our hospital systems poorly designed or, at least, not designed to handle the corona event? Did they need heroes to come and save the day? Obviously this will differ from country to country, but it seems that in most places the answer was a firm ‘no’. Almost everywhere that makeshift hospitals were constructed, they weren’t used. Apart from a couple of hotspots, most places have not seen hospitals overwhelmed. The models used to justify the construction of those makeshift hospitals were not the epidemiological models that I have spoken of earlier in this series. Rather, it was the models of Neil Ferguson and the like. The doomsday models. According to those models we needed action. According to those models, we needed heroism.

We got that heroism in a never before imagined lockdown of society that was supposed to flatten the curve. But that message quickly morphed into something else. It was no longer about saving the hospital system, it was about eliminating the virus and heroic efforts to get a vaccine. I haven’t heard any coherent explanation of why that has to happen. It’s certainly nothing to do with systems anymore. It appears to be pure heroics or pure theatrics. With this we return right back to Louis Pasteur only now he takes the form of Bill Gates. We are told society itself can no longer function as a system without a vaccine. Once again, germ theory and heroism fit together like hand and glove. Once again, we look all set for a high modernist grand plan.

Recall that one of the elements of James C. Scott’s high modernist intervention was that civil society must be made or kept prostrate. I can think of no better way to do that than locking people in their houses. Perhaps the high modernist dreamers saw their opportunity and took it. As society went into lockdown the heroes came out of the woodwork with their grand plans. Perhaps that was always part of the grand plan as the conspiracy theorists would point out. Either way we are now looking at just such a grand intervention. A vaccine for everybody in the world according to Mr Gates.

If a prostrate civil society is required for the enactment of such high modernist plans, one of the more interesting dynamics during the corona event is how civil society became self prostrating. Of course, the army and the police were used to keep people physically in their homes. But there has also been social pressure exerted on dissenters and this pressure took the form of a strange kind of call for anti-heroism. This call focused particularly on quelling dissent around the lockdown itself and also around the wearing of masks.

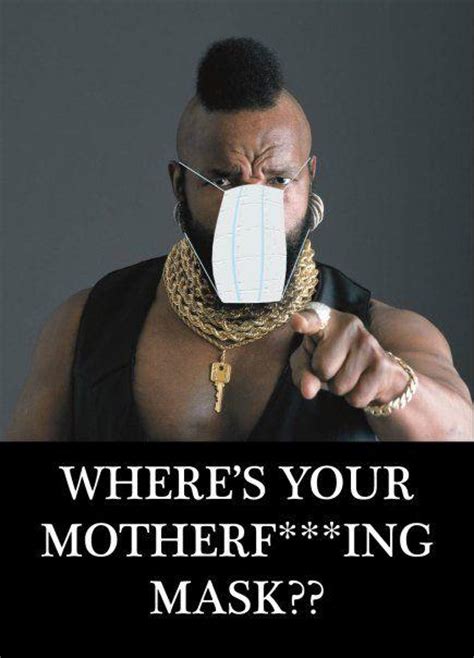

The reader can search the internet for many different examples of the memes that went into circulation. But the common underlying thread in many of those memes was to juxtapose the ‘hero’ against you, the lowly everyday citizen.

Here’s just one of countless examples where Mr T (the hero) puts you in your place courtesy of a bad bit of photoshop.

One of the memes that aimed to quell dissent around staying at home stood out to me. It went along the lines of: “Your grandfather had to fight a war. All you’ve got to do is stay home on the couch and watch television. Think you can handle that?”

Once again, we have the hero (your grandfather at war) and you who are simply asked to do, well, nothing. The irony in this is the fact that so many young soldiers back in the day couldn’t wait to go to war precisely because they wanted to leave home and go and have a heroic adventure.

The underlying message in all these examples is the same. What was required of you during the corona event was precisely not to be a hero. You just had to sit back and let the real heroes do the work. Is it a coincidence that this is exactly the form of the germ theory patient just doing what their doctor says? Is it a coincidence that a terrain theorist would say exactly the opposite: of course, you shouldn’t stay at home. You should go outside and get fresh air and vitamin D and stay active. You should mix with other people and keep your spirits up.

The fact that this clearing out of opposition from civil society apparently took place quite spontaneously via everyday people on social media is just another deeply weird component of the corona event. Just like the people clapping for the NHS in Britain, it seems everyday citizens needed no prompting. They knew the script already. In my opinion, the germ theory has actually become part of our modern collective subconscious. I don’t see any other way to explain the uniformity of action from disparate actors. The germ theory implies a hero doctor and a passive patient. So, we needed the public to play their role and be passive. In the meantime, the real heroes, the real high modernist schemers had moved into position.

At time of writing, we are looking right down the barrel of an epic high modernist ‘heroic’ intervention in our lives. It’s captured in that dreary bit of alliteration ‘the new normal’. Other wannabe heroes have come out of the woodwork with all kinds of ideas of how to re-shape society in accordance with whatever utopian ideal is in their heads. No doubt a lot it is just talk. But with civil society prostrate, now is the time to try your luck. To come back to my heroes vs systems distinction, we are no longer worried about the system. Society as a system now lies helpless on the operating table just waiting for the surgeon’s scalpel. It’s apparently time to operate.

Against the backdrop of this kind of heroism and anti-heroism that has played out during the corona event I would like to give my version of heroism as seen from the vantage point conveyed by this series of posts. The heroes that I see are the ones that have spoken out against the stifling consensus and at least given people some alternative framework by which to understand what has happened. To elucidate this heroism, I’m going to draw on what’s probably my favourite era of film: the film noir of the late 40s and early 50s.

The big, dumb, blunt interventions of James C. Scott’s bureaucrat high modernists remind me a lot of 80s action movies with their big, dumb, muscle-bound heroes running around with bazookas blowing the enemy to smithereens. That works OK in the movies where the bad guys are 100% bad and get exactly what they deserve. It doesn’t work in the real world. In the real world there is ambiguity and complexity. That ambiguity and complexity is far better captured by film noir. Unlike the 80s action hero, the classic film noir hero is a conflicted person with his own inner demons that are exacerbated by the social context in which he or she finds himself.

That hero is often juxtaposed against a rabid mob out to enact ‘justice’. This was a favourite trope of the German director Fritz Lang who had, after all, witnessed that exact dynamic play out as Hitler came to power. Naturally, mobs are not easy to reason with and it’s up to the protagonist to fight back against them.

One of the greatest of the film noirs is the movie Boomerang directed by Elia Kazan. It features exactly this dynamic of a conflicted protagonist trying to neutralise an irrational mob.

In the movie, a callous and cowardly murder has taken place in a small city in America. The townsfolk are horrified and demand the murderer be brought to justice immediately. However, the police have no good leads and results are not forthcoming. Frustration grows and political pressure is exerted on the chief of police to get results quickly. Still no good leads are found but eventually they come across a suspect whose alibi is weak and, although he maintains his innocence, they force a confession out of him.

The case goes to the district attorney who is a handsome, competent and popular man with a beautiful wife and a wonderful life ahead of him. The matter is as straightforward as can be. A suspect has confessed. Everybody in town wants him to be found guilty. All the district attorney has to do is run through the motions. But the district attorney is a man of honour. He checks the evidence and sees that it doesn’t add up. In a dramatic twist he declares that he believes the man innocent at which point he is taken aside by the powers that be and presented with a series of carrots and eventually sticks to get him to do what is wanted. His final choice is clear: he can pursue justice and have his life ruined or he can try the defendant, who will definitely be found guilty, and continue his rise through the ranks of the elite.

The heroism presented in this case is the heroism to pursue what you know to be right even though the society around you will forsake you. Anybody can follow along with what the mob wants especially when it calls you a hero. But the deeper heroism is to do what is right though you will be condemned for it.

The reason why this is specifically relevant in the case of the corona event is because most of the people working in the medical and scientific fields are compromised by the fact that they make their living mostly from government money. Indeed, the corona event has seen a flood of new money go into the biomedical fields. Money for vaccines, the money for the PCR tests, more money for hospitals and all the rest. This gives the people who work in those areas a very strong incentive not to speak out against what is happening. To speak out requires exactly the kind of bravery and heroism presented in the movie Boomerang. It’s to do what is right even though it will hurt your life chances.

One of the surprising and disappointing factors in the corona event has been the failure of the institutions in our society to provide at least one alternative viewpoint on what is happening. In Australia there has been absolutely nothing from opposition political parties, the mainstream media or the scientific and medical establishment. Apparently, we have a complete consensus here on the path forward even though it’s obvious that path forward has changed almost daily and our politicians are making it up as they go. We could barely muster a single dissenting voice that mattered. Lesser voices were of course quickly put down via the usual social media mob mentality that Fritz Lang would recognise.

Fortunately, in this age of the internet we are not restricted by national boundaries and so dissenting voices from other countries are available to us. One particular dissenting voice from overseas captured my attention: Professor Sucharit Bhakti, a professor of medical microbiology and apparently one of the foremost in Germany. Bhakti went public because he saw what was happening made no sense from a scientific point of view let alone a moral point of view. Why Bhakti is even more interesting though is because he was born in Thailand and only recently became a citizen of Germany because he wanted to live in a democracy. Unlike the rest of us who take democracy so much for granted that we are happy to put it on hold, apparently indefinitely, Bhakti reacted with horror as he watched democracy be thrown out the window. The fact that it was done on the pretense of science that didn’t make sense to him was just the icing on the cake.

That is my kind of heroism. The heroism to speak against a stifling consensus. Incidentally, it’s also the job of the true scientist. Where have been the other scientists to speak out? Even Bhakti lamented that his own students (of which there are apparently many thousands) have remained silent. No doubt they are worried for their careers. No doubt many of them are happy to play the role of doctor-as-hero or scientist-as-hero that our society has created for them. But the true scientific hero is the kind of person like Professor Bhakti.

Is it just a coincidence that Germany seems to be one of the few countries where some citizens are protesting against the measures being put in place? At least there they have somebody to give an alternative view based on science.

To return to the movie Boomerang, the district attorney does save the day and he does so in a dramatic gimmick in the courtroom that proves beyond a doubt that the defendant is innocent. Unfortunately, we are not going to get such a certain proof with the corona event. This is the real world and not the movies. There is no smoking gun evidence that is going to change people’s minds. It seems to me that the naive germ theory and the kind of heroism that seems to go with it has now morphed into a high modernist, 80s action movie hero dynamic. Just like an 80s action movie, there’s going to be collateral damage all over the place. The only question at the moment seems to be, how much?

Postscript: the victory of the bourgeoisie

There is one final riff on the hero theme I would like to throw in. It’s related to the modern dynamic between what can broadly be called the romantics and the bourgeoisie that’s been going on western culture for a couple of hundred years. The romantic hero is perhaps best defined by Nietzsche as having a cheerful fatalism. Goethe was Nietzsche’s favourite exemplar: somebody who could accept nature for all it is both the good and the bad. The romantics did not reject nature, they celebrated it in all its power and all its terrifying ambivalence to human life. By contrast, the bourgeoisie was the one who thought they had ‘conquered’ nature but all that had really happened was they removed themselves from it.

When viewed this way, the government mandate to stay at home represents a symbolic victory of the bourgeoisie. Stay home and watch tv. How hard is that? All you’ve got to do is exactly what you’re told.

One imagines the scene from A Clockwork Orange where Alex is hooked up to the Ludovico apparatus and is flashed the hashtags #staythefuckhome and #wearafuckingmask over and over again.

All posts in this series:-

The Coronapocalypse Part 0: Why you shouldn’t listen to a word I say (maybe)

The Coronapocalypse Part 1: The Madness of Crowds in the Age of the Internet

The Coronapocalypse Part 2: An Epidemic of Testing

The Coronapocalypse Part 3: The Panic Principle

The Coronapocalypse Part 4: The Denial of Death

The Coronapocalypse Part 5: Cargo Cult Science

The Coronapocalypse Part 6: The Economics of Pandemic

The Coronapocalypse Part 7: There’s Nothing Novel under the Sun

The Coronapocalypse Part 8: Germ Theory and Its Discontents

The Coronapocalypse Part 9: Heroism in the Time of Corona

The Coronapocalypse Part 10: The Story of Pandemic

The Coronapocalypse Part 11: Beyond Heroic Materialism

The Coronapocalypse Part 12: The End of the Story (or is it?)

The Coronapocalypse Part 13: The Book

The Coronapocalypse Part 14: Automation Ideology

The Coronapocalypse Part 15: The True Believers

The Coronapocalypse Part 16: Dude, where’s my economy?

The Coronapocalypse Part 17: Dropping the c-word (conspiracy)

The Coronapocalypse Part 18: Effects and Side Effects

The Coronapocalypse Part 19: Government and Mass Hysteria

The Coronapocalypse Part 20: The Neverending Story

The Coronapocalypse Part 21: Kafkaesque Much?

The Coronapocalypse Part 22: The Trauma of Bullshit Jobs

The Coronapocalypse Part 23: Acts of Nature

The Coronapocalypse Part 24: The Dangers of Prediction

The Coronapocalypse Part 25: It’s just semantics, mate

The Coronapocalypse Part 26: The Devouring Mother

The Coronapocalypse Part 27: Munchausen by Proxy

The Coronapocalypse Part 28: The Archetypal Mask

The Coronapocalypse Part 29: A Philosophical Interlude

The Coronapocalypse Part 30: The Rebellious Children

The Coronapocalypse Part 31: How Dare You!

The Coronapocalypse Part 32: Book Announcement

The Coronapocalypse Part 33: Everything free except freedom

The Coronapocalypse Part 34: Into the Twilight Zone

The Coronapocalypse Part 35: The Land of the Unfree and the Home of the Safe

The Coronapocalypse Part 36: The Devouring Mother Book Now Available

I think this is actually the most interesting part in your series. While the science is, of course, not at all settled yet, some lessons were clear already at the beginning of March from Chinese publications:

1. Children were rarely diagnosed (combination of flu-like symptoms and PCR test), hardly ever needed intensive care, and hardly ever transmitted the virus to adults.

2. Outdoors contacts hardly ever led to transmission of virus.

3. (From models) A shutdown was useless because infections would rise again afterwards (this is independent of how many cases of disease and death you think would occur from that rise in infections).

So even if you think the virus has a considerable fatality rate at least under some circumstances (which I do, based on Lombardy, NYC and the Amazon, especially Manaus), it never made any sense to close schools and playgrounds, and it never made any sense to ask people to wear masks outside. These policies must be explained by psychology.

Germany has indeed less of a heroic attitude. The policy since May has been to maintain in each township less than 50 new infections per 100 000 inhabitants per week. When numbers rise above that threshold, some restrictions on commerce are re-inacted. I don’t understand efforts to eradicate the virus.

I agree with Matthias that this is the most interesting post in this series. There seems to be no evidence to assume that the virus is anything out of the ordinary. The fascinating thing is our reaction to it, and a lot will be written about that in the years to come.

The fact that there were clearly defined hotspots as mentioned by Matthias seems a case in point for the terrain theory.

although I have some doubt if these hotspots will stand up to closer scrutiny.

@Matthias maybe the eradication strategy can be explained, at least here in Australia, by a perceived failure of politicians during the unprecedented bushfire event just a few months earlier. Of course it is an unreachable goal. Even in a totally clean population, false positives will create a noise floor.

unfortunately this is not even discussed here.